Вы здесь

Nomadic life of Kazakhs in photographs by L. Poltoratskaya.

Photographs by Lidiy Konstantinovna Poltoratskaya

“- Ah! Chumikey! aman (hello)!” the husband shouted, having examined one of the people who had arrived.

Having exchanged Kyrgyz pleasantries, the main one of which was

- “Maljan esen ma!”, that is, “Are your cattle and household healthy?”, the husband told Chumikey that his baibiche (wife) was riding with him.

Then he rode up to me, and put one hand to his chest, and the other, offering me the edge and spreading it out like a fan, he uttered a ton of, I suppose, pleasantries; although I did not understand a word, I answered with aplomb:

- Tar dzhelgasen, Chumikey, tar dzhelgasen (thank you)."

L.K. Poltoratskaya. "A Trip Along the Chinese Border from Altai to Tarbagatai." 1871.

Life of Kazakhs.

One of the first female amateur photographers in Russia, she went down in history as the author of a unique album, “Views and Types of Western Siberia” (1879), which received high recognition in scientific circles. As a companion to her husband, the military governor of the Semipalatinsk region, Major General Vladimir Aleksandrovich Poltoratsky, in the most difficult journeys through little-studied and uninhabited places, she managed to capture the beauty of nature and the life of the inhabitants of Altai and Kazakhstan in the second half of the XIXth century.

Despite these achievements, the main milestones of Poltoratskaya’s biography can be reconstructed mainly from the documents of her father and husband. Even her name was not immediately established: in a number of reference books she is called not Lydia, but Lyubov.

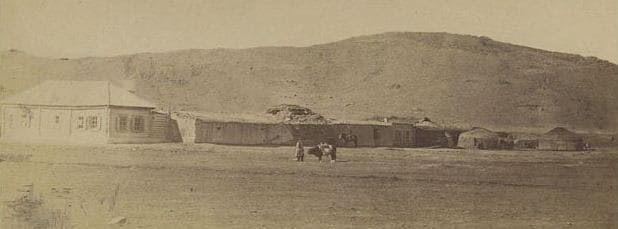

The real name of the wife of the Semipalatinsk governor can be easily found out from the reference books of the 19th century – Address Calendars and Memorial Books. The wife of the Semipalatinsk governor did not like the city itself. This attitude becomes understandable when you see how inexpressive and miserable Semipalatinsk looks in the photo by Lidiya Konstantinovna Poltoratskaya from her album.

The same is evidenced by the description of the city from the explanatory note to the photograph: “Semipalatinsk, consisting mainly of wooden buildings, looks more like a large village. The clothes of the Tatars, Bukharans and Kirghiz (Kazakhs were called Kirghiz or Kirghiz-Kaisaks in the XVIIIth - XIXth centuries. - N.M.); caravans of pack camels, houses covered with turf, and women in veils on the streets give the city an oriental character” (Album of Types and Views, 1879, p. 11).

The impression of an oriental city was reinforced by the view of the main mosque of Semipalatinsk - one of the most beautiful among the few stone buildings in the city. Most information about the views, habits, and interests of Lidiya Konstantinovna can be gleaned from her memoir essays “A Trip Along the Chinese Border from Altai to Tarbagatai” (1871) and “The Bremen Expedition in the Semipalatinsk Region” (1879), which describe her trips with her husband to the south of Western Siberia, including modern Northern Kazakhstan.

Lidiya Konstantinovna was born in the early 1830s to the family of the St. Petersburg writer K. P. Masalsky, the author of historical novels that were popular in his time. He had several children from two marriages, to whom he left virtually nothing as an inheritance.

Nevertheless, Lidiya obviously received a good education. The German scientist and traveler O. Finsch wrote about her and her husband in 1876:

- "The kind hosts spoke German, English and French as fluently as they did Russian" (Finsch, 1882, p. 87).

She was no stranger to literature, as evidenced not only by her travel notes, but also by lines from a randomly preserved fragment of her youthful diary: "I have started writing a story, but I don't know what will come of it." Her husband, Vladimir Aleksandrovich Poltoratsky, was an extraordinary man.

After graduating from the Military Academy with a minor silver medal, he was accepted to serve in the General Staff, where he was in charge of Asian affairs. He was a prolific and successful cartographer. In 1868-1877, Poltoratsky served as the military governor of the border Semipalatinsk region, which was part of the Governor-General of Western Siberia.

During the governorship, the family traveled several times to St. Petersburg and Omsk, the then center of Western Siberia, but more often the trips were to distant districts and outposts. The position of the governor's wife here was somewhat different compared not only to the central provinces of European Russia, but also to ordinary Siberian ones.

The society consisted almost exclusively of military men, educated, there were very few women of any social standing. In 1873 - 1874, V.A. Poltoratsky was in St. Petersburg with his wife, Lidiya Konstantinovna. The spouses undoubtedly witnessed the unprecedented success in the court and scientific circles of the capital of the "Turkestan Album", which the members of the Geographical Society were preparing for display in Paris.

In addition, Poltoratsky was a famous explorer of Turkestan and, for sure, personally knew those scientists, administrative and military officials who took part in the creation of this photo album. The Poltoratskys certainly could not help but notice the increased attention to photography, so characteristic of St. Petersburg at that time, where 110 photographic establishments operated.

The need for photographs that would show with documentary accuracy the landscapes, features of life and everyday life of the various nationalities that inhabited the vast territory of the Russian Empire was growing. The invaluable visual information that photography provided was becoming increasingly relevant for the development of scientific knowledge, enlightenment and education.

The relatively new “photographic” genre was also beginning to play a major role in the development of illustrative periodicals and publishing in Russia. All this prompted L. K. Poltoratskaya, upon her return to Semipalatinsk, to turn to photography, with the help of which she was able to capture and forever immortalize the pristine beauty of Western Siberia.

Poltoratskaya, according to the rules that existed at that time, was the trustee of a girls’ progymnasium and at the same time In 1873 - 1874 V.A. Poltoratsky was in St. Petersburg with his wife, Lidiya Konstantinovna. The couple undoubtedly witnessed the unprecedented success of the "Turkestan Album" in the court and scientific circles of the capital, which the members of the Geographical Society were preparing for display in Paris. In addition, Poltoratsky was a famous explorer of Turkestan and probably personally knew those scientists, administrative and military officials who took part in the creation of this photo album.

The Poltoratsky spouses certainly could not help but notice the increased attention to photography, so characteristic of St. Petersburg at that time, where 110 photographic establishments operated. The need for photographs that would show with documentary accuracy the landscapes, features of life and everyday life of the various nationalities that inhabited the vast territory of the Russian Empire, was growing.

The invaluable visual information that photography provided was becoming increasingly important for the development of scientific knowledge, enlightenment and education. The relatively new “light-painting” genre also began to play a major role in the development of illustrative periodicals and publishing in Russia.

All this prompted L. K. Poltoratskaya to turn to photography upon her return to Semipalatinsk, with the help of which she was able to capture and forever immortalize the pristine beauty of Western Siberia. Poltoratskaya, according to the rules that existed at that time, was a trustee of a girls’ progymnasium and at the same time headed the local ladies’ welfare society for the poor.

The society was engaged not only in providing assistance to the poor, but also in organizing lotteries and amateur performances. This was a common practice. The governor’s wife’s “personal care” of individual families was not entirely common: in particular, 15 families with young children were under her guardianship.

At the same time, she devoted a lot of time and energy to raising her children: a daughter and two sons. The Poltoratsky children often traveled with their parents, experiencing all the difficulties of travel and sometimes being exposed to danger.

The boy in military uniform in the photograph of travelers at Rakhmanovsky warm springs is obviously one of their two sons, Sasha Poltoratsky Like all high-ranking ladies, Poltoratskaya also had to “keep house”, to be a hospitable hostess in any situation.

This is how Finsch wrote about meetings with their family far in the mountains: “Despite the late hour, the general’s wife greeted us with the usual cordiality, and soon we were sitting in a magnificently decorated yurt, having an excellent dinner” (Finsch, 1882, p. 93).

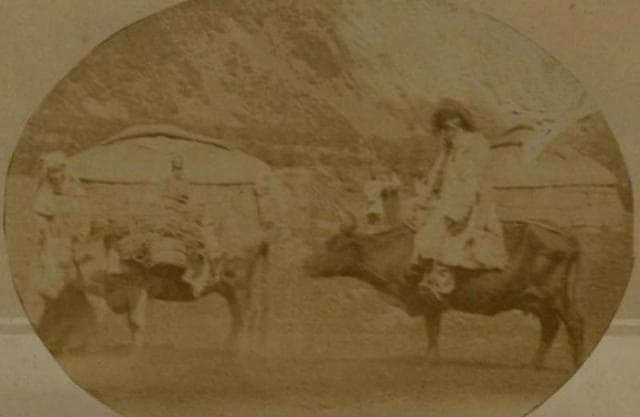

Trips around the region reconciled this Petersburg woman with life on the outskirts, far from the usual European civilization. V. A. Poltoratsky was a famous traveler, and his wife shared this passion. As can be seen from her essays, she rode well and loved this activity. Once Poltoratskaya started racing with a translator:

“There is nothing more exciting than flying across the steppe on a good horse; Kirghiz horses are especially charming in that they themselves get excited about the competition; don’t even touch them with a whip, just shout over their ears, and they see that another horse is passing them, and they fly as fast as they can, they fly so that it takes your breath away, the air whistles in your ears, you feel like you are intoxicated and you want to go even faster, faster, as if wings had grown behind your shoulders, and any minute now, if the horse doesn’t go even faster, it seems like you will throw it and fly yourself! Which is what happens, but only over your head to the ground” (Poltoratskaya, 1871, p. 634). She was equally confident in both a side saddle and a regular saddle, but preferred the latter, as well as a man's suit.

There was no desire to shock in this - it was simply impossible to ride along mountain paths in a side saddle. The traveler was bold and decisive. Finsch, describing an incident on a hunt, directly stated: "Many grabbed their guns, jumped on their horses and, led by the general's wife, as always the most decisive of all, set off in pursuit" (Finsch, 1882, p. 96).

Her own notes recorded many risky adventures and episodes. Here the horses carried the tarantass, and all the passengers fell out of it. Both Lydia and her husband received serious bruises, but they all got back into the same tarantass, harnessed to the same shaft horse, about which they said - "a beauty of a horse!" (Poltoratskaya, 1871, p. 586).

Or another case, when Poltoratskaya and her son risk their lives to cross a mountain river (“I feel the horse swaying under me, bending it like a ring, the water lashing out at my side, so that it reaches my knees, and, most importantly, my soul trembles for Kostya”).

But travelers descend a steep and rocky road, where “after the rain the stones are slippery, there is liquid mud between the stones.” They lose the road at night, but successfully find it: “The coachmen called out to each other and set off further.

Around midnight the moon rose and illuminated the area; huge trees crowded on both sides of the road; in places they thinned out, and a valley opened up on the left, and the mountains darkened on the right... Life had not been as good as it was that night for a long time” (Ibid., pp. 597 – 599).

Participation in travel allowed the hereditary noblewoman, the daughter of a St. Petersburg writer and the wife of a general, to get to know people from a different social environment quite closely. Both her husband and she and the children knew many Kazakh words and tried to observe some customs.

With great sympathy, Lidiya Konstantinovna told how “her husband strongly defended the interests of the exploited or oppressed Kirghiz (Kazakhs) and waged war on the peasants for them, but despite this, the animal-hunting peasants (i.e., those who were primarily engaged in hunting. - N.M.) treated him not only with no hostility, but with respect and true or feigned cordiality ... It seems that they liked that her husband was a hunter and a good marksman himself” (Poltoratskaya, 1879, p. 46).

The children often participated in the trips. The mother was afraid for them, but, obviously, she realized the need for such an upbringing for the boys, the sons of a general. And yet, maternal fear, natural when faced with a real threat, sometimes prevailed.

When she and her son crawled along a mountain scree “on their knees and elbows,” she “didn’t feel any pain from anxiety… the main thing is, like my Kostya.” And having barely climbed out onto solid ground, she thought: “If a few minutes ago, there on the scree, they had sentenced me to be shot for dragging a child into such danger, I would not have uttered a peep” (Ibid., p. 613).

Poltoratskaya’s notes feature many inhabitants of the Russian villages and Kazakh auls that she visited. The real hero of the 1871 essay was an Old Believer peasant from the Bukhtarma village of Belaya. “Barsukov’s appearance is remarkable: unusually tall, lean, broad-shouldered, with large but regular features reminiscent of the faces of the Hermitage caryatids.

Large, dark-gray, intelligent eyes, a black beard with gray hairs and an impossibly tanned face. In her manner, in her speeches, there is calm self-confidence and, at times, humor." Poltoratskaya emphasized many times that Barsukov's fellow countrymen are "a daring, independent and intelligent people," that "their intelligent, free, polite way of speaking is simply amazing" (Poltoratskaya, 1871, pp. 592, 587, 623).

But, probably, "light painting" opened up new expressive possibilities for Poltoratskaya, although it was very difficult to shoot distant views with her small camera, as she herself admitted. However, she had undoubted artistic inclinations, which manifested themselves in the creation of compositions, the choice of photographic points - it is not for nothing that researchers noted how successfully she "took into account the location of individual groups of vegetation and the outlines of mountains, hills, glaciers.

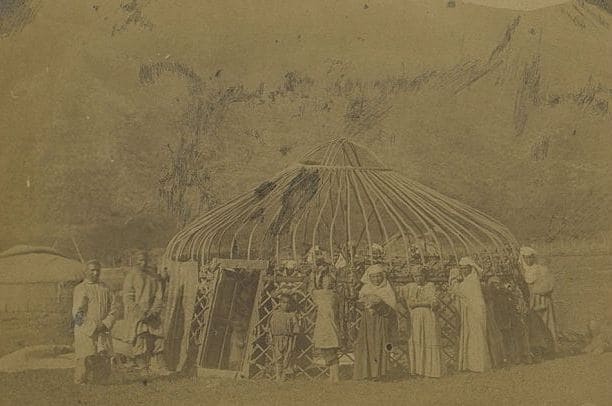

She tried to “raise” the horizon line, which made the picture better filled in” (Morozov, 1961, p. 48). In addition to landscapes (“views”), Poltoratskaya also captured people (“types”) in her series. Such “staged” shots were made not only with skill, but also with an understanding of all the peculiarities of local life.

This is also evidenced by the essays of Lidiya Konstantinovna, in which she sympathetically described the peasants, Cossacks, and Kazakhs she met, and spoke with interest about their lives, everyday life, clothes, and customs. When her husband’s term as military governor ended in 1878, the family returned to the capital. It was then that Poltoratskaya, one of the first female amateur photographers in Russia, was among those who took part in the organization of the new 5th Department “on photography and its application” at the Imperial Russian Technical Society.

This organization became the most important center for the development of photography in Russia for many years. The work of L. K. Poltoratskaya in such an unusual field for a woman of that time received well-deserved public recognition. In 1878, her photographs of the types and views of Western Siberia were exhibited at the Moscow anthropological exhibition, where they were awarded a large silver medal.

Three years later, Lidiya Konstantinovna "presented" her series of photographs of Western Siberia to the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, for which she was awarded another silver medal. The inhabitants of a Kazakh village on the Chinese border were very surprised and amused when Poltoratskaya showed them a glass where they could recognize each other (Poltoratskaya, 1879)/

It should be noted that the history of women's emancipation in Russia is usually associated with the participation of women in the revolutionary movement, with the image of nihilists - take at least their caricatured image in "Fathers and Sons" by I. S. Turgenev. In fact, emancipation affected women from a wide range of social strata, including the upper crust.

And after getting acquainted, even briefly, with the life and work of Lidiya Konstantinovna Poltoratskaya, another image of an emancipated woman of the late 19th century will remain in the memory – a spiritually rich, creative and constructive nature, not afraid of difficulties and always ready to accept something new.

Literature:

Album of types and views of Western Siberia, photographed by L.K. Poltoratskaya. - St. Petersburg, 1879.

Matkhanova N.P., Aleksandrova N.N. First ladies. Siberian province of the XIX century // Science first hand. - 2007. -№ 3. - P.102 - 113.

Morozov S.A. Russian travelers-photographers. - M., 1953.

Morozov S.A. Russian art photography. Essays from the history of photography. 1839 - 1917. - M., 1961.

Poltoratskaya L.K. Trip along the Chinese border from Altai to Tarbagatai // Russian Bulletin. - 1871. - Vol. 93, No. 6. - P.580 - 661.

Poltoratskaya L.K. Bremen expedition in the Semipalatinsk region // Nature and hunting. 1879. – V.1, No. 3.– P. 23 – 52.

Stasov V.V. Photographic and phototype collections of the Imperial Public Library. – SPb., 1885.

Finsch O. Journey to Western Siberia by Doctor O. Finsch and A. Brem. – M., 1882.

The publication uses photographs from the “Album of types and species of Western Siberia taken by L.K. Poltoratskaya” (1879), stored in the prints department of the Russian National Library (St. Petersburg)

The authors and editors thank I.R. Gusalova and E.N. Lopatina (Federal State Institution of Culture “Polytechnic Museum”, Moscow) for their assistance in preparing the illustrative material.

Author:

Matkhanova Natalya Petrovna. Doctor of Historical Sciences, Chief Researcher

Institute of History SB RAS. http://scfh.ru/papers/ee-prevoskhoditelstvo-fotograf/