Вы здесь

Semenov Tyan-Shansky in Lepsinsk.

Semenov Tyan-Shansky's journey through Kazakhstan.

"The rest of the area is occupied by nomads - Kirghiz of the volosts of the Lepsinsky district. The productivity of the area and its means of subsistence are so sufficient that in terms of food, a force of 15-29 companies with a corresponding number of cavalry and artillery cannot encounter any difficulties. Bread supplies (wheat and oats) are in great abundance in each settlement. From the nomads it is always possible to obtain portioned cattle, yurts, horses and camels for transport. If necessary, armed settled residents will provide serious support to the troops. Excellent guides, horsemen and scouts can always be found among the nomadic population, whose conscientious service has been repeatedly confirmed by facts in the Central Asian wars."

V. P. Tikhmenev, I. T. Poslavsky. "Military Review of Eastern Border Strip of Semirechye Region." 1883.

Pickets from Semipalatinsk to Verny.

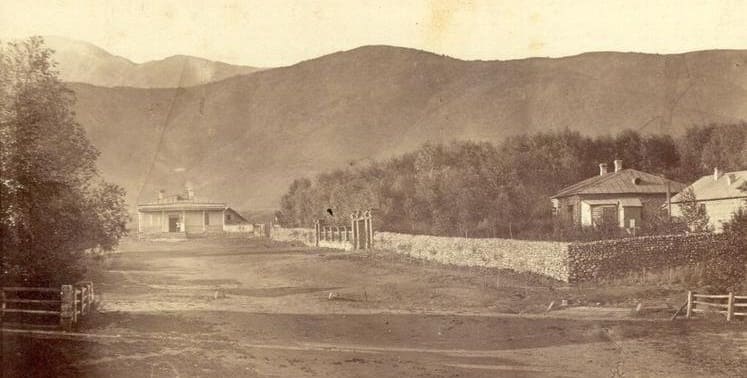

After several easy passes, about twenty miles from our overnight stop on Terekty, we began to descend into the valley of the Lepsy River and finally saw the Chubaragach, or Lepsinskoye, settlement, located at the confluence of two branches that form this river in the longitudinal valley of the Semirechye Alatau, which has the shape of an elongated ellipse about twelve miles long and up to 7 wide, surrounded by mountains on all sides; the main axis of this ellipse was directed from the S-W.

Both merging branches originated in a high chain, which bounded the elliptical valley from the southeast, and after their confluence the united river (Lepsa) broke through the wild gorges of a less high chain, which bounded the elliptical valley from the southwest.

In 1857 there was no road through this gorge; it passed through a not particularly high and treeless pass of the northwestern chain. The southeastern chain, higher than the northwestern, had snowy meadows on its peaks, and its slope, facing the elliptical valley, at the bottom of which the Lepsinsky settlement was located, was completely covered with a variety of deciduous forest, and bore the name of Chubaragach (variegated forest) and fully justified it, especially in its wonderful autumn attire. In general, the Chubaragach Valley is a place, although not as grandiose as the valleys of the Tien-Shan and the Zailiysky Alatau, but no less attractive than the best valleys of the French Vosges and the Hardt in the Bavarian Palatinate, with which they have a great resemblance in their autumn attire.

The hypsometric determination gave me 820 meters of absolute height for the bottom of the Chubaragach Valley. The Lepsinsky settlement was quite well built from aspen forest, and only the window sills and jambs were made of spruce forest. In 1857, there were 440 houses in the Lepsinsky settlement, and the inhabitants were: male and female Cossacks - 763 people, male and female peasants 1453 people.

The settlers of this Russian colony in Central Asia, both peasants and Cossacks, were extremely pleased with the climatic conditions of the country and, in particular, its spaciousness and fertility, although, due to unaccustomedness to local climatic conditions, illnesses were frequent at first.

But these illnesses depended mainly on conditions inevitably connected with the colonization process itself. The prevailing illnesses - scurvy, dysentery in children and fever - were especially caused by the failure to adapt to local conditions, the lack of shelter in a climate that was quite rainy and subject to rapid temperature changes, the insufficient medical care, poor care of children during the first intensive field and construction work and the abuse of fruits and berries. In 1857, the Lepsinsky settlement had 105 dessiatines of winter grain (rye) and 753 dessiatines of spring grain (245 dessiatines of wheat, 210 dessiatines of spring wheat, 194 dessiatines of oats, 60 dessiatines of barley, 25 dessiatines of millet, and 19 dessiatines of peas).

In addition, there were 30 dessiatines of flax and 1 dessiatine of hemp. The yield of these grains over the last three years was as follows: 40 dessiatines of millet, 15 to 20 dessiatines of wheat, 12 to 15 dessiatines of rye and spring wheat, and 6 to 10 dessiatines of oats.

The yields of flax and hemp were also excellent. The bread in the Chubaragach Valley, with a fairly rainy climate, especially in the first half of the summer, does not need watering, but with watering (by no means more than once during the entire summer) it yields more grain.

The feed for the cattle is incredibly good, since the grasses grow here no less luxuriously than in the best Altai valleys. Only some vegetables, namely cucumbers, watermelons and melons, do not ripen due to early frost, which is the only defect of the wonderful climate of the Chubaragach Valley.

During my entire visit to this valley (in mid-September 1857), the temperature in the mornings was low and frost began already at the beginning of September. On September 18, early in the morning, I undertook a horseback ride into the mountains, accompanied by two well-acquainted the surrounding area of the Cossacks, heading for the very mountain pass along which Karelin ascended the Semirechensky Alatau in 1840.

Our ascent began already one verst to the southeast of the village. The entire mountain slope was covered with a beautiful deciduous forest (chubar-agach), which included the following trees and shrubs: aspen (Populus tremula), poplar (Populus nigra, P. laurifolia), birch (Betula alba), several species of willow (Salix pentandra, S. fragilis, S. alba, S. amygdalina, S. purpurea, S. viminalis, S. stipularis, S. capraea, S. sibirica), wild apple (Pyrus malus, P. Sieversii), rowan (Pyrus aucuparia), bird cherry (Prunus padus), and from the shrubs two species of boyarka - red and black (Crataegus sanguinea, C. melanocarpa), argay (Cotoneaster nummularia, Potentilla fruticosa), raspberry (Rubus idaeus), wild gooseberry and currant (Ribes aciculare, Rib. heterotrichum, R. rubrum), buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), Siberian acacia (Caragana frutescens), honeysuckle species (Lonicera tatarica, L. xylosteum, L. hispida, L. coerulea, L. microphylla), viburnum (Viburnum opulus), cherganak (Berberis heteropoda).

The densely growing trees were in places heavily intertwined with local vines: clematis species (Clematis orientalis, Atragene alpina) and hops (Humulus lupulus). There was no coniferous forest in Chubar-aga-e yet. As we climbed south, we crossed a spring that the Cossacks called Beremesev, and five miles from the village we came to a more significant tributary of the B. Lepsy, along which logging was taking place.

The rock outcrops I encountered along the way consisted of greywacke slate with unclear stratification and barely reaching the surface of the soil. Coniferous trees (Picea Schrenkiana) also came across a tributary of the B. Lepsy. In the upper reaches of this tributary we began to climb steeply uphill, first to the southeast, then gradually turned, first to the east and finally to the northeast.

The motley forest (chubar-agach) was gradually replaced by grasses, although faded, but surpassing the height of a rider on a horse. These herbs belonged to the families of Malvaceae (Althea ficifolia), Umbelliferae (Sium lancifolium, Bupleurum aureum, Bupl. exaltatum, Conioselinum Fischeri, Ferula soongorica, Anthriscus sylvestris, An. nemorosa, Conium masulatum, Schrenkia vaginata), Compositae (Inula halenium, Lappa tornentosa, Cirsium heterophyllum, Cirsium arvense, Onopordon acanthium), cereals (Dactylis glomerata, Elymus sibiricus, Deschampsia caespitosa, Calamadrostis sylvatica, Milium effisum, Lasiagrostis splendens). In places these herbs were heavily entwined with mouse peas, which reached their tops.

Sometimes luxurious thickets of grass alternated with groves of trees, of which the groves of apple trees had the appearance of garden plantings; the apples at this time of year were already completely ripe and seemed very tasty to us. As we continued to climb, the slate suddenly gave way to granite, first fine-grained, with a stock coming to the surface, and then coarse-grained.

Firs still clung to its flat rocks, but then the forest vegetation completely disappeared. Potentilla fruticosa and juniper (Juniperus sabina), creeping along the flat rocks, grew among the bushes. But these flat rocks soon changed to sharply protruding ones in the form of teeth or vertically placed books.

Our road, having climbed the ridge separating the tributary of the Lepsy from its main stream, went further along easy passes, winding between the rocks almost at the same level, only slightly rising, and the vegetation here was already completely alpine, although already very faded, but still I could distinguish some plants, such as: Papaver alpinum, Alsine verna, Cerastium maximum, Ledum gelidum, Arnebia perennis, Aster alpinus, Ast. flaccidus, four species of gentian (Gentiana aurea, G. frigida, G. macrophylla, G. verna) and Dracocophalum altaiense.

As we went forward, we encountered between the rocks more and more piles of fresh snow, packed by the blizzard. The wind was unbearable in its strength and cold. We were forced to turn west and even northwest to get to the descent into the main Lepsy, and thus from the granites we came out again onto the slates, the strike of which this time was completely clear, and the fall was vertical (85° to the N-W).

From here a wonderful view of the highest part of the Semirechensky Alatau opened up before us. It is here that the upper valley of the Lepsy, bending for ten miles, changes its direction: it was directed from the West of the North-West to the East of the South-East perpendicular to the axis of the ridge, but here it turned almost at a right angle and flowed from the South of the South-West to the North of the North-East, that is, almost from the South to the North, longitudinally relative to the strike of the slates.

At the head of the valley was the most significant of the whites, and from it a wide snow mantle descended to two or three sources of the Lepsy. The upper longitudinal valley of the Lepsy was a little more than a verst wide, its slopes were soft, and the bottom was covered with spruce, although quite sparsely, since forest vegetation here already reaches its limit.

Along the valley, a river meanders, My intention to get through the Lepsinsky pass to the Chinese side was not crowned with success. Having seen with my own eyes that the mountain pass was covered with snow at that time, and the weather ahead was unfavorable, I decided to go back.

There was no point in descending to the upper valley of Lepsy, we returned along the same road along which we had ascended. It was getting dark when we reached the granite teeth, and already in the darkness of the night we descended to the first spring, where we spent the night in a beautiful grove consisting of birches, aspens and apple trees.

This pass was the same one that Karelin had passed through in 1840. On September 19, we returned to Chubar-Agach along the same path, in cloudy weather. From the mountains, the entire village looked like a chessboard. It was visible how, flowing behind the village, the rivers made their way through the forward ridge after their confluence in a wild gorge. In my time there was no road in this gorge, and it was impossible to get to Chubar-Agach from the west except through the ridge, although not high.

Snow in Chubar-Agach itself usually falls finally only in December, and on the western slope of the front ridge even later, and lasts only until March. At this time of year a good sled road is established here; in general, the winter is very mild, and there are no significant colds at all.

Having spent the night in the Lepsinskaya stanitsa, I decided to leave it on September 20. Waking up at seven o'clock in the morning, I was unexpectedly struck by a completely winter picture. Everything was covered with thick hoarfrost. There was no grass visible, except for tall cereals (Dactylis, Calamagrostis, Lasiagrostis), but even they drooped their ears under the weight of the hoarfrost, with which even the laurel-leaved poplars were completely whitened.

The thick fog did not allow us to distinguish objects more than twenty steps away. Nevertheless, we set off and, having crossed about two miles across the valley, began to quickly climb its slope in a westward direction. A remarkable sight awaited us on this path.

The fog began to thin quickly and ended abruptly, almost like a wall, beyond which, as we continued to climb, the sky was already clear and transparent. Not a single cloud was visible from the top of the pass, the sun was shining warmly and brightly, the thermometer showed 12° C at 8 o'clock in the morning, the snowy peaks of the Semirechensky Alatau were completely cloudless and sparkled brightly in the sun's rays, which beautifully illuminated the slopes of the forest zone in its motley autumn attire of chubar-agacha.

Not a single drop of dew was visible on the still fresh grass of the mountain pass. But at our feet in the Lepsinskaya valley, the entire wide elliptical basin, twelve miles long and seven wide, was a real "mare vaporum". Its color was milky-grayish-white, similar to the color of cumulus clouds.

At first it seemed to sway slightly, but from the very top of the pass its surface seemed completely horizontal. Not a single spot was visible on this milky sea, and nothing in it betrayed its character. The same hot sun and the same dryness of the atmosphere accompanied us not only on our ascent to the top of the pass, but also on the descent from it into the low valley, during which we were getting closer and closer to Lepsy, which had burst out of the gorge and was curving like a beautiful ribbon along the valley.

On the right bank of the river a wide space was occupied by Chubaragach arable land, and on the left a slightly hilly area, over a space of four to five square miles, presented a huge black spot from the fire that had occurred the previous night.

Authority:

P. P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky. "Journey to Tien Shan". 1856 - 1857.