Вы здесь

Falling minaret of Ulugbek Madrasah.

Leisure package tour on Registan.

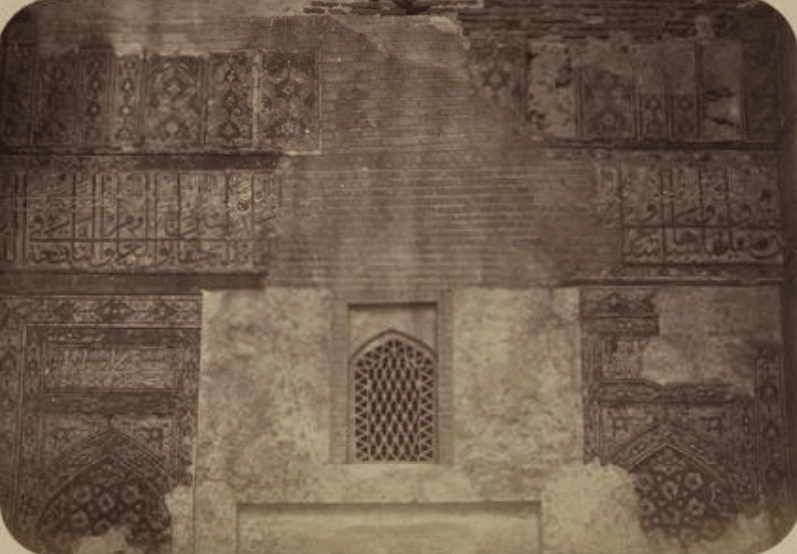

“One can say about this house: it is a multilateral illumination for people, a straight path, a mercy for people who have the right vision. The worthy sultan, the son of the sultan, the founder of this building of science and beneficence, the supporter of peace and faith is Ulugbek Gurgan. May Allah keep the palace of his rule, strengthen his foundation until the end of his state's existence. Truly live well in this magnificent madrasa: Peace to you! You were kind, for then enter into it, remaining in it forever. Year 820. Let it be known: this building is the most excellent and highest of places in the world, the most perfect of buildings in art and work, it indicates the fundamentals of science and guides the way of salvation; the people of Shari'ah and fatwas living in it; therefore this great school is called “the scientists live in it”

Growing magnet for travellers in Samarkand.

During the reign of Timur's grandson - Mohammed Taragai Ulugbek, the first building of the complex, the Ulugbek Madrasa (1417-1420), was built on the Registan. The construction was carried out by order of the ruler and scientist himself - it was in the first half of the XVth century due to the construction of this madrasah and observatory in Samarkand, the city is gaining popularity as one of the main centers of science of the medieval East.

The history did not preserve the name of the architect of this structure, however, the message of the Herata poet Zainutdin Vasif, 40 years old who lived in Tashkent, is known, that he was one of the students of Kaza-zade Rumi - Kamaladdin Muhandis.

Ulugbek Madrasah is a closed rectangular courtyard, the back side of which was occupied by the mosque’s audience. At the corners of the ensemble rose 4 minarets. Around the courtyard were two tiers of open arches, beyond which were located fifty cells, and in which more than one hundred students enrolled in madrasas.

Along the axes of the yard are deep niches. Originally, the Ulugbek madrasah was a two-story building with four domes above the corner auditoriums. The square of the madrasah is drawn by a gigantic portal occupying two thirds of the main facade, and a high deep pointed arch.

Three more of the same portal, but smaller, located on the other three sides of the building. The rear portal served as the entrance to the mosque. Portals are the most remarkable elements of the building, they have a purely decorative function, their meaning is only in the impression of monumentality and grandeur.

This impression is achieved by a very simple technique - exaggeratedly large door niches. With all its monumentality, the building gives the impression of lightness and grace. Embossed details of the walls, talking about their weight and thickness, or completely absent, or minimized.

The intricate decorative geometric ornament, the mosaic panel of the arch, the decoration of the walls with blue-and-blue tiles, do not even arouse thoughts about the gravity of the brickwork. Madrasah in the East is an educational institution that served in the Middle Ages as a secondary school and as an institution of higher education - a university - the Ulugbek Madrasa was one of the best spiritual universities of the Xvth century Muslim East.

As the legends say, the famous poet, scientist and philosopher Abdurahman Jami studied in madrasah. Here they also lectured their lectures on mathematics, geometry, logic, natural sciences, sets of teachings about man and the world soul and theology, a whole pleiad of famous scientists - Salah ad-din Musa Qazi-zade Rumi, Giyas ad-din Jemshid al-Kashi, Mawlana Ali Kushchi (full name Ala-ad-din Ali ibn Muhammadmashur).

In the madrasa, Ulugbek himself taught, and as the rector, the ruler and scholar chose a simple but very educated person - Maulian Mohammed Havfi. On the opening day, Havfi Madrasah gave a lecture in the presence of 90 scientists, but no one could understand the lecture, except for Ulugbek himself and Kaza-zade Rumi, his teacher.

The Ulugbek madrasah suffered greatly from time, earthquakes and, especially, during the years of civil strife in the early 18th century. The outer domes, two minarets and most of the residential premises were destroyed. In 1918, book dealers, whose shops were located at the side facade of the building, were the first to notice that the northeastern minaret (on the frontal photos it was right) was set in motion.

Every day, he lurched more and more noticeably, breaking away from the main body of the building. It was clear that the minaret left to itself would soon reach a critical inclination and collapse. Concerned that the minaret could collapse directly into their shops, they decided to let V.L. Vyatkina - a representative of the Samarkand Commission of the Turkomstaris (Committee for museums and the protection of monuments of antiquity, art and nature of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic), the supervisor of the monuments of antiquity of Samarkand.

To rescue the minaret, as well as the restoration of ancient monuments of Samarkand, in May 1920, a special commission for the protection of monuments of antiquity and art - Samkomstaris - was organized at Turkomstaris, which included three sections: technical, construction, art and archaeological.

As a temporary measure, the minaret was girded with a wooden corset, and 24 inclined steel cables weighing 36 tons, which were reinforced on wooden anchors dug into the ground just northeast of the modern wooden podium for performances, intercepted a leaning trunk.

As a result, the minaret stopped its lurch at around 1.8 m from the normal position. About how important it was to preserve the monument, M.E. Masson writes the following: "The commission members were clearly aware that the famous Ulugbek Madrasa is a monument of great scientific and artistic significance, and that its main facade without a single angular minaret will be unacceptably disfigured," as one of the four minarets of the madrasah collapsed in 1870, a little later - and the second.

Proposed two ways of straightening. Engineer B.N.Kastalsky proposed to disassemble the minaret brick by brick and re-restore it in the same form. Regional architect M.F. Mauer argued that such a “restoration” would actually destroy the ancient monument.

In its place will have no scientific value and, perhaps, even an ugly construction. The second method proposed by M.F. Mauer was to "tear" the minaret from the building, swing it, straighten it and put it in its place. Hot debates between the two engineers and their supporters went on for a very long time - throughout the entire period that other work was being done.

On June 5, 1920, M.F. Mauer, where he insisted on urgent work. The Commission made the following decision: “to start the construction and technical section for the immediate work on straightening and maintaining the minaret ... and putting it out of any queue.”

Since the disputes between B.N. Kastalsky, his supporters and M.F. Mauer continued and arose at each meeting of the Commission; authoritative technical consultants from Tashkent and from the center were invited, who were more and more inclined to favor the proposal of M.F. Mauer.

The latter carried out a large amount of research work, having studied and collected all the materials on the madrasa and in order to be able to pick up the additional meaning of historical texts himself, he began to study the Persian language.

“At the Registan, Mikhail Fedorovich personally carried out detailed architectural measurements of the madrasah under study and conducted careful observations of the condition tied up on steel cables of the minaret,” writes M.Ye. Masson, recalling those years.

Based on the proposal of M.F. Mauer in Moscow twice drafted a project to straighten the monument. The first was rejected because of the inconsistency with the characteristics of the structure, the second was developed by the outstanding Russian engineer Vladimir Grigorievich Shukhov, to whom Mauer traveled to discuss the details of the project.

The author of the radio tower on Shabolovka, the openwork domes of GUM, Metropol, Petrovsky Passage and other unique structures, as always, approached the solution of the problem in an extraordinary way. His idea was amazingly simple.

In general, it looked like this: under the base of the minaret - a huge structure weighing about 2.5 thousand tons, 35 m high - you need to bring strong rolling beams, and lift the long end of the beams on the side of the slope of the minaret like a lever.

Free voids at the base of the minaret, left after its straightening, pour concrete. That's all. According to the testimony of Professor A.V. Kuznetsova, at first this thought seemed unexpected and impossible to everyone. But Shukhov proved that it is much easier to lower the minaret than to lift it, if only because the lowering is done under the action of its own weight of the structure, and not by the efforts created by the lifting mechanism.

The second important advantage of this method is that the less the whole mass of the minaret moves, the easier it will be to protect it from possible jolts during the restoration work. The idea was accepted for implementation. In 1927, the project M.F. Mauer Moscow plant "Mosmet" under the direction of VG Shukhov made a metal structure and sent it to Samarkand.

She was to be placed and fortified at the base of the minaret. When viewed from her, M.F. To his dismay, Mauer discovered some inaccuracies that "in the practical implementation of the project could lead to disastrous consequences." As a result, he had to go back to Moscow with the sent design and prove that there were any miscalculations.

By 1931, the minaret's roll had increased to 5 ° 1 ', which already threatened him with a collapse. The projection of the center of gravity of the minaret on a horizontal surface shifted from the axis of the basement by 1055 mm. There was no time to delay. Straightening project Shukhov began.

A few days before the cutting of the groove for the first of the fifteen beams, the lower part of the laying of the minaret, somewhat above the intended level of cutting, was covered by a ferrule and alabaster cage. The possibility of using this material has been previously tested by experience.

The beams leaned on the box, the square in the plan design - "rocker", covering the body of the minaret. They were brought alternately under the laying, cut to the appropriate width, and with the help of wedges installed on the "rocker" so that the gap between the upper girder beam and the bottom plane of iron and alabaster cage was 2-4 cm.

Then a wedge was made, which reduced the thickness of the alabaster layer by about 1 cm. Two riveted solid walls of the beam used to transfer pressure to the balancers, and the other two, perpendicular to them, bound them, preventing them from tipping.

Each of the two balancers, 1275 mm long, 89.2 mm thick at one edge, 147 mm thick at the other, rested on a powerful riveted beam located under it (purlin). The path, which passed the swinging point of the balancer, was 1174.8 mm.

Between the balance bar and the girder, four balance plates 75 mm thick were laid horizontally horizontally, along which the balance bar rolled. A thick lead band was laid on the plates under the rocker, necessary for a more even pressure distribution.

For greater safety and to prevent the minaret from tipping over in the event of a possible cable breakage or waist-up, temporary supports mounted on the wedges were held on both sides of the balancing device. These props were steel cushions with an upper cylindrical surface.

As the "yoke" turned, the pillows moved to new places. Extreme cushions on each side rested on wedges of elm, which is about the hardness of oak. All elements of the main supporting structures were arranged in such a way as to ensure free access to the place where the old was cut down, and it was necessary to bring a new laying.

The minaret was rotated using a system of cables covering its hull 9 - 10 meters above the yoke. To avoid damage to the exterior cladding patterns, soft wood planks were placed under the cables.

March 11, 1932 V.G. Shukhov received a letter from Samarkand from the architect Mauer. It said:

"Dear Vladimir Grigorievich!

The straightening of the minaret is complete, and now it relies on columns and a system of beams of the structure that you have designed. Simultaneously with this letter I send several photographs illustrating the course of the works produced, here I will try to be of few words. Due to the prevailing circumstances and local conditions, the work was done slowly and with long interruptions. When assembling the columns, it was found that the markings of the riveted holes in the seams interfacing the girders with the columns were made very inaccurately, diverging in many cases to the floor of the diameter of the riveted rods. In addition to the use of conventional, rather unsatisfactory, ways to eliminate this drawback, I ordered the columns to be embedded in concrete down to the lower belts of the girders, in order to reduce the pressure attributable to these rivets. Crossing the minaret array and laying the platform beams did not cause any complications. Despite the presence of many cracks in the base of the upper massif, the adhesion of alabaster in the joints of masonry with brick turned out to be very strong, not a single brick fragment fell off during the work and, as far as could be traced, not a single new crack appeared . Wedges were put forward without how many - any significant effort, and the turnaround of the minaret was completed on indices on the balancers and plates by rotating the screw. It was observed that unscrewing and re-screwing it (trial) with a wrench with a 60-70 cm handle could be done by one person and very easily. This circumstance allows us to conclude that the error in determining the center of gravity of the minaret was small. Straightening was started on January 7 after the lunch break with a rather strong wind that could not be reckoned with, and ended on January 11 in the afternoon; in this interval was one day off. In the near future, I intend to proceed with the eyeliner for a straightened array of the bottom of the newly restored minaret. When I finish this, which will probably not happen until May, I will not fail to send you photos.

Dear M. Mauer ".

So successfully completed many years of painstaking work. But before this happy and at the same time disturbing event, the wooden anchors dug into the ground changed several times. M.E. Masson, recalling the restoration process, writes: “the huge trunk of the minaret was completely separated from its base and fixed on a frame with rods.

All its damaged lower part from the basement to a height of several meters was removed. It was replaced with capital reinforced concrete masonry ... Within a few hours the minaret's trunk was slowly swung in the opposite direction of the fall and straightened. "

The only publication devoted to this grand project is the brochure of academician M.Ye. Masson's "Falling Minaret" (Tashkent, 1968), who was a direct participant in the events of those years.

Enlightener:

http://samcity.uz