Вы здесь

History towns of Khuwara and Yangikent.

Monuments of culture of South Kazakhstan.

‘Why cannot the ancient town near Jankent be our local Pompeii?’

Stasov V.V.

History of ancient architecture of Kyzylorda region

The Oghuz and Turkmen tribes, the Seljuks played a very important role in the history of Eurasia1 . These tribes had lived on the territory of Kazakhstan in the period from the IXth to XIIth centuries and afterwards they moved to the South of the Central Asia, Iran, Afghanistan, South Caucasus and Asia Minor participating in the formation of the Turkmen, Azerbaijani and Turkish peoples. Large groups of the Oghuz intermingled with Kazakh, Uzbek, Karakalpak, Bashkir and Tatar ethnic groups.

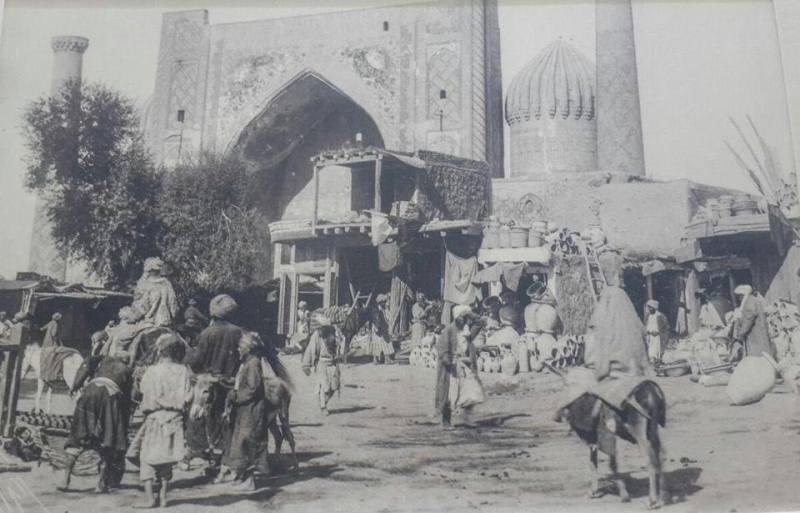

The remains of the town of Yangikent, the capital town of the Oghuz tribes is one of the best known elements of their cultural heritage known to archaeologists. Today it is known as the ancient town of Jankent, which is situated close to the Kazalinsk in the Aral Sea region.

This ancient town appealed to researchers for a long time. The famous orientalist Lerkh P.I. examined this town in 1868, the painter Vereschyagin V.V. conducted excavations there in 1868 and it was described by Kallaur V. and Smirnov V., the members of the Turkestan Union of Archaeology Admirers.

The interest of that society to antiquities of Kazakhstan and Central Asia was so great that in his review of the N. Simakov’s book The Art of Central Asia, the famous orientalist of that time Stassov V.V. wrote: ‘Why cannot the ancient town near Jankent be our local Pompeii?’.

Even then there were attempts to save the town from destruction. V. Stassov wrote: ‘… military people, who usually do not care about ancient heritage, are interested in ruins, think about their importance for science, choose guard to protect them and try to save them...from any harm...

It is perfect, isn't it? It is a great news for us. A lot of time passed since that time and in mid-XXth century or to be more exact, in 1945, the head of the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition of the USSR Academy of Science Sergey Tolstov began the exploration of the Oghuz towns in the Aral Sea region.

Areas populated by the Oghuz. The information contained in al-Idrisi’s Kitab Nuzhaty, works by al Istakhri, Marwazi and al-Biruni helps to define the borders of the areas inhabited by Oghuz tribes in the Xth century.

They lived in the steppes of Kazakhstan stretching from the Southern Balkhash to the lower reaches of the Volga river6 . They densely populated the Aral region, the Northern Caspian region and the lower reaches of the Syr-Darya river.

Separate groups of Oghuz lived in Zhetysu, where in the Xth century where the dominant local Turkic tribes were Karluks and Kimaks. In the 10th century one of the group of the Oghuz tribes moved to the valley of the Chu river in the Talas Alatau.

Idrisi calls Oghuz tribes living in the Shu valley ‘the khandag’. These Oghuz tribes were remarkable for their courage and independence. In the Xth century, some Oghuz tribes also inhabited the middle reaches of the Syr Darya river and the foothills of the Syr Darya Karatau.

The presence of the Oghuz tribes in the middle reaches of the Syr Darya is confirmed by other Arab sources of the Xth century. Ibn Hawqal says that the Oghuz lived at the edges of the desert, where the Shash river crossed the border of the Sabran area.

The Persian version of the Istakhri’s work contains some very interesting information about Oghuz’s settlement there. The works says: ‘Where the (Chach) goes beyond Sabran, along this river in the (territory of) Daruye one can find Oghuz settlements’.

The Oghuz nomads also stayed at the left bank of the Syr Darya and Istakhri says that the town of Syutkent was the frontier town of Transoxiana (Maverannahr) with the Turk-Oghuz population areas. The Oghuz tribes lived between Farab and Kendzhida, which situated at the middle reaches of the Arys river.

The town of Subaniket (Arsubaniket) became the main town of the region. In the Xth century a part of the Oghuz tribes lived within Shash and Isfidjab regions. The other part of these tribes lived in the Keles steppe, in the valley of Angren and Chirchik, in the foothills of the Chatkal and Urgan ridges.

In these places, the Oghuz tribes lived together with the Karluk and other Turkicspeaking groups. These tribes were partly subjected to Islamisation and partly settled in urban and rural areas of Shash and Isfidjab regions.

The Oghuz tribes lived both in the middle and the lower flow of the Syr Darya river. In the Xth century the majority of the Oghuz roamed across the steppes around the Aral and Caspian Seas. Al-Masudi noted that there were a lot of camps of the nomadic Oghuz in the steppes of the Caspian (Khazar) Sea.

Their camps could also be found to the west of the Aral Sea. Geographic atlases of the Xth century put Oghuz to the Northern and Eastern shores of the Caspian Sea. There is a Siyah Kuh mountain situated to the North of the Caspian Sea.

The book Khudud al-Alam mentions the settlement of the Oghuz Turks at the Siyah Kuh. Maps of al-Idrisi also point our camps of Oghuz at the Siyah Kuh. Several researchers identify the Siyah Kuh with the Mangistau peninsula.

According to Istakhri’s map and the works of Ibn Rustah, in the Xth century the Siyah Kuh referred both to the stony semi-deserts of the Mangistau and to the steep chinks of the Ustyurt Plateau. In the Xth century the western borders of the area where Oghuz built their camps and fortresses, reached the Southern Ural and Volga regions.

Additionally, Oghuz roamed along the Irgiz, the foothills of the Mugodzhar Hills, Emba, Ural, the banks of the Aralsor and Uil. In the Xth century the line of Oghuz camps stretched from the Ural to the lower reaches of Volga.

According to Khudud al-Alam, the Oghuz tribes reached Attil from the Northern part of the Caspian Sea: ‘the Eastern (part) of the region of (Oghuz links) to the Gus desert and towns of Transoxiana and the Southern part (links) to several (places) of this (Gus) desert.

The other (part of this region), borders with the Caspian Sea and the Attil river from the North and South.’ Settling of the Oghuz tribes in the lower reaches of the Volga river is also confirmed in the works of Istakhari and Ibn Hawqal.

The Oghuz tribes, who in the Xth century migrated along the Ural and the left bank of the Volga river, bordered with Bashkir and Burtas tribes. Lands of Oghuz bordered with Bashkir in the foothills of the Southern Ural.

Ibn Fadlan noted that the Bashkir tribes lived near the Bagnadi river, which probably coincides with the modern Yavynda. He writes about the Bashkir pillaging caravans which passed through the Oghuz lands and went on to Volga Bulgaria. In the Xth century the Western Oghuz tribes had common borders with Bashkir, Khazar and Burtas, who lived in the Volga region.

Oghuz towns. Idrisi described Oghuz towns as ‘numerous and situated in line from the North to the East. They have constructed their fortresses in the impassable mountains and these fortresses are hiding their princes and food supplies.

There are people (appointed princes) who guard this land ... their main town (the Handaga(s) tribe of the Oghuz) is called Khiam. This fortress gives them shelter, where they can hide with their belongings. It is situated on top of the mountain with the difficult climb, which is difficult to reach.

The fortress is well defended. The towns of Khiam from the north and Dzhadzhan from the south of the river are small, highly fortified and similar. On the bank of this river (Magra or Marga) there is a mountain with the high peak, which gives the beginning to thousands of springs, which then flow into the Magra river.

There are two fortresses-towns at the top of the mountain called Nudjah and Badagah, which are situated in a one day journey from each other... There are the towns of Daranda and Darku on the foothills of mountains mentioned above. Daranda is situated to the West from Darku and there are 3 days of journey between them.

These are two small towns, which have markets, artisans and high-class goods. Both towns are well-fortified and unassailable. There is always snowy weather in these towns and that is why their residents are gather raw crops and dry them with the help of smoke under shelter.

It is always cold and rainy there and very few dry days in a year...’ Then follows a description of the town of Gorguz (large fortress situated in the mountain near the lake with the same name), Dzhardzhan and ‘Dakhlan town, which is similar to a fortress’.

The chieftain of this settlement ‘has necessary ammunition and army and invades Taraz from time to time...’ The book also mentions such towns as Ruzan, Rudan and Garbian and ‘the ancient town of the Oghuz’.

Mahmud al-Kashgari names such Oghuz towns as Sauran, Karachuk, Sygnak, Syutkent and Karnak. He maintains that ‘the group of Oghuz, living in these towns, which does not move to other towns and which does not fight, is called Yatuk’.

In the lower reaches of the Syr Darya, the Oghuz tribes were living in towns of Djent, Yangikent and Khora. The group of Oghuz tribes also lived between Farab and Kendzhida. The part of Oghuz tribes lived near Shash and Isfidjab. Al-Maksidi tells his readers about the Turkmen tribes living in Beruket and Baladzh.

There are some other indications that the Oghuz never lived in towns at all. Thus, in the essays of the anonymous author of Khdud al-Alam it is written that the ‘Oghuz tribes do not own towns, but they are a people which has felted yurts and is quite numerous’.

Trying to reconcile such controversial data, Vladimir Bartold maintained that Oghuz towns had been founded not by the Oghuz, who were mainly nomads but by other peoples, including the Khoresmians and then also inhabited by the part of the Oghuz who settled there.

Sergey Tolstov was more specific about this issue. He believed that the economy of the tribes of the Ural region, including Oghuz tribes, was complex and together with nomadic lifestyle, they were developing agriculture and urban life15. This point of view shared by several other researchers.

Karl Baipakov assumes that ‘Oghuz towns’ emerged and developed before the Oghuz and Turkmen tribes arrived there and it is only possible to talk about the Oghuz period of existence of these towns and the time when these tribes ruled these towns and some of these tribes turned to sedentary way of life and settled in the towns.

Towns of Oghuz in the Aral region. Describing the Oghuz tribes, the Kitab Rujar talks about Old and New Ghuzia. Al-Idrisi wrote that the distance between Khiyam and Old Ghuzia is four days’ journey from the South to the West.

Old Ghuzia is located in the area limited by the Western branches of the Tian Shan, the Shu river and the Syr Darya Karatau. It is believed that the term Old Ghuzia refers to the old capital ‘town’ of the Oghuz tribes. It is obvious that it was the one of the first residencies of the Oghuz rulers.

Idrisi also mentions New Ghuzia while describing lower reaches of the Shash river (Syr-Darya). New Ghuzia, being the political centre of the Oghuz tribes, was the winter residence of a ruler. New Ghuzia is the name given to the town of Yangikent, which was located in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya river.

Persian and Arab sources also call Yangikent the New Town, al-Karyat, Al-Hadisa, Dih-i-Nau and Shehrkent. The genesis of these names is probably connected with the fact that the Oghuz tribes established political hegemony in the Syr Darya steppes.

The distance between Yangikent and Khoresm was a 10 days’ journey and between Yangikent and Farab, a 20 days’ journey. Yangikent imported bread from Transoxiana (Maverannahr) along the Syr Darya. One of the first mentions of Yangikent in the Arab sources can be seen in Ibn Rustah’s works.

Describing the eastern bank of the Khoresm lake, he mentions ‘the ruler’ of the New Village. Ibn Hawqal presents very interesting facts about Yangikent. In his historical and geographic work he holds that the New Village is the new capital town of the Oghuz state. According to him, Yangikent was the largest town in the lower reaches of Syr Darya.

The choice of the New Ghuzia as the political centre of the Oghuz power was presupposed by such events as beneficial geographic location of Yangikent at the border with large agricultural centres and oases of Kazakhstan and Central Asia and the fact that New Ghuzia was the corridor, which linked the Oghuz steppes with Khoresm, Transoxiana, and Khorasan.

Yangikent was situated at the important caravan route through the Kimak steppes to the valley of Sarysu, Kengir, Ishim and Nura. The road linked with trade routes leading to Sygnak and South Ural. According to the written sources, Yangikent was conquered by the Mongol army led by Jochi.

Unlike Sygnak, Anshas and Barchkent, whose residents tried to resist to Mongol army and were destroyed, Yangikent was surrendered by its citizens without fight and thereby avoided demolition and violence. According to the written sources, there was the town of Khuvara (Dzhuvara, Khora) located near Yangikent.

If there is a clear indication about the precise location of Yangikent, there are some difficulties and controversies related to the attempts at defining the location of Khuvara (Dzhuvara, Khora). Some time ago Karl Baipakov apparently maintained that it had been situated near the Korkut Ata mausoleum.

However, by now his opinion has changed – this town corresponds to one of the ‘marsh settlements’, either Kesken Kyukkala, or Kyukkala, more likely the former. These are remains of a large town with the complex topography, great amount of material, which shows that the town existed in the period from the 1st century AD until the XIth century AD.

Interestingly, Ammianus Marcellinus mentioned the town of Khuvara as the town of Khavrana in the late IVth century. Additionally, he talks about towns of Aspabota and Spaga, situated at the Lower Syr Darya. Sergey Tolstov believed that marsh towns existed since the ancient time until Xth - XIIth centuries.

The overwhelming majority of ceramic items found there is rough and thick, made without potter's wheel and unevenly baked. The ceramic is of reddish, yellow and dark colours and its surface is covered with rich ornament. The entire collection of ceramic items can be subdivided into two main typological groups.

The fragments involve mouths with bent and flattened edge at the top, surrounded by a lip, decorated with herringbone, vertical oval and linear stamp mark and bundles. There are also poorly baked vessels, such as pots and bowls, decorated with rich ornament.

The ornament is presented by the lavish curved spiral and floral design with segments of coil and leaf patterns are dominant. The researcher came to a conclusion that the ‘marsh towns’, which are situated in lower reaches of the Syr Darya, appeared in the first centuries AD and were created by local population.

Khoresm and the Dzhetyasar culture influenced the establishment of the urban culture. In the X - XIIth centuries these towns are gradually becoming Oghuz towns and constitute the urban component in the mixed cattle breeding-agricultural and fishing economy of ancient Turkic tribes, who created a unique form of urban culture.

L.M. Levina, who analysed the complex of ceramic and metal items of Kesken Kuyukkala, Large Kuyukkala and Jankent, received from excavations, came to some interesting conclusions. The majority of ceramic items are created without the use of the potter's wheel, of poorly mixed and precipitated clay of uneven firing.

Based on the quality and the character of firing, the majority of vessels for storage and transportation of water and grain and a part of socalled ‘table’ ceramics is difficult to distinguish from the ‘kitchen’ ceramics. Usually, the mouth is decorated with curved and intended pattern forming straight and miter incisions, parallel rows and zigzag cuts, horizontal and vertical herringbones as well as symmetric sub-triangle and sub-square sticks.

Such mouths, their form and decoration with grey or brownish engobe and polishing, with miter and straight incisions on the surface, impressions and symmetric sticks are peculiar for the Dzhetyasar ceramic beginning from the Dzhetyasar-2 stage.

The patterns at the mouth placed along a zigzag line, horizontal herringbone and sticks with incisions are peculiar to the monuments of the Dzhetyasar-3 stage. Usually, such moulded roller with incisions is combined with cut-in herringbone ornament over the mouth or below it.

In general, various combinations of vertical and horizontal herringbone ornaments at the small, subtriangle in cross-section, mouth and below are peculiar for the ceramics of the Kesken-Kuyukkala complex. These vessels usually have moulded relief at mouths and the body (below slanting shoulders) has continuous series of pits or very rich and diverse cut-in floral ornament depicting various combinations of lines, leaves and petals.

Sometimes these patterns are shaded with parallel lines, panes, impressions and notches. Such ornament is peculiar to vessels with bloated body and jugs with a spout. Archaeologists have found truncated conical cups at the excavations of the Kesken Kuyukkala ancient town.

There were also cylindrical cups, covered with light red engobe and polishing similar to those founded at some Dzhetyasar ancient towns. During excavations of the Kesken Kuyukkala complex, archaeologists have also found a fragment of mounted table (35 cm in diameter), made of red clay and covered with reddish engobe.

Some of these fragments do not have any decoration at all and others are decorated with finger marks from its inner side and a moulded roller with pin-tucks from outside. The majority of covers are decorated with rich cut-in floral or geometric ornaments and others had rest-protuberance.

Such covers with the ornament mentioned above are peculiar to monuments of the Zhetysu of the VII - Xth centuries. It is possible to find such covers in Middle Syr Darya at excavations of ancient towns of Otrar and Karatau foothills of the VIII - Xth centuries.

hese covers are also peculiar to the monuments of the Dzhetyasar-3 stage. It's worth noting the unique character of cassolettes and lamps, which were found at marsh towns of Kesken Kuyukkala and Kuyukkala. Their form, character and size are similar to those, mentioned in the archaeological reports of the ‘Big House’ of the Dzhetyasar-3 period.

There are lamps with opened tank-cup, blackened inside and with thick cone support. Cassolettes are decorated with miters and impressions made with the help of a stick for firing. Similar lamps with a high pallet and a tank-cup at the top (sometimes decorated with scallops of its edge) have three supports and are often decorated with cut-in herringbone incisions.

During the excavations of the Kesken Kuyukkala ancient town, archaeologists collected Turgesh, Tan, BuharHudat coins, plaques, toppers and clasps. It means that the culture of marsh towns is based in the Dzhetyasar culture, which was influenced by the culture of Zhetysu, the Middle Syr Darya and Khoresm.

New materials about the Oghuz marsh towns were obtained from the excavations of the Jankent ancient town, conducted by researchers from the Margulan Institute of Archaeology (Ministry of Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan), the Korkut-Ata Kyzylorda State University and the Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of Russian Academy of Science.

The high degree of neglect and desertion of the ancient town is vividly verified by numerous burials, presumably dated back to the XVII - XIXth centuries. The second level has vanished and there are traces of constructions. The central part of the citadel has been subject to intensive denudation processes.

The construction situated closer to the outer wall had been preserved better. The third layer contains the remains of buildings and streets. It is obvious that the streets existed there for the duration of at least two construction horizons and even longer.

Apparently, construction horizons repeat each other. The excavated construction horizon may be dated back to the X - XIIth centuries. During the excavations archaeologists identified the street of a citadel and premises built on both sides of the street.

At these premises archaeologists found rectangular and round fireplaces, fragments of ceramics, bones of domestic animals and metal items. While removing and cleaning of fill-ins in the premise №16б archaeologists found vessels and a terra-cotta bird near them.

Additionally, during the excavations and cleaning of premises, the traces of ash and charred wood were found. In the layer of ash and charcoal, they have found fragments of ceramic vessels, covered the surface of sufas, a terracotta cassolette covered with river floral patterns, and a fragment of a bronze bracelet.

The premise excavated in the North-Western part of the ancient town has a fireplace with a vessel pitched nearby. One of the premises of the residential had a unique altar decorated with sheep protoma covered with curving.

The outer part of the altar is surrounded by charred planks with remains of a curved ornament. All premises are grouped in separate households. One of the houses occupied the territory of 280 square metres and the total area of excavation covers seven houses.

The Archaeological Expertise LLC has been working at the excavation of Kuyuk-Keskenkala ancient town since 2006. As the result, the expedition collected huge material, including coins, ceramic, beads and bronze jewellery.

The topographic plan of the territory of the ancient town as well as the study of cosmic and aerial photos of the site allowed scholars to identify the structure of the monument. A regular and systemic exploration of the ancient town began in 2007.

The Kesken Kuyuk-kala is the largest of all ‘marsh’ towns. The ancient town, which represents irregular oval 830 х 710m in size, rises 2m above the surrounding terrain and consists of a shakhristan, citadel and two rabads. The ancient town was surrounded by a wall, which preserved the height of about 2 metres.

The North-Eastern part of the town has a 210 x 210 hill of a shakhristan rising 3m above the level of the ancient town. The shakhristan is divided by a 3-metre diagonal street with passed going to different directions and dividing the territory of the citadel into buildings of different size.

At the southwestern corner of the shakhristan there was a citadel, rising 1m above the shakhristan, its square being 60x60m. The shakhristan is linked with the first rabad from the South, South-West and West and it is separated from the second rabad by the wall.

The second rabad is situated to the East and South-East from the shakhristan. The plot of land of the ancient town in size of 21 x 63m was chosen as an object of research. This plot of land is situated in the Eastern part of the shakhristan and features the researched complex, decoded at aerial photos with the help of two intersecting streets.

The surface of the plot of land has traces of walls of premises and there are a lot of ceramics and bones. Archaeologists have partly or completely explored 37 premises, which is the larger part of the complex. The stratigraphy of the excavation is represented by two layers:

The first is the destroyed layer of loose loamy grey and brown soil, interspersed with fragments of broken and burnt adobe bricks. The layer thickness is uneven and varies from 5 to 20 cm. The layer has traces of ash and charcoal.

There are a lot of bones of animals, fragments of kitchen implements as well as large and small fragments of moulded and mounted ceramics. The layer was subject to constant erosion by wind and water. The second layer has the remains of buildings and constructions made of rectangular and square adobe bricks.

The investigated layer is characterised by the obstruction of adobe bricks of fallen walls, which covered the area of the premises. In the process of cleaning of the surface of the floor and the pile of bricks, the layer of grey and brown and black ash, small particles of charcoal mixed with crashed adobe bricks was found in all the rooms of the site.

Layers of ash contain the bones of domestic animals and the fragments of moulded and mounted ceramics made of red and grey clay. The North-West part of the complex has a rectangular ‘templar’ room, stretched from the North to the South and 11.3 x 8.5 m in size.

The temple occupies the area of 100 square metres. The vault of the temple rested on columns, rectangular in cross-section and made of adobe bricks. The columns were 29 x 29 x 6 cm in size and their bases have been found while cleaning the premise.

Room 6, 6 х 4.2 metres in size, consisted of 2 rooms, one 1.8 х 4.17 m and another 2.1 х 4.17 metres. In the room 2 archaeologists found and cleaned a number of ceramic vessels, including fragments of a pot, moulded black ceramic cassolette, which reminds a toe in its shape.

During cleaning of an obstruction in the room 1, researchers found a fragment of a pan under the wall from the eastern side. At the floor they have found a bone plate of a bow made of a long bone of a large animal. The cover plate is wide in its bottom and gently tapers to the top and then bends.

The top of the cover plate is decorated with a curving, which reminds small protrusions to attach strings. The centre of the cover plate has four holed for attaching strings. The outer surface is both polished and smoothed. The length of the cover plate is 21 cm, the lower part is 5 cm in width and the upper part is 1.8 cm in width.

There is also an iron triangular stemmed arrowhead, which is 6.3 cm in length. The size of the top of the bow is 3.4 x 1.7 and the size of the stem of the bow is 2.9 x 0.8 cm. The premises with altars on the floor are very interesting, since they have two moulded columns with protomas decorated with sheep heads.

For example, in Room 15, which is rectangular in its shape and is 7.2 х 5.8 m in size, researchers cleaned the U-shaped sufa, which goes along the walls from Western, Eastern and Southern sides. The sufa is 1.08 cm in size and its height from the floor is 0.55 m.

The sufas, situated along the Northern and Southern parts are 2.8 m in height and the width of benches varies from 0.55 to 0.57 metres. At the Western part they have cleaned the vessel let-in the sufa and standing at the edge of this sufa.

The vessel was mounted in the sufa. The vessel was filled with ash and small wood charcoal pieces. Apparently, the vessel was used for the storage of ash or as a cassolette. At the floor of the premise archaeologists cleaned the altar, which features a rectangular clay area, limited by ledges, the upper part of which are bent outwards.

The area of the altar is covered with grey and black ash and there is a red burnt spot covered with this ash. The altar is 1.1x0.8-0.85 m in size, the width of ledges is 0.1-0.4 m and they are 0.08 m in height. There were two fragments of sheep protomas at the Western part of the altar.

Their upper part was destroyed. In the centre of Room 21 archaeologists cleaned the altar with decorative floor covering, which depicts the head and horns of a sheep. The altar was located on the dense adobe floor between U-shaped sufa and the southern wall of the premise.

The altar features an area made of grey sub-rectangular loan, decorated with ledges placed over the perimeter. The coating is 2.5 cm in width. Its surface is covered with the layer of ash and a calcined light brown spot. At the centre of the altar researchers found a ceramic cup with a vertical loop-shaped handle.

The large Room 29 with the altar needs special attention. The northern wall of this room has the ledge of the sufa made of adobe bricks. Its edge is covered with the mud plaster. The ledge of the sufa was connected with the wall of the earlier construction level. The wall was partly destroyed and dismantled.

The face of the wall and the sufa are connected with the partition wall with niches. At the southern part of the room archaeologists cleaned the wall dated to the late construction period, which was built on the rubble of bricks. The bloc of bricks and the wall built on this bloc, covered the southern side of the floor altar.

The wall of the latest construction period separates the territory of the altar from Room 34, which has a sufa. Before reconstruction, Room 34 was part of the premise with the altar. The centre of Room 29 had a floor altar. The area of the premise around the altar was covered with ash a small wood charcoal as well as debris adobes.

he floor of the room with the altar was partly damaged by the walls, fallen inside. The altar represents a sub-rectangular area, bounded by the straight ledges, moulded together and made of well-precipitated clay. There are shoulders on its edges.

The inner part of the altar looked like a surface coated with the 2.5 thick clay solution. Insides of the altar had a layer of ash and light brown calcined spot. At the centre of the altar was found a ceramic cup with a vertical loopshaped handle. The area at the western part of the altar had a sheep protoma, made of dense clay.

The protoma has a form of an inverted truncated pyramid, 40 cm in height, 28 - 33 cm in width and 21 cm in thickness. All buildings of the complex can be divided into two kinds, rooms and premises. It is assumed that the ceiling of the complex was flat, rested on the wall and in large premises it was supported by adobe or wooden pillars.

The ceiling was covered with the thatched roof with its remains found on the wall, and walls were carefully plastered with clay coating. In the majority of premises the waterproof clay coating of floors has been preserved. Some rooms were full of ceramic fragments.

In the centres of six rooms archaeologists have found altars. In general, rooms with altar are characterised by the presence of sufas (four rooms), different vessels (four rooms), all altars were oriented to the cardinal points (two of them oriented from the West to the East and four from the North to the South).

The adobe floor alta f them were created by moulding of well-mixed clay. The upper part of the altar had vertical sheep protomas, decorated with floral ornament similar to the ornament of the ceramic vessels found during excavations. rs were made with the help of moulding of well-mixed clay.

The construction of the altars was very similar. All of them are rectangular in shape; there were ledges with and without shoulders and all Protomas were mounted at trapezoidal columns, which were probably decorated with some ornaments.

Core lenses, ash and remains of coal prove that there was a fireplace. The interior of the altar was carefully plastered with clay. The inside of the altar has a lot of ritual vessels in the form of not ornamented cups. In two cases there are extra details such as curved adobe lying at the floor.

Ceramic items are one of the most numerous categories of findings at the Kuyuk-kala ancient town. The ceramic complex is divided into moulded ceramic and ceramic made at the potter's wheel. The moulded tableware is most often made of red clay but there are also items made of grey clay.

The list of admixtures involves sand, mica, chamotte, limestone, quartz and gypsum. The major part of the tableware has been well fired and baked. The moulded tableware includes pots, cups, kettles, jugs, vessels, covers and tables. The tableware is decorated with floral and geometric ornament.

There are stylised zoomorphic necks and handles. The major part of the ceramic vessels is covered with red, reddish, brown, light and dark engobe. Some vessels have been polished. All tableware items are made on the potter's wheel of well-mixed red clay.

There are mixtures of sand, mica, gypsum and chamotte. Tableware is presented by jags, which are decorated with curved floral and geometric ornament. Pottery is also decorated with red, light red, violet, purple and light drips. Spindle whorls and protomas are a separate category of ceramic items.

Spindle whorls are usually disk-shaped items with open-end holes. Some of them have engobe glaze and traces of attrition from the use. One spindle whorl was made of a crock of a large clay jar. Two ceramic ‘toes’, decorated with carved floral ornaments are particularly interesting.

Apparently, these ‘toes’ were used as cassolettes. The upper level of excavations also has fragments of tableware with transparent glaze over the white engobe. Additionally, during the excavations of the Kesken Kuyuk-kala ancient town archaeologists have found Turgesh, Tan and Bukhar-Hudat coins.

The coins of the Afrigid Khoresm of the 7-8th centuries, which proves the connection of marsh towns with Khorezm, are among the most valuable findings. Archaeologists also found numerous jewellery items, including a massive bronze finger ring with inserts made of lasurite, fragments of lasurite charms, bronze earrings, rings, bracelets, bronze details of clothing and elements of horse harness, including plaques (round, heart-shaped, rectangular, five and six-cornered as well as laced), caps for belts, buttons, pendants, bells, clips, belt buckles.

It is interesting to note the finding of the bronze statuette of a horse. Archaeologists managed to find a large collection of beads made of glass and semi-precious stones. There are also fragments of stone grain mills, pestles and grinding stones.

Additionally, it is interesting to note the finding of a gem, featuring a face of a girl and a bird. The inscription bylpyk y wyhdyn, is made in the ancient Pehveli and means ‘Bilbig the Blessed’. The gem dates back to the IV - Vth centuries.

Another version of the translation of the inscription at the gem is Farn-baga Vohu Dena or ‘happy master’, which can be the name of a man and ‘virtuous religion’, which is the name of a goddess. Metal items were presented by fragments of knives, stirrups, bits, nails and fragments of locks.

Based on the dating of ceramic material, data of radiocarbon analysis, it is possible to date the upper level back to late XII- early XIIIth century and the second level to the X - XIth century. The ancient town was abandoned in the 13th century.

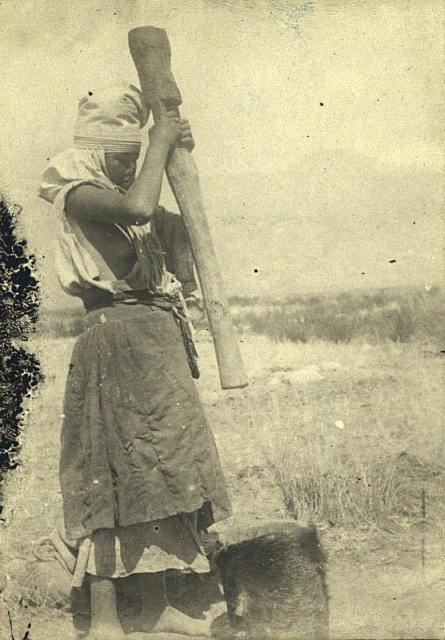

The materials found during the excavations have allowed scholars to reach certain conclusions about the economy of the residents of Kesken Kuyukkala. Sergey Tolstov describes the economy of the Oghuz tribes which lived in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya as a complex way of life involving cattle breeding, agriculture and fishing.

The presence of a great number of bones of domestic animals found in cultural layers proves the presence of well-developed cattle breeding practices. The residents of the ancient towns bred camels, goats, sheep, horses and cows.

Carpological studies, conducted by S.V. Bashtannik, proved the high level of development of agriculture. The residents of Kesken Kuyukkala were familiar with such crops as Hordeum vulgare distichum double-row barley, Triticum aestivum soft wheat and possibly, with the legumes.

The connection of the settlements to swampy deltaic ducts (hence the notion of ‘marsh towns’) and the findings of fish scales and bones testify to the importance of fishing for the residents. The materials obtained during the excavation works at Kesken Kuyukkala, only confirm significant development of pottery, glass making, iron and brass casting production specific to the ancient towns.

In most cases, the ‘towns of the Oghuz’ on the Syr Darya emerged and developed long before the arrival of the Oghuz and Turkmen at this territory. Today it is possible to identify and discuss the Oghuz period of their existence and the time of the political domination of the Oghuz on the territory.

These towns were ruled by the Oghuz, who had their governors and kept their treasury in these towns. Yangikent and Huwara were new and old capital towns of the Oghuz, and the old capital, the town of Huwara is most likely located at the Kesken Kuyukkala archaeological site.

Part of the Oghuz and Turkmen started to live in towns and later became assimilated with the urban population by adopting the urban lifestyle and culture as well as the urban household practices. However, they preserved their ethnic specificity in the production, especially of domestic ceramics, part of which was used for religious rituals associated with food preparation.

Considering the issue of ‘the Oghuz towns’, it is worth noting the typical ethnic and political context that dates back to the era of Kanguy, in the Syr Darya basin. This includes the ‘nomadic’ nature of the state, described in some written sources on the one hand, and the presence of the developed sedentary urban culture, evident from the available archaeological material, on the other.

The next stage is connected with the early Medieval Age, when Kangu Tarban, an independent Turkic state appeared on the Middle Syr Darya. Kangu Tarban was founded as a symbiosis of the military and political assembly of the Pecheneg with the sedentary urban population.

The role of the Kangar in the establishment of Oghuz and then Kipchak tribal unions was quite significant. Later, in the X - XIth centuries, the foothills of the Karatau at the Syr Darya witnessed the establishment of the state of nomadic and semi-nomadic Oghuz and Turkmen tribes with urban population, who have already adopted Islam but retained some of the traditions of pre-Islamic religions.

The Oghuz state, the Oghuz and Turkmen tribes played a significant role in the history of Eurasia, in the political, economic and cultural life of the states on the territory of Kazakhstan, Central Asia, Middle and Far East, South Caucasus, Asia Minor and Eastern Europe.

Therefore the issue of ‘Oghuz towns’ of is a part of the more global theme, "The Town and the Steppe".

Authoroty:

2012 K.M. Baypakov, D.A. Voyakin, R.V. Ilyin Almaty, Kazakhstan. http://www.unesco-iicas.org

Photos by

Alexander Petrov.