Вы здесь

Nikolay Zeland about Tash-Rabat in 1886.

Walk along Tash-Rabat gorge.

“A long, long time ago, there lived a certain khan who had two sons. The khan loved his sons equally and recognized them as smart and capable of inheriting the governance of the khanate, but since he did not want to divide his state into two parts, and he did not know which of his sons to give preference to, he decided to test them, for which, having called them to him, he announced to them the following:

- “My children! I love you early and find you worthy of governing the khanate, but I do not want to divide my state, and therefore here is my decision for you: go in different directions, settle among your people and decide what is needed for the well-being and happiness of your subjects.

The sons went their separate ways. Enough time passed. The elder, having come to the conclusion that the power of the state lies in armed force, began to build fortresses on the border of the khanate. He built one near the city of Osh, and the other - the described Tash-Rabat. The younger acted differently. He found that the same could be achieved much better by developing agriculture, trade and industry, improving the life of his subjects and spreading literacy among them. By his actions he earned the love of his people; and at the same time he inherited the khan's throne.

A. Voitsekovich. "About Tash-Rabat." S. Ya. Peregudova. "Tash-Rabat." Frunze, 1989.

Tash-Rabat caravanserai in Kyrgyzstan.

"In the Tash-Rabat gorge (or valley) it was necessary to make a day's rest, partly to give the animals time to gather strength for the upcoming climb, and partly so that they themselves could get used to the rarity of the air. The gorge itself lies at least at 11,000 feet.

The valley has a desolate, sad appearance. On all three sides it is surrounded by mountains, partly covered with scanty yellowed grass, and on the hills strewn with snow. The day here is significantly shortened by the obscuring mountain fence, which cools the air even faster.

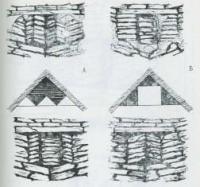

On September 9th at midday it was 12° R. in the sun, frost at night. It was impossible to find a more suitable place for the archaeological rarity that turned up in this valley and which I will now describe. In the closed corner of the triangle you will see an unusual-looking gray stone building. It is a quadrangle with a flat top, in the middle of which sits, like a cap, a rough, half-collapsed dome.

The interior of the building is entered by a single, rather high arched entrance, there are no windows. The entrance opening is the beginning of a corridor, which in the middle part of the building widens somewhat, crossing with another shorter one, i.e. in the center something like (23) a hall is formed, which is under a dome.

From it, vaulted corridors go in four directions. From the front, i.e. entrance, in one direction there are still side, narrower corridors. Both in the main and in the side corridors, openings 1-1½ arshins high are noticeable in the wall, which lead to blind cells.

The cells are quadrangular at the bottom, round at the top, the vault of some has collapsed, while those in which it has been preserved are absolutely dark. Their volume, judging by the eye and measuring in steps, is no more than 1 cubic fathom.

You have to bend down a lot to enter them, and in some you have to crawl. Their interior is completely bare, there is no trace of fireplaces, bunks, niches, etc. The entire building is made of irregular pieces of blue and reddish slate, which is abundant in the surrounding area, joined with cement. In the middle hall, here and there, pieces of rough plaster have been preserved, but there are currently no images, such as bas-reliefs, inscriptions, etc.

But I hasten to add what was conveyed to me by Lieutenant Colonel Volkov, who saw this building in 1871, i.e. 15 years before me: at that time, rough figures of a three-headed horse and a five-headed dragon could be made out on the plaster. It must be assumed that the plaster with these images has since fallen off.

Now one can see only some Arabic inscriptions, apparently made by Muslim travelers from some caravans, who in bad weather put their horses under the arches of this ruin. The length of the entire building is about 48 paces, the width is 36, the height of the dome is 12 arshins, the height of the main corridor is about 4. Who built this building and what was its purpose?

It could not have been a fortress or a private home. Even less a prison - who would need a prison in such a remote and inconvenient place? Moreover, the arrangement of the cells is not like that of prisons, for example, there are no traces of the attachment of locks, (24) chains, etc.

Most likely, in such a place one could assume a house built for the shelter of caravans, which, indeed, have been traveling this way for a very long time. But its physiognomy is completely unique, not at all similar to the caravanserais and rabats built for this purpose.

Who would have thought of spending so much extra material to make the entrance to individual cells so inaccessible and completely isolate them from the light? Even now, caravans take shelter in the middle large room in bad weather, but no one even thinks of using the individual scattered holes.

The individual rooms of the caravanserai are usually arranged in a row, directly from the courtyard or entryway, and are not hidden in the windings of narrow and dark passages. If a larger number of individual rooms for travelers were needed, which, incidentally, is also not the custom among uncultured peoples and with the caravan method of travel, then it would have been possible to use the extra material to increase the outer wall and arrange the cells along the courtyard or entryway, which would have been incomparably more convenient and simpler.

It is most likely that this was a kind of monastery, which, at the same time, provided assistance and shelter (in the middle rampart) to travelers, but what kind of monastery could this be? The hermitage-like form of the main corridors suggests Christians. There is, indeed, reason to assume the existence of Christian monasteries in Semirechye in the Middle Ages.

For example, one of the inscriptions of the recently discovered Nestorian cemetery near the city of Pishpek reads: "This is the grave of Shelikh, the famous exegete and preacher, who enlightened all the monasteries with light." The years of death in the inscriptions that have been analyzed so far range from the middle of the IXth to the XIVth century.

The oldest graves of this cemetery are deeper than the newer ones. On the other hand, it is known that Buddhism flourished in Kashgaria at the beginning of the Middle Ages, which fought Islam for a long time and, (25) probably managed to spread to the north along the same routes that Christianity took, carried by Nestorian missionaries.

Perhaps the fantastic animals mentioned above are more of a hint at Buddhism, although it should be remembered that in these remote regions even Christians sometimes made concessions to local ideas and customs. But in any case, it must be assumed that if this house served as a permanent residence for some people who had dedicated themselves to serving God and their neighbors, then such monasteries were probably few in the world.

There were many hermits who lived in caves, but this usually happened in southern countries, where such a roof could only provide a pleasant coolness, and in a cave directly facing the light of God, there could still be enough light. But here, where the climate is, one might say, polar, where there is no fuel, and I do not see any devices for heating, and any other way of making a fire should.

And the deprivation of light? Let us suppose that if these were cells, then lamps were burning in them, and such an obviously deliberate exclusion of daylight was probably instituted for the purpose of greater solemnity and concentration. But, nevertheless, the very accustoming oneself to such a miserable surrogate for the sun's rays must have cost a person something.

And to this there is the separation from people, the sad locality and the exclusion of the most necessary household appliances, for there is not even anything resembling kitchens, storerooms, etc. The life of a Kirghiz in a yurt, in (26) the cold season and in bad weather, when it is necessary to close its dome and lower the door felt, is also not particularly attractive, but still it cannot be compared to life in these stone coffins.

In general, it can be assumed that if there ever were members of some community here, they were people of strong will, especially since they had to live in great poverty, otherwise the very existence of such a defenseless monastery in the mountains, which had long been the residence of predatory nomadic tribes, could not have been possible.

If there were Christians here, then, of course, the monks belonged to the same Nestorian branch of Christian teaching that spread throughout this region in the early Middle Ages, and were in contact with the Nestorian Christians of Samarkand, Kashgar, Merv, Herat, Khanbalik (Beijing), etc.; all these metropolises are mentioned in one surviving Nestorian manuscript of the IXth century.

It is difficult to say to what century this building should be attributed, about the very nature and origin of which the local nomads have preserved the most contradictory and implausible legends. But it breathes something very distant, and at least there is no doubt that this gloomy abode, hidden in a forgotten gorge of the Asian Alps, stands before us as a silent messenger of hoary times.

Here on the heights of the Tien-Shan, the desert is as it was, that is, it continues to be contemporary with that distant era when the Nestorian missionaries brought the torch of teaching to the Turkic barbarians. And in the valleys of

Semirechye, only before our eyes did a new spirit begin to blow, and since the time of the Nestorians they have slept the half-sleep of primitive forms of life.

And if we look to the West - what an infinitely long string of events and accomplished destinies passes us by during this long millennium! (27) When the first graves were dug in that cemetery, which in our days has again seen the light of God, in Russia they were just beginning to think about calling in the Varangians; the nascent France and Germany; the papacy, which before our eyes had surrendered its thousand-year-old secular power, was only just beginning to consolidate itself in it, and Gregory VII's grandfather was probably not yet born; Venice had only just taken root on the island of Rialto; the Norwegian Gunbjorn, the distant predecessor of Columbus, was discovering the coast of Greenland, and the Norman swans were still sailing along the shores of Europe, looking out for places to found kingdoms that had now long since crumbled!

I regretted very much that I could not examine the crypt in the monastery, the tombs and bones of which would probably have given some information about the character and history of this building. The Kirghiz, who led me along the roof, or rather along the outer, more or less low surface of the ceiling of this building, showed me the location of the crypt, and assured me that "Sarts and Kirghiz" were buried there.

Systematic archaeological research remains to lift this curtain.

Comments.

23. Its berries are edible.

24. Marco Polo, for example, only praised the gardens and vineyards, but was completely silent about the buildings or any remarkable structures. (Ritter's Geosciences. East and Turkestan).

25. In addition to pilaf and pelmeni, shurpa and mullet are prepared, the first is a mutton soup with herbs, the second is chopped meat with vermicelli.

26. The longest average was 18.02, the largest diameter 15.67.

27. It is remarkable that there are almost no Jews in Kashgar. The Sarts, whom I asked about the reasons for this phenomenon, answered that they did not know, but added with a smile: "and it is good - that there are none." Before my arrival

n Kashgar there were two Jews, but they also emigrated to Russia.

Authority:

N. L. Zeland. "Kashgaria and the passes of Tien Shan". Travel notes. Notes of the West Siberian Department of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. Book IX. 1888.