You are here

Military operations in Lepsinsky district from 1920 to 1928.

Historical facts of Lepsinsk.

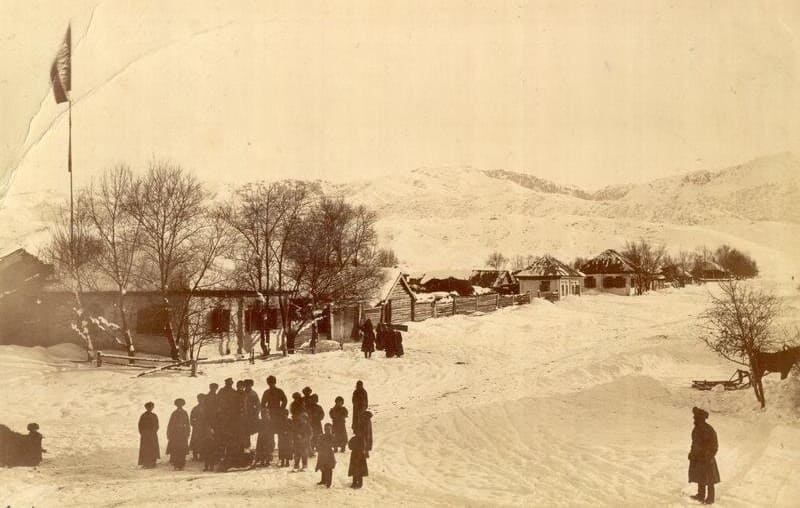

"The village of Verkhlepsinskaya of the 10th Regimental District of the Siberian Cossack Army is one of the best areas in the Semirechensky region of the Semipalatinsk region, both in terms of its position and soil quality, and in terms of healthy air, abundant vegetation in its vicinity of various kinds of trees, fruitful bushes and herbs and finally on the various benefits and conveniences of life."

Semipalatinsk local historian N.A. Abramov.

Trip from Almaty to Lepsi.

In 1847, intensive Cossack colonization of the region began, described in some detail in 1908 by historian N.V. Ledenev in his “History of the Semirechensk Cossack Army”. This is how he outlines the history of the founding of Lepsinsk:

"For settlements on the Lepse River in 1855 - 1856, it was ordered to install two hundred Siberian Cossacks from the 6,7,8 and 9 regiments of the Siberian Linear Cossack Army and 200 peasant families. The first batch of Cossack settlers arrived on June 18, 1855.

Place for settlement was chosen, about 40 versts from the sources of the Lepsy River, the valley of this river greatly expanded here. The Cossacks who settled here founded a settlement, first called the settlement of Lepsinsky, then, after some time, the village of Verkh-Lepsinskaya and then, much later, just Lepsinskaya."

The name Lepsinsk will not tell us anything today - only historians of the White movement should know that this is the last residence of the Orenburg ataman and governor-general of the Semirechensky region A.I. Dutova.

From January 1920 until the Dutovites left for Xinjiang in the spring of that year, Lepsinsk was the capital of the White Semirechye. When the Semirechensky Front was formed, in certain settlements of the northern regions of the region, leadership centers of the white units were also located - in Uch-Aral (headquarters of Ataman B.V. Annenkov), Sergiopol (Semirechensky Military Government), the village of Urdzhar (administration bodies of General Bakich, and after the capture of Kopala - the governing bodies of the Semirechensk Cossack brigade of General Shcherbakov, deputy military chieftain).

In Lepsinsk itself, Dutov was accompanied by a convoy detachment and local Semirek Cossacks. There, probably, there was a sacred relic of the Orenburg Cossack army - the Tabyn Icon of the Mother of God. The names of the first commanders of the Siberian Cossack detachments that settled on the Lepse River are known - military foreman Tychinsky, cornets Laptev and Aleksandrov, commander of the Verkh-Lepsinsky detachment Esaul Ivanov.

Largely due to its isolation from the main postal routes and its dead-end location, the village, locally known as Lepsa, retained its original patriarchal appearance 150 years later: the same solid wooden huts, built in the Siberian traditional style, covered with iron, with carved porches and shutters, and nearby two-story, typically Semirechye Cossack and merchant estates (of which many have been preserved in the historical parts of Kopal, Sarkan, Talgar, Issyk, Kaskelen and Almatakh), shady gardens made of poplars, irrigation ditches along the streets, a cemetery on a hillock and a squat Orthodox church characteristic of Semirechye a temple in the shape of a ship is a typical appearance of Semirechensk Cossack settlements.

In 1906, 75.9% of Russians lived in the city. After the end of active hostilities in 1920, the Russian population dropped to 58.2%, but already in 1923 it rose again to 65.9% due to the return of refugees. During the civil war, northern Semirechye had to become the epicenter of a dramatic confrontation between the Cossacks and the newly settled peasants, recent settlers in the region.

At the heart of the conflict was an unresolved land issue, which escalated into an armed confrontation. Most of the Cossacks joined the White movement, the peasants supported Soviet power. The Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries, having seized power in the regional center - the town of Verny - in early March 1918, brutally suppressed the Cossack uprising that broke out.

Many Trans-Ili villages were literally razed to the ground, and the population itself was either destroyed or fled to the north of the region and to the Chinese border with the military chieftain A.M. Popov. From the summer of 1918 until the spring of 1920, only Lepsinsky and the northern part of Kopalsky districts remained a hotbed of resistance.

After a detachment under the command of Colonel Yarushin arrived from Semipalatinsk in northern Semirechye and occupied Sergiopol, a new wave of Cossack uprisings broke out here. Semireki managed to take control of the villages of Sarkan, Topolevka, Kopal, Aksu, Urdzhar, settlements Kargaly, Baskan and a number of peasant villages.

The Reds were driven out of Lepsinsk by a detachment of Captain Ushakov, and from Urdzhar, Makanchi and Bakhtov by a detachment of Captain Vinogradov. At the end of 1918, the Partisan detachment of Ataman Annenkov came from Semipalatinsk to help the rebels, significantly strengthening the position of the whites in the north of the region.

This circumstance contributed to the return from China of the Cossacks who had gone there after the failure of the uprising in the Trans-Ili villages - Malaya and Bolshaya Almaty, Sofia, Nadezhdinskaya, Tastakskaya, Kaskelenskaya and Iliskaya.

In the north of the region, Cossack power was revived again, led by the Military Government, legitimately elected at the Military Circle in February 1918. However, for more than a year in the center of the Lepsinsky district, 13 peasant villages remained a hotbed of red resistance - in Soviet historiography called the “Cherkassy defense” (after the village of Cherkasskoye - the center of the uprising).

Only in the autumn of 1919 did Annenkov’s troops manage to suppress it - but time had already been lost, the Reds received reinforcements from Tashkent, Semipalatinsk and Omsk fell. Dutov's Orenburg army was defeated and, with huge losses, arrived in northern Semirechye at the end of 1919, occupying the Sergiopol region - along the Tarbagatai ridge to the Chinese border.

The Annenkovites settled south of the chain of Semirechye lakes - Sassyk-kul, Uyaly and Ala-kul, with headquarters in the village of Stefanovskaya (Uch-Aral). The southern direction - part of the Kopalsky district - was covered by the Semirechensk Cossack brigade of the deputy military chieftain, General Shcherbakov.

In the regions bordering China, in the Dzharkent and Przhevalsky districts, partisan units of Colonel Sidorov operated. After the defeat of the Cherkasy peasants, the Semirechensky Front was able to shift to the south, from the line Aksuyskaya village - Sarkanskaya village - to the pickets of Ak-Ichke, Sary-Bulak - village. Gavrilovskoe.

The villages of Abakumovskaya, Arasan and Kopal were liberated, but there was no longer any strength to advance deeper into the region, to Verny. There was no organized resistance in the rear of the Reds - the Trans-Ili villages were destroyed, and individual pockets in the Issyk-Kul region and border areas could not change the situation.

Considering the current situation, the remnants of the Orenburg army, led by General Bakich, crossed the border in the Bakhtov region, to the Chinese city of Chuguchak; A part of Ataman Annenkov’s Partisan Division moved to the border through the Dzungarian Gate and the Selke (Cholak) Pass.

Leaving Lepsinsk at the end of March 1920 due to the danger of encirclement and uniting with the remnants of Shcherbakov’s detachment (defeated at the village of Arasan), the Dutovites along the Sarkan Gorge and through the Kara-Saryk pass reached the territory of China in the area of the Borotola River.

Thus began history of Russian Cossack emigration in Xinjiang.

On February 7, 1921, Alexander Ilyich Dutov was killed in Suidun by agents of the Cheka during a special operation, the purpose of which was either to kidnap him and take him to Dzharkent, or to kill him. The operation was led by Kasymkhan Chanyshev, who came from a wealthy Tatar merchant family and was the head of the Dzharkent district police.

The group consisted of 9 people (all except Chanyshev and Dungan Jamaz were Uyghurs). Chanyshev, using his connections among the whites and posing as an opponent of Soviet power, capable of raising an uprising in the Dzharkent district, in October 1920 achieved a meeting with A. Dutov.

During this meeting, he was able to gain the trust of the ataman, and also noted Dutov’s tired appearance and a certain skepticism towards his messages and excellent awareness of affairs in Semirechye, which indicated the excellent work of Dutov’s intelligence and counterintelligence.

A month later, Chanyshev went to Dutov again, this time achieving complete trust. Preparations for the kidnapping were in full swing when suddenly Chanyshev was no longer trusted, and the road to the ataman became closed to him.

The security officers, in turn, began to suspect Chanyshev as a double agent, arrested him and took all his immediate relatives hostage. He was given an ultimatum: either he kills Dutov (there was no talk of kidnapping), or all his relatives will be shot.

On the night of January 31 to February 1, 1921, a sabotage group crossed the border. On February 2, they were already in Suidong. Chanyshev wrote a note to Dutov that everything was ready for the uprising, and the action needed to begin immediately: “Mr. Ataman. We've stopped waiting, it's time to start, everything is done. Ready. We’re just waiting for the first shot, then we won’t sleep,” and sends her with his courier Makhmud Khadzhamirov.

They knew him at headquarters; he had previously visited the ataman with instructions from Chanyshev. Therefore, they let him go straight to Dutov’s office, where, in addition to Dutov himself, there was his adjutant, centurion Lopatin.

Khadzhamirov handed the note to the ataman and as soon as he began to read it, he shot him point-blank, then at Lopatin and finished off Dutov, who was lying on the floor. The militants outside the headquarters killed the outer guards, and the entire sabotage group fled Suidong without losses.

On February 11, a telegram was sent from Tashkent about the execution of the task to the chairman of the Turkestan Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars, member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Turkestan Front G. Ya. Sokolnikov, and a copy of the telegram was sent to the Central Committee of the RCP (b).

Members of the group were awarded by F.E. Dzerzhinsky, and in the 1930s all became victims of political repression. The last participant in the operation lived in the Orenburg region (where he was exiled) until his death in 1968

A. Dutov and the two Cossacks killed with him were buried with military honors on the outskirts of Suidun, in a Catholic cemetery. A few days after the funeral, the chieftain’s grave was desecrated: unknown persons dug up his body and beheaded him.

In December 1918, Colonel Boris Annenkov received command of the 2nd Steppe Corps with the order to liberate all of Semirechye from the Reds. In January and April 1919, he fought in the area of the village of Andreevka with varying success.

In July 1919, he fought in the Andreevka area. Annenkov refused to carry out the command’s order to transfer his division to the Western Front under the pretext that the Kyrgyz and Chinese who served in his division did not want to leave the Russian-Chinese border, the Semirechensk Cossacks did not want to leave their homes to be destroyed, etc.

Based on this, that the Annenkov division does not follow the orders of the high command and is an unreliable unit led by an undisciplined commander, Major General Buturlin issued a special order in this regard, which read:

“Colonel Annenkov’s units should not be given weapons until further notice from headquarters, bearing in mind that they will be supplied and armed after their transfer to the Western Theater of Operations.”

Annenkov allocated several regiments to the Eastern Front, but categorically refused to transfer all his forces to the decisive Western Front, since this could undermine the foundations of his power in the small empire he created.

On this basis, the prominent strategist of the Civil War N.E. Kakurin ranked him among the outlying Cossack atamans who did not recognize anyone’s authority other than their own. In his assessment, the separatism of such leaders greatly weakened the white movement as a whole.

At the same time, the regiments transferred by Annenkov showed themselves from the worst side in terms of military discipline - having arrived in Petropavlovsk, Annenkov’s “black hussars” and “blue lancers” engaged in such robberies in Petropavlovsk that there, by the verdict of a military court, 16 people from their numbers.

In August 1919, he became the commander of the Separate Semirechensk Army. Suppressed uprisings in Semipalatinsk and Lepsinsky district. On October 14, 1919, B. Annenkov completed the suppression of the peasant uprising in Lepsinsky district.

They, with very few firearms, created a real front for self-defense and the protection of their families. Although in some publications the Cherkasy-Lepsinsk uprising of 12 Russian villages is considered pro-Soviet, in reality it was rather anti-Annenko.

The Annenkovites were able to break the resistance of the peasants only after the third offensive, when the forces of those besieged in the village of Cherkassy were completely exhausted from hunger, scurvy, and typhus and they were forced to surrender to the mercy of the winner.

Having captured Cherkasskoe, the Annenkovites killed 2,000 peasants there alone, in Kolpakovka 700, in the village of Podgorny another 200. The village of Antonovka was burned and completely destroyed, and in the village of Kara-Bulak, Uch-Aral volost, all the men were killed.

The Bolshevik “Mountain Eagles” movement, led by Yegor Alekseev, created by the peasants of the Urdzhar region, defending in the Khabar-Su mountains, had a similar anti-Annenko character. In negotiations with Annenkov, Alekseev explained that his detachment did not recognize either the Whites, the Reds, or the Provisional Siberian Government.

Alekseev stated that they stand for the power of the peasantry and fight against the provision of In the winter from 1919 to 1920, he took command of Dutov’s units, which retreated to Semirechye after the defeat in September 1919 near Aktobe from the Red Army.

Dutov was appointed by Ataman Annenkov as Governor-General of the Semirechensk Region. However, the arrival of Dutov’s units did not strengthen, but rather weakened the power of the whites in Semirechye, since 90% of those who came were sick with typhus.

The unbridled treatment of the Dutovites by the Annenkovites, which included numerous robberies and violence against them, did not help this either. One of the Orenburg residents who then ended up in Semirechye wrote in his memoirs:

“having listened to all the stories of local residents, eyewitnesses, and judging by Annenkov’s attitude towards the Orenburg residents, it became clear to us that we were in the most powerless place after the Bolsheviks, and if anything the ataman (Annenkov. - A.G.) gets into his head, then he will do it to us.”

Another witness to these events, the White Guard captain Solovyov, while in Chinese emigration, said: “...at the very first pickets, the Dutovites saw the brotherly greetings of the ataman nailed to the wall:

"Every partisan has the right to shoot everyone who did not serve in my units, without trial or investigation. Annenkov." Maybe I paraphrased the words of the slogan, but the meaning is true."

The experienced Urals residents were also unpleasantly struck by the terrorist regime established by Annenkov in Semirechye, as described by the same captain Solovyov:

“Having come into contact with the residents, the Dutovites learned with a feeling of deep indignation about the repressions of their brother-ataman. They did not want to believe in (people) being dragged away by harrows or thrown off cliffs, and only after examining the wounds of those who survived the beatings were they convinced of the truth. Such pointless cruelties did not happen in the distant Orenburg steppes; they were disgusted by them.”

While selecting the most necessary things, Annenkov at the same time refused to supply the Dutovites with ammunition. As Dutov’s General A.S. Bakich wrote already in China, “all my requests to General Annenkov for the supply of cartridges to my units remained fruitless, although there were large quantities of those, which the Reds subsequently got in Ucharal.”

In another letter of his, addressed to generals N. S. Anisimov, A. N. Vagin and G. M. Semenov, Bakich noted that

“the method of command and order in the partisan units of Ataman Annenkov, where the basic requirements of military service were not observed, the legality was denied and order, incredible outrages and robberies were allowed, both in relation to the civilian population of villages and villages, as well as in relation to the ranks of my detachment, who, due to illness, could not stand up for themselves, caused bitterness against the partisans of General Annenkov on the part of the ranks of my detachment.” According to the testimony of those who arrived, the Annenkovites openly declared to the Dutovites, “that they don’t need us (Dutovites - A.G.), that we would get out of the territory of the Semirechensky district.”

Subsequently, already in China, A.S. Bakich asked the Chinese authorities to place units of the Annenkovites separately from his detachment at a distance of no less than 150 miles. He guaranteed the absence of clashes between Annenkovites and Dutovites only if the specified condition was met.

As the reason for such deadly enmity between them, in a letter to the Urumqi Governor-General Jan, General Bakich indicated the murder by Annenkovites at the Chulak Pass of about forty families of officers of his detachment and refugees, while women and girls from 7 to 18 years old were raped by them and then hacked to death.

In February 1920, B. Annenkov, having committed numerous bloody massacres of unarmed people, but never fighting on the Western Front, which Annenkov refused each time under various pretexts, Annenkov’s “partisan division” turned out to be very weak in combat terms.

When Annenkov eventually had to fight with the regular units of the Red Army advancing on Semirechye, his division was immediately defeated and began a continuous retreat. However, Annenkov refused to accept the ultimatum of the Red Army command put forward on February 29, 1920 and to lay down his arms.

In March and April 1920, with a detachment of 18,000, he retreated to the Chinese border, settling at the Selke Pass. An uprising broke out in the Yarushinsky brigade, dragoon regiment and Serbian units of those who did not want to go to China, from where Annenkov planned to continue the fight against the Bolsheviks, suppressed with exceptional cruelty.

In April 1920, the 1st Orenburg Cossack Regiment of military foreman N. E. Zavershinsky separated from Annenkov’s division, or more precisely, from its remnants and went to Dutov. Various White Guard authors' versions of the causes of the events differ strikingly from each other.

One of the authors favorably disposed towards Annenkov writes vaguely about this: The stay of Annenkov’s detachment in the Alatau Mountains was marked by a number of unnecessary and unjustifiable cruelties that were inflicted by some individuals from among the ataman’s close associates against individual partisans and private refugees who sometimes found themselves in the area squad location...

Annenkov’s own version, set out by himself in the Semipalatinsk trial of 1927, was aimed at downplaying the number of victims of this crime, the fact of which he did not deny, and at placing part of the blame for it on the victims themselves.

But the evidence of the Ural Cossacks, including those who wrote about this in China, beyond the reach of Soviet power and in no way interested in compromising the white movement, speaks of something completely different.

Thus, the White Guard officer A. Novokreshchenkov, while in China, wrote about the tragedy at the Selke Pass:

“Approximately in March, on the 16th-19th, Ataman Annenkov’s detachment, under pressure from the Red Army, approached the Chinese border at the Selke Pass. The ataman called this place “Eagle’s Nest” and camped there with a detachment of about 5 thousand people.

Here were the regiment of Ataman Annenkov, or Atamansky, the Orenburg regiment of General Dutov, the Jaeger regiment and the Manchurian regiment with one battery and a sapper division. The Ataman regiment provided cover for the detachment's retreat.

He carried out a trial on the spot of the partisans going home - they were simply stripped and shot, or they informed the armed Kyrgyz that such and such a party was coming and it must be destroyed. The families of some officers went with the detachment to the border, such as, for example, the family of the honored Orenburg resident Colonel Lugovskikh, which consisted of three daughters, an elderly wife, the wife of Yesaul Martemyanov and, among others, the wife and 12-year-old daughter of Sergeant Petrov the Orenburg resident.

The ataman ordered all families to evacuate to China, and he himself immediately gave the order to the 1st hundred of the Ataman regiment and centurion Vasilyev to hand over all the women to the partisans and Kyrgyz, and to kill the men.

As soon as the families began to arrive, the centurion Vasilyev detained them under various pretexts and sent them to the convoy of his hundred, where there were already lovers of violence: Colonel Sergeev - the head of the garrison of Sergiopol, Shulga, Ganaga and others.

The arriving women were undressed, and they passed from hand to hand in drunken groups, and then they were chopped in the most incredible positions. The sergeant's daughter, who had already been raped and had her hand cut off, managed to get out of this cesspool, and she ran to the detachment and told everything.

This was conveyed to the Orenburg residents and asked them to defend themselves. The regiment immediately armed itself, and its commander Zavershensky went with Martemyanov to the ataman and demanded the extradition of the perpetrators.

The ataman did not agree for a long time, delaying time so that the main culprit Vasiliev had the opportunity to escape abroad and thereby cover his tracks. But Zavershensky, under the threat of a revolver, forced the ataman to hand over the criminals.

Orenburg residents arrested Shulga, Ganaga and three or four other people. Volunteers were called in to chop them up. The felling of these people took place in front of the entire detachment. After this execution, the regiment immediately withdrew and went to China, not wanting to remain in the detachment.

Following the regiment, the Annenkovites fired several shots from their guns, fortunately, they did not hit the target... Later, on the orders of General Dutov, an inquiry was made into the management of the emigrants. Vasilyev was caught, arrested, and he died of starvation in the same Orenburg regiment, already in China.”

On April 28, 1920, B. Annenkov left with the remnants of the detachment for China, where he was based in Xinjiang. Before this, Annenkov insidiously invited all willing soldiers and Cossacks to stay in Russia, transferring weapons to Annenkov’s men.

When they completed this, and this turned out to be the majority, they were sent to the non-existent city of Karagach, where carts were allegedly even prepared for them to transport them home. But instead of returning to their homeland, several thousand unarmed people deceived by the ataman were, on his orders, mercilessly killed in the remote area of Aktum, three miles from Lake Alakol (in the Almaty region of modern Kazakhstan).

They were shot in batches of 100 - 120 people and buried in five huge ditches dug by order of Annenkov, two months earlier, and turned into large graves. As it was said in the indictment in the Semipalatinsk trial of 1927, “those who expressed a desire to return to Soviet Russia were stripped, then dressed in rags, and at the moment when they passed the gorges, they were put under machine-gun fire from the Orenburg regiment.”

After this last final massacre on Russian soil, Annenkov’s entire army of once many thousands was reduced to 700 people, with whom he crossed the Chinese border. He took with him a lot of stolen property, including cars, as well as gold and other valuables.

On August 15, 1920, B. Annenkov moved to the city of Urumqi, settling in the former Russian Cossack barracks. At the same time, which is typical, the Russian colony of Urumqi did not meet the Annenkovites when they entered the town, remembering the monstrous atrocities they committed at the Selke Pass.

“Partisans” were forbidden to appear in the city and have any communication with the local Russian colony without special permission. In September 1920, B. Annenkov moved to the Gucheng fortress. In March 1921, B. was arrested by the Chinese authorities and sent to prison in the city of Urumqi.

According to Annenkov himself during the investigation, one of the reasons for his arrest was the desire of the Chinese authorities to obtain his valuables through extortion. An additional motive was the conflict over the reassignment by the Chinese governor of the Manchurian regiment, which consisted of Chinese citizens, which General Yang needed to strengthen his own positions.

At the same time, there are also documents in which the Chinese authorities directly accused Annenkov himself and his “volunteers” of robbery and repeatedly demanded that he, when he was still at large, stop such actions by his subordinates.

In February 1924, he was released through the efforts of the chief of staff of the detachment, General Major N.A. Denisov and thanks to the intervention of representatives of the Entente countries. On April 7, 1926, he was fraudulently captured by the commander of the 1st Chinese People's Army, Marshal Feng Yuxiang, and for a large monetary reward was handed over to security officers operating in China, after which he was taken to the USSR through Mongolia.

To hide the fact that Annenkov was extradited by the Chinese, a version was spread in the USSR about Annenkov’s voluntary crossing of the border and surrender to the Soviet authorities, as well as about his renunciation of his previous views, which was not true.

In the period from July 25 to August 12, 1927, a court hearing of the visiting session of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR was held in Semipalatinsk. The main point of the accusation is mass atrocities against prisoners and civilians; the number of victims of Annenkov’s terror is not even hundreds, but many thousands of victims.

Thus, based on the materials of the investigation into the crimes of Annenkov and his assistants, it was established that in the city of Sergiopol 800 people were shot, chopped up and hanged. The village of Troitskoye was burned, where Annenkovites beat to death 100 men, 13 women, 7 infants. In the village of Nikolskoye, 300 people were flogged, 30 were shot and five were hanged.

In the village of Znamenka, 45 versts from Semipalatinsk, almost the entire population was slaughtered; here women’s breasts were cut off. In the village of Kolpakovka, 733 people were chopped up, shot and hanged, in the village of Podgorny - 200.

The villages of Bolgarskoye, Konstantinovka, Nekrasovka were burned. In the village of Pokatilovka, half the inhabitants were hacked to death. In Karabulak, Ucharal volost, all the men were killed. According to witness Turchinov, the corpses were not buried, and the dogs were fattened to such an extent and became accustomed to human meat that, like beasts, they rushed at living people.

In addition to the atrocities against the civilian population, Annenkov was also accused of shooting the rebel Yarushin brigade that tried to go over to the Red side. The mass execution near Lake Alakol of 3,800 soldiers and Cossacks who wished to remain in Russia when the ataman’s corps fled to China was not considered in detail by the prosecution, since it became known in detail only after the verdict was passed. On August 25, 1927, B. Annenkov was shot along with N.A. Denisov.

On September 7, 1999, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation refused to rehabilitate B.V. Annenkov and N.A. Denisov. Maybe Annenkov was right that at some point the blood-drunk thugs became uncontrollable, carried out pogroms, robbed and killed without regard for their commander.

However, he, Annenkov, made them so. Paraphernalia made of a skull with human bones, rods, whips, illegal executions without trial or investigation, brutal executions - all this was imposed by the ataman himself, basically everything was done on his personal order and was carried out immediately, in his presence.

The bulk of the Semirechensk Cossacks remained in their homeland, having experienced the full brunt of de-Cossackization, evictions, executions and “land and water reforms.” Until the beginning of the 30s, rebel detachments were still operating in the Lepsinsky mountains, and in the town itself there was an underground White Guard organization led by Sushkov (destroyed by the security officers only in 1928).

And with that, the story of Bely Lepsinsk ended...

Authority and photos by:

General Cossack newspaper. "Stanitsa". A. Ushakov.

Lieutenant General of Justice D. M. Zaika, Colonel of Justice V. A. Bobrenev, Ph.D. (“Military History Journal” 1990 - 1991)