Вы здесь

First mention of Astana.

Study tours on history of Astana.

“In order not to stray from the track, we scouted where the Sultan of Khudai-Menda, famous for unlimited respect and authority over neighboring Kyrgyzs, wanders with the Kopyt (Karpykovskaya - A. D.) volost, hoping to beg him counselors who know safe and secure places. We were notified that he was wandering behind the Ishim River, near the Nura River, at the Akmule tract. The next day we went to Ishim, crossed the river at the Khotai-Bergen tract and stopped at this place for three days. Cossacks caught white fish, and the whole caravan ate it. Having made advice with the caravan, we sent to the Sultan of Khudai-Mende, so that he would provide us with 2 counselors and let us go with the caravan along his volost... The Sultan of Hudai-Menda gave us guides for his 16-year-old son, Sultan Kongur-Ulju Balkhair’s nephew"

"Notes on some peoples and lands of the middle part of Asia, Philip Nazarov, a separate Siberian translator corps, sent to Kokand in 1813 and 1814."

Historic sights of Astana.

Central Kazakhstan (Saryarka) is mentioned in the works of ancient Greek, Chinese, Arab, Persian and Central Asian historians, in the notes of the 13th century Flemish traveler Willem Rubruk. The news about him was also postponed in Russian documents - annals, “interrogative speeches”, diaries of merchants and ambassadors, “skips” of captives and servicemen escaping from captivity, accompanying trade and embassy caravans through the “wild field”. In the XVI century, from the Turkic-speaking kindred tribes, similar in language, type of economy, and material cultural life, independent nomadic Kazakh khanates were formed - the Younger, Middle, and Senior Zhuzes, or, as they were also called, the Younger, Middle, and Senior Hordes.

The younger zhuz occupied the territory between the rivers Syr Darya, Emba, Irgiz, Ural, Or, Ilek, the Middle - between Sarysu, Turgay, Ishim, Nura, Irtysh, the Elder - in Semirechye and Balkhash. Russia has long been interested in trade and diplomatic relations with the formed Kazakh khanates, which, in turn, sought support from her in the fight against external and internal enemies.

With the advent of Russian cities in Western Siberia, especially Tobolsk (founded in 1587 by the Cossack detachment of Danila Chulkov), which turned into the administrative and political center and the residence of the Siberian governor, the relationship between Russia, Kazakhstan and Central Asia expanded, which required more thorough knowledge and adjacent lands, and the peoples inhabiting them, and the means of communication.

Towards the end of the 16th century, the Book of the Great Drawing appeared in Russia. It also indicates the rivers through which caravans from Tobolsk went to Central Asia. Peter I, reorganizing industry, the army, navy, and commerce, was looking for the most convenient trade routes, places of occurrence of natural wealth.

His gaze was not accidentally turned to the East. The tsar instructed the Tobolsk cartographer S.U. Remezov to draw up a history and a map of Siberia (which then included part of Kazakhstan). Remezov, of course, could not physically overpower alone the enormous volume of such work.

I had to use old maps from the archives, and somewhere myself to ask experienced people and based on their testimonies make notes in the drawings. Great help was given to him by Fedor Skibin and Matvey Troshin, who in 1694 traveled from Tobolsk as ambassadors to the Kazakh Khan Tauke.

The result of painstaking work was the Drawing Book of Siberia, completed in January 1701, the first geographical atlas of Siberia and Kazakhstan on 20 sheets. Kazakhstan entered the "Drawing of the land of the anhydrous and low-pass stone steppe."

In addition to mountains and rivers, the author indicated archaeological sites on the drawing. The "Atlas of Asian Russia", published in 1914 in St. Petersburg by the Migration Board, is stored in the Tselinograd Museum of History and Local Lore.

The atlas reproduces one of Remezov's maps - "A drawing of all Siberian cities and lands." Together with the names “Tobolesk city”, “Irtysh”, “Tobol”, “Ishim”, you can read “Cossack horde”, “Lake Kurgalchin”, and in the Ishim valley you can see notes: “mosques”, “prayer house”. At the same time, Remezov created "Siberian History" ("Remezovskaya Chronicle").

In it, he dealt with various events. Describing the end of the Siberian Khan Kuchum, he reported, in particular, that, having been defeated by the Russians, Kuchum captured a lot of cattle from Kalmyks, after which he ran to the feet of the Prishim steppe with the remnants, but was overtaken by Kalmyks "on Nor Ishim near Lake Kurgalchin" and then completely defeated.

As you know, in the process of its historical formation and development, the Kazakh people experienced many disasters caused by the conquerors, encroaching on their freedom and independence. He especially suffered from raids by the Dzungars.

At critical moments, the Kazakh khans repeatedly appealed to the Russian state for help, raised the issue of Russian citizenship. For example, negotiations were held about this in 1594 with Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich Khan Tevekkel, in 1717 with Peter I - Khan Tauke, in 1726 - Khan Abulkhair.

But the circumstances of those years for various reasons did not lead desired results. With the same request in 1730, Khan Abulkhair turned to Tsarina Anna Ioannovna. On February 19, 1731, a letter was signed on the voluntary entry of the Younger Zhuz into Russian citizenship.

This event was a turning point in the fate of the entire Kazakh people. The Russian state in economic, military and cultural relations stood much higher than its eastern neighbors, was really able to protect Kazakhstan from the encroachments of the invaders.

On the one hand, because of the colonialist policy of tsarism, the situation of the Kazakh working masses worsened, because the oppression of the Russian autocracy, officials, kulaks, merchants, industrialists was added to the local feudal-Bai oppression.

On the other hand, the Kazakh people escaped even more difficult enslavement and physical extermination, which were constantly threatened by the Central Asian khanates. The rapprochement of two friendly peoples - Russian and Kazakh, has long nurtured mutual sympathy.

Having joined the great Russian culture, the Kazakh people took the only true path of their further development. The correctness of this path was confirmed by the whole subsequent course of history. The rapprochement of the Russian and Kazakh peoples was not an accident. It had a centuries-old, naturally established basis.

Thanks to the voluntary accession of Kazakhstan to Russia, its study has become more systematic and versatile. We meet scientific information about Priishimye with VN Tatishchev, an outstanding statesman and public figure of the Petrine era, one of the founders of Russian historical and geographical science.

For example, in his “General Geographical Description of All Siberia” dating back to 1736, he wrote that the Ishim River originates in the mountains, is repeatedly lost in swamps, that the water in it at first is “acidic and astringent from the many alum earth through which it passes ”, and then“ with the help of other rivers it is quite corrected and does not become impoverished with the satisfaction of fish ”.

In 1762, the book "Topography of the Orenburg, that is, a detailed description of the Orenburg province, composed by a college adviser and the imperial Academy of Sciences correspondent Peter Rychkov" was published in St. Petersburg.

Introducing readers to the Kazakh steppe, P. I. Rychkov mentioned the disappeared city of Tatagai, located near the current village of Kurgaldzhino: “Tatagai are the ruins of a great city in the Kyrgyz Kaisak Middle Horde on the Nura River, which flowed into the Kurgalzhin lake from the mouth of this river verst from thirty.

According to signs, this city was about ten versts away, and you can still see the quadrangular chambers like a castle so large that they are planted around three hundred around. There is one mosque and a lot of decaying stone structure. Kyrgyz say that in the old days Nogais lived here.”

The son of Peter Ivanovich - N.P. Rychkov - together with academician P.S. Pallas, as part of the detachment of Major General Traubenberg, drove from Orsk to Ulutau. He outlined his observations in the “Daytime Notes of the Captain Nikolai Rychkov’s Travel to the Kyrgyz-Kaisak Steppe in 1771”, a year later published by the Russian Academy of Sciences. N. P. Rychkov discovered in the area of modern Dzhezkazgan "a great many copper ores dug by the ancient inhabitants."

Mining engineer I.P. Shangin did a lot, in 1815-1816 he examined the steppe in the region of Petropavlovsk and the then-non-existent Kokchetav, Atbasar and Akmolinsk. Shangin was looking for deposits of natural resources, traces of past mining, but along the way he also described the archaeological sites he encountered.

The consequence of this scientific expedition was the work “Daytime Travel Notes in the Steppes of the Kyrgyz Kaisaks of the Middle Horde of the Kolyvano-Voskresensky Bergsvorner Ivan Shangin Plants”, extracts from which were published in 1816 in several issues of Vestnik Evropy, and in 1820 in the Siberian Herald , and in 1883 - in the "Mountain Journal".

Thanks to Shangin, science has learned about many monuments of ancient material culture. He spoke about the remains of fortresses and settlements on Ishim and the Akkairak river flowing into Ishim, the Ulutau cave of Aydagarly.

Mausoleums and burials located in the valleys of the Zhaksy-Kon, Zhaman-Kon and Nura rivers; a large shaft constructed of correctly hewn quadrangular porphyry stones, which he met when he examined the Atbasar steppe. I.P. Shangin personally checked the messages of P.I. Rychkov about Tatagay, confirming that such a city really existed.

Among the ruins, he singled out a brick building, which, in his opinion, served as a temple, had inside the columns and plastered walls. On the right bank of the Nura River, 50 versts from Lake Kurgaldzhin, Shangin described the ruins of the fortification.

Traces of Tatagay (locals call him Bytogay) survived to this day in the form of grassy, soddy mounds. Excavations were not carried out. When examining the settlement, the expedition of the Tselinograd Regional Museum of History and Local Lore made two small pits.

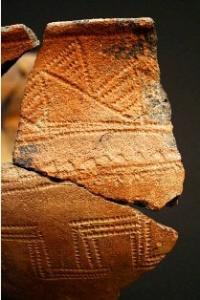

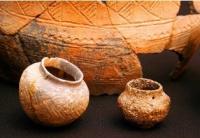

They extracted several square white bricks that are exhibited in the museum in Philip Nazarov, Separate Siberian Corps of the Translator, sent to Kokand in 1813 and 1814 ”, published in 1821 by the Academy of Sciences.

In 1813, the commander of the troops of the Siberian lines G.I.Glazenap sent Nazarov to the Kokand ruler Omarkhan to settle the conflict in connection with the accidental murder in Petropavlovsk of the Kokand envoy returning from St. Petersburg from the royal reception.

Following through the Priishimsky steppe, Nazarov kept records. In his travel observations, a penetrating mind was reflected, capable of objective judgments about the surrounding reality. Nazarov’s attention was attracted not only by the practical goals of the trip, but also by the peculiar nature of Saryarka.

“These wild places and the silence reigning in the vicinity produce some inexplicable despondency,” - sadly, as if he fixes it in passing - we quite clearly imagine the desert along which Nazarov’s exhausting, many-day journey took place.

The notes were made carefully and in detail: “In order not to get off the track, we scouted Sultan Khudai-Menda, famous for unlimited respect and authority over neighboring Kirghiz, wandering from the Kopyt (Karpykovskaya - A. D.) volost, hoping to beg the counselors who know water and safe places.

We were notified that he was wandering behind the Ishim River, near the Nura River, at the Akmule tract. The next day we went to Ishim, crossed the river at the Khotai-Bergen tract and stopped at this place for three days. Cossacks caught white fish, and the whole caravan ate it.

Having made advice with the caravan, we sent to the Sultan of Khudai-Mende, so that he would provide us with 2 counselors and let us go with the caravan along his volost... The Sultan of Hudai-Menda gave us guides for his 16-year-old son, Sultan Kongur-Ulju Balkhair’s nephew.”

Of interest are local history "Notes on the Kirghiz Kaisaks of the Middle Horde," which Colonel S. B. Bronevsky in 1825 led during his passage through the Atbasar and Akmola steppes, and in 1830 published them in the "Domestic Notes".

In 1830 - 1831, on behalf of the founder of Akmolinsk F.I. Shubin, the centurion Shakhmatov, having twice visited summer expeditions in the vicinity, plotted the southwestern part of the modern Tselinograd region on a topographic map, described Lake Kurgaldzhin, and painted the ruins of Tatagay.

The most fundamental researchers of the first half of the last century include A. I. Levshin. A. Pushkin praised his article “Ethnographic News of the Kirghiz-Kaisatsky, or Kyrgyz-Cossack Hordes” and in 1831 secured its publication in the Literary Newspaper.

The three-volume “Description of the Kyrgyz Cossack, or Kyrgyz Kaisatsky, Hordes and Steppes” by A. I. Levshin was published in St. Petersburg in 1832. It is accompanied by a geographical map of Kazakhstan at the level of knowledge of that time, contains a variety of material about the nomads located along Tobol, Ishim, Nur, Sarys, Kulan-Utpes, Zhaksa-Kon, Zhaman-Kon and the lakes of the Kurgaldzhin system.

Levshin was the first Russian scholar to speak out against the incorrect name of the Kazakhs. “Coming to the historical description of the Kyrgyz-Kaisakov,” he said, “the first duty is to honor the fact that they are given a foreign name in Europe, which neither they themselves nor their neighbors, excluding Russians, call them...

Let's say that the name The Cossack, who transferred to many branches of the Russian tribe in the Middle Ages, belongs to the Kirghiz-Kaisatsky hordes from the beginning of their existence, and that they still do not call themselves otherwise like Cossacks (Cossacks).

Under the same name they are known to the Persians, Bukhara, Khiva and other peoples of Asia. Until the XVIIIth century, even in Russia they did not know the Kyrgyz Kaisaks, but called them Cossacks, the Cossack horde.”

The protests of the scientist, of course, did not change anything - conservative dignitaries reacted to them indifferently. Nevertheless, the statements of Levshin left a mark in the consciousness of the progressive Russian and Kazakh public.

Ch. C. Valikhanov, who respected Levshin with great respect, called him Herodotus of the Kazakh people. The works of A. I. Levshin and now have not lost their scientific value, are widely used by researchers. Northern and Central Kazakhstan with its natural wealth, ancient history and culture attracted unflagging attention.

From year to year, the number of essays, articles, diary entries and books covering various issues of the distant past and present has increased in the domestic and foreign press. In our country, this was mainly done by officers and government officials who combined official duties with research.

Authority:

Dubitsky A. F. “City on Ishim” Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1986, 152 pp.