Вы здесь

Nikolai Konshin about Karkaralynsk.

Sightseeing tours in vicinity of Karkaralynsk.

"The only merit of this town is its surrounding nature. Amidst the boundless steppe, a small black ridge has formed, where, despite the black cliffs, curly pines grow, and clear lakes lie in the small valleys. One lake even lies at the top of a high mountain, and since time immemorial, the Kyrgyz have known it as Shaitan-kul, meaning 'Devil's Lake.'"

G.D. Grebenshchikov. "Karkaralyn Philistine." 1916.

Karkaralynsk architectural landmarks.

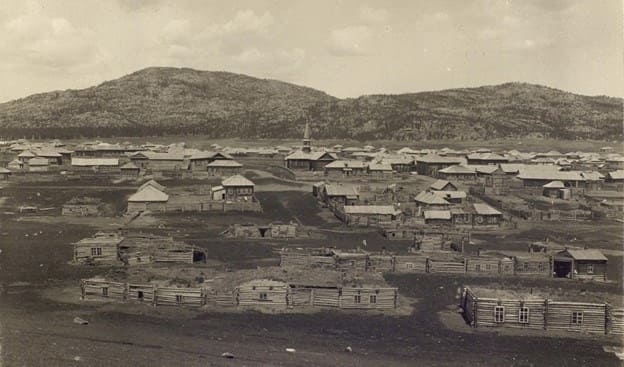

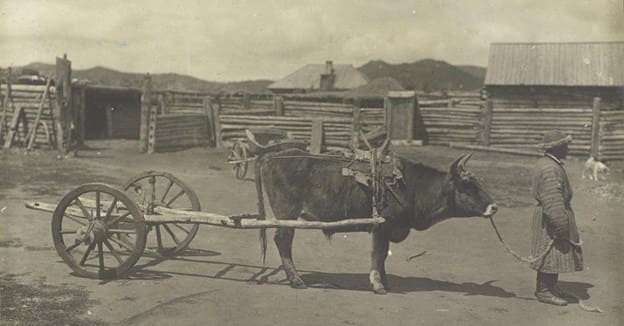

The town of Karkaralynsk is located at the foot of the Karkaralynsk mountain range, in a lowland surrounded by mountains to the north, west, and south. According to official data for 1899, Karkaralinsk, including the Karkaralinsk Cossack stanitsa, had a population of 3,474 villages, including 531 Cossacks, 472 Tatars, 1,912 Kyrgyz, and 559 others.

The town is divided into three parts: the central part, where the church, the city garden, and the large district administration building are located; the stanitsa with the narrow mountain river Karkaralinka; and the Tatar part. In early June of this year, Karkaralinsk suffered a massive fire: the entire stanitsa and many buildings in the central part of the town burned down, so I could only judge the extent of the fire by the surviving Tatar part, with its fine wooden houses and wide streets. They say that many local industrialists and officials had very fine houses in the stanitsa, and overall, it was well-maintained.

The fire broke out during the day, during such a strong wind that saving anything was impossible. Furthermore, there was nothing to put it out with: the Karkaralinka River had dried up so much from the drought that the things transported from the fire to its riverbed burned.

To top it all off, most of the residents of Karkaralinka were in Kuyandy at the fair on the day of the fire. In my time, the fire victims were sheltering wherever they could find them: in the houses and barns of friends, in yurts, and even in government buildings.

The Cossacks were given generous allowances by the army, but the situation for the rest of the fire victims, especially the poor, was dire. As I said, in the central part of the city is the city garden. It's small and wouldn't be of any interest to a tourist were it not for a very original monument.

When I was told about it, I couldn't even begin to imagine which great man from Karkaralinka had been honored by his fellow citizens with such a publicly funded monument. The district officials in Karkaraly were all meek men, and none of the ordinary citizens made any discoveries or demonstrated any remarkable feats.

There was one prominent miner in Karkaraly, whose fame spread far and wide throughout the Semipalatinsk region, but he, too, was more famous for his "generous Russian nature." As I was told, the town was solemnly celebrating the day of the Baptism of Rus'.

One of the townspeople delivered a speech, and the touched citizens decided to commemorate the event by erecting a monument in Karkaraly. The inevitable A. I. Derov donated the money, the monument was commissioned, and finally it was ready, but then the thorny question of where to place it arose.

Opinions were divided, several hostile "parties" formed, and the monument ended up in the district administration archives, from where it was retrieved several years later by the current district governor. Upon assuming his post, he accepted the original archival file "On the Monument with Its Appendix."

The file, as expected, bore the inscription:

- "Consider this matter closed and promptly submit it to the archive," and then:

- "This matter, along with the monument, has been submitted to the archive."

The ill-fated monument was removed and ceremoniously erected in the city garden. The monument is small, in the form of a cast-iron cross on a granite pedestal. The inscription reads: "July 15, 1888, from the Orthodox residents of Karkaraly in memory of the baptism of Rus' in 988."

There are no "societies," not even a club, in Karkaraly, and visitors likely find life there very difficult. A small public library, founded in 1892 - 1893 on the initiative of the official V.N. Markov and with the active participation of engineer Bastrygin, unfortunately almost entirely burned down that summer.

Recently, the question of organizing public readings was raised. A. I. Derov donated 300 rubles to this endeavor, and a special commission was formed to develop a plan for the readings, but that was the end of it. Karkaralinsk has three educational institutions: a primary agricultural school, a three-year city school, and a girls' parish school.

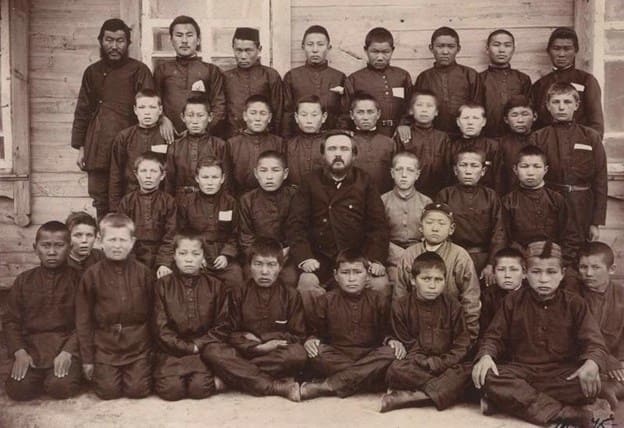

The latter two exude a sense of neglect; their buildings are poor and so cold that, according to teachers, the temperature in winter drops to 0 degrees. Last year, of the 120 students in the city school, 76 were Russian, 36 were Kyrgyz, and 8 were Tatar.

According to the school inspector, Kyrgyz students have a very difficult time learning due to their complete unfamiliarity with the Russian language. To help matters, the teachers themselves are sometimes forced to communicate with the boys, initially, in Kyrgyz.

Generally, as far as I know, among the Kyrgyz, under more or less favorable conditions, there is a noticeable desire for education, and by all accounts, they not only don't shy away from Russian schools, but actually prefer them to Tatar Muslim schools.

The Karkaraly City School educates children of both local Jatak and steppe Kyrgyz, mostly middle-income families. There is no stipend at the school, and poor Kyrgyz, like everyone else, are exempt only from tuition fees. According to the inspector, both children and parents hold the school in high regard and value it very highly.

Upon completion of the course, many become volost clerks or work in Karkaraly state institutions as scribes, translators, and so on. The lack of a boarding school for the steppe Kirghiz was pointed out to me as a dark side to the schoolchildren's lives.

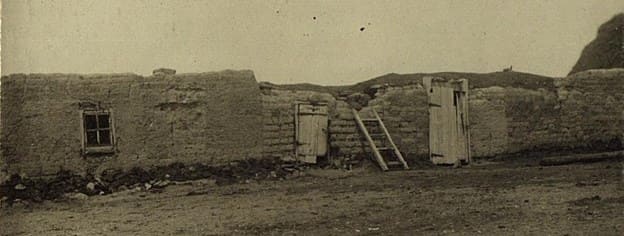

Outside of school, they huddle, almost unsupervised, in Jatak huts, often in very unsightly surroundings. Karkaraly District has long been renowned for its mineral wealth: silver, lead, copper, iron, coal, and other minerals have been found in various places. Just as in Pavlodar District, mining was concentrated in the hands of A. I. Derov, so in Karkaraly District, until recently, the most important miner was S. A. Popov, who died in 1895.

Now Popov's mining business has been seriously undermined, and his heirs, as I've been told, are seeking foreigners, high and low, to buy or lease all their factories, mines, and claims. Popov's heirs aren't the only ones dreaming of the arrival of "Vikings" from overseas, however: other residents of Karkaraly have placed numerous claims in the hopes of those same foreign buyers.

A kind of speculation is beginning to develop. Some agents of foreign entrepreneurs do indeed come to Karkaraly from time to time, inspect the ores, and take stock, but for now, that's all there is to it. S. A. Popov established two factories for smelting copper, silver, and lead: Stepanovsky, in 350.

From Karkaralynsk, at the Kyzyl-Aspe valley, where rich silver ores were discovered, and Kozmodemyanovsky, 24 versts from the city, at the Dzhangyz-Karagay valley. The latter plant primarily smelts copper. In 1899, both plants smelted ore and produced approximately 85 poods of silver, 10,734 poods of lead, and 3,914 poods of copper.

One of the main reasons for Popov's poor state of affairs must, of course, be acknowledged that, until recently, these affairs were managed by people with very little understanding of the mining industry. For example, the managers included a retired assistant district governor, and even a telegraph operator who had ended up in Karkaralynsk by chance.

Everything was done without a strictly defined program, without knowledge, almost on the basis of the Russian "maybe." But in the end, it didn't work out... Meanwhile, judging by the literature, the ore wealth in the Karkaraly district is so vast that its development, despite various unfavorable conditions such as the absence of not only railways but also navigable rivers in the region, should have yielded great profits.

I visited one of the factories, the Kozmodemyanovsky, and I think anyone who saw the old factory buildings would have concluded that business here is definitely not developing... They say the copper at the factory melts so well that it could easily be smelted from waste alone. And as a result, say what you will, we can't do without "Varangians" anywhere...

Authority and photographs by:

N. Ya. Konshin. "From Pavlodar to Karkaraly." Travel sketches. A commemorative book of the Semipalatinsk region for 1901. Semipalatinsk, 1901.

https://rus-turk.livejournal.com/749123.html