Вы здесь

Early medieval cults.

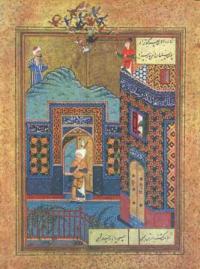

Photos of Samarkand and its history.

“That was the day the ancient songs of blood and war spilled from a hole in the sky

And there was a long moment as we listened and fell silent in our grief and then one by one, we stood tall and came together and began to sing of life and love and all that is good and true

And I will never forget that day when the ancient songs died because there was no one in the world to sing them”

Brian Andreas.

Uzbekistan and the New Silk Road.

In the pre-Arabic period, religious and cultic environment in Central Asia represented a motley picture of beliefs – Zoroastrianism, Nestorian Christianity, Buddhism and Manichaeism. Royal dynasties patronized Zoroastrianism, which prevailed.

For its millennial history, this religion had absorbed a plenty of local cults, including cults of fire, water, earth and air. Zoroastrianism esteemed archaic Indo-Iranian gods and ancestor worship. Fire became a major cultic symbol.

Zoroastrians considered that, on the last day of life, everybody is given his own by fire of Ahura-Mazda - “heavenly lord”, fighting against forces of evil. Alongside with Ahura-Mazda, Zoroastrian pantheon included solar (male) deity Mithra, a patron of warriors herds, and lunar (female) deity Anahita, a patroness of farming, a goddess of war and victory.

In the Early Middle Ages, Central Asian Zoroastrianism was influenced by Sassanian Iran, where it was the official religion.

However, local Zoroastrianism did not follow strict canons, and its cultic traditions had a rich variety. For example, in Sogd, Bukhara and Khorezm, the important role belonged to the cult of Siyavush, having features of dying and reviving deity and recognized as a patron of royal dynasties.

In cities and villages of Central Asia were built Zoroastrian temples and sanctuaries with wooden and metal idols or with wall paintings, exposing this or that deity. Typical were temples of fire in a form of chortak - square dome pavilions with arches on four pylons and sacred fire in the center.

Zoroastrian funeral rite had own specific features. Flesh was naturally removed from bones of the dead in special buildings – nauses. After that, the bones were put in ceramic vessels, and later - in ceramic ossuaries.

In the IIIrd century B.C. and later, ossuaries were made in a form of hollow statues - sitting figures, horsemen as well as tower-shaped ossuaries, imitating mausoleums. From the IIIrd century A.D., ossuaries of different forms came into use: sarcophagus-shaped, vaulted and rectangular with figurines of birds and four-pitched roof.

In the Samarkand Museum of History and Art there are some ossuaries having refined decoration. From the second half of the VIIh century, Samarkand as well as the other Sogdian principalities had to defend their lands from permanent invasions of Arabian troops.

At the beginning of the 8th century, Qutaiba ibn Muslim conquered Tokharistan, Khorezm and in 712 besieged Samarkand. The Arabs set 300 battering rams around the city. Ihshid Gurek bent to the Arabs and recognized dependence on Caliph.

He pledged to pay 2 million dirhems and to give three thousand slaves. Gurek gave the central part of the city to the Muslims, where Qutaiba built a mosque and installed minbar. When, on demand of Qutaiba, the citizens dismantled the central temple, the wooden idols formed a mount equal to the temple in height, as the Arabs witnessed.

For next two centuries, Islam had become a dominant religion in Central Asia, though Zoroastrian communities still existed in Khorezm and Sogd down to the Xth century.

Authority:

Alexey Arapov. Samarkand. Masterpieces of Central Asia. Tashkent, Sanat. 2004.