Вы здесь

Humboldt in Kazakhstan.

Tours and hiking to East Kazakhstan.

"We do not cease to turn our eyes to Asia, a trip in which takes, like a seductive dream"

Trips in East Kazakhstan.

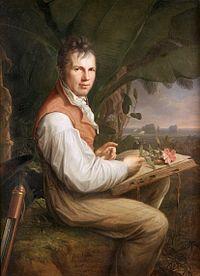

Each of the fields of science has its own recognized luminaries. In biology, this is K. Linney and C. Darwin, in physics - Newton and Einstein. In geography, the authority recognized throughout the world is Alexander Humboldt, a German scientist who became famous not only for his travels, but also for his special approach to issues of geography.

He was a pioneer in the scientific study of the earth, and from studying individual details he went on to generalize and analyze. He outlined new ways of studying the earth and laid the foundation for new fields of science, such as volcanology, the doctrine of terrestrial magnetism, plant geography, and others.

Humboldt wrote a huge number of scientific and popular books, which were read throughout Europe. His legends of South America, covered in legends, completed in 1799 - 1805 and described in the 30-volume edition, were universally recognized and created him world fame.

The name of the scientist during his lifetime was assigned to various geographical objects: rivers, lakes, bays, ridges and peaks. Many states would consider it an honor to have a guest as a great natural scientist. He was invited by kings and kings of different countries.

The compatriots reproached Humboldt for the fact that he had not lived in his homeland for almost thirty years. But as soon as he settled in Germany in 1827, he was invited to make a trip to Siberia. He was called to Russia before, back in 1808, but then the war with Napoleon prevented him. Now there were no obstacles.

In addition, the great master, who traveled to many countries, had long dreamed of a trip to Asia. Even earlier, he wrote: "We do not stop turning our eyes to Asia, the trip to which takes like a seductive dream." And in a letter to the Russian mining engineer V. Soimonov, who is going to Siberia, he admits: "How I envy your fate! What a happy opportunity to see the great creations of nature!"

Surprisingly, enlightened Europe knew Asia worse than Africa and Australia. Such a large area as Central Asia remained almost unknown to science. Mysterious Dzungaria, Kashgar, Bukharia under the brutal rule of medieval regimes did not allow foreigners into their possessions.

The available information on geography in these lands was reduced to the works of the ancient Chinese, Herodotus and fragmentary reports of the Venetian Marco Polo, who had been there since the Middle Ages. Now Humboldt had the opportunity to personally see Asia and test the theories he developed on the geography of this greatest continent.

Humboldt was already 60 years old. On an expedition funded by the Russian government, he took with him two professors from the University of Berlin, the famous mineralogist Gustav Rosa and the natural biologist Christian Ehrenberg. April 19 (May 1 in the new style) in 1829 they arrived in St. Petersburg.

The expedition has begun. Her route passed through Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Tobolsk. But how unlikely this trip was to the one that Humboldt made in his young years! Then, together with the Frenchman Aime Bonplan, they made their way through the jungles of South America, rafted along the Orinoco, climbed the snowy peaks, conquered volcanoes.

The journey was full of adventure and danger, and all this went on for five whole years. Now, especially for the trip of Humboldt and his companions, huge horse-drawn carriages were built - one in six horses, the other in four. In addition, three horses were intended for accompanying officials and two for couriers.

The glory and traditional Russian service of honor interfered. After all, Humboldt was a guest of the king himself, and therefore he was accepted as a very important person. The authorities warned him of his arrival in advance.

The officials were zealous, trying to outdo each other. Arranged solemn meetings, receptions, feasts with speeches and toasts. Humboldt tolerated indulgently, trying not to express his displeasure and irritation. He was a scientist, not accustomed to wasting time and certainly not a salon sharkun.

After a four-day stay in Barnaul, the expedition traveled to the factories of the Altai mountain district, visiting the Zmeinogorsk mine and the Kolyvan grinding factory that produces magnificent stone vases and various ornaments. Travelers drove through villages (Shemonaikha, Vydriha, Losikh, Ubinsk, Bystrukha, Cheremshanka), settled by immigrants from different parts of Siberia and Central Russia, among which stood out the so-called "Poles" - Old Believers brought here from the western provinces of Russia.

The peasants lived neatly, and many of them prosperously, having livestock, apiaries and engaged in tillage. In addition to the official authorities, who greeted the German guests with military reports, crowds of people gathered everywhere to take a look at the overseas guests

The mountainous terrain required a lot of effort to ride, so harnessed to heavy crews 10 horses. After the Cheremshanka, the road, still looping along grassy planks, went along the mountains overgrown with forest. Ulba was noisy nearby, the wheels were stuck in loose soil.

Having taken the last, especially steep climb up the hill, at 7 o’clock in the evening the crews drove into a vast green valley surrounded on all sides by mountains, and the highest was Ivanovsky Squirrel. There were two mines here: Riddersky, opened in 1786, and Kryukovsky, opened later.

The local ores were rich in copper, gold, lead and silver. Like most scientists of that time, A. Humboldt was an encyclopedist, besides geography he was interested in a lot: mining, mineralogy, botany, economics, history.

All day, visiting scientists, accompanied by local experts, walked through the underground workings, inspecting the faces, dumps of ore, mine structures and were so busy all day that they could only have lunch at 10 in the evening. For a lodging for the night, they took a house from the windows of which overlooked Ivanovsky Squirrel, with a foot located just a few miles. All of it was overgrown with forest, and at the top there were white spots of snow.

The next day was devoted to visiting the Kryukovsky mine. Geologist Menshenin showed the guests a crowd and a washroom for gold, and in the afternoon Ehrenberg, accompanied by the same Menshenin, went on an excursion to the mountains.

For two versts they heard the sound of the Gromotukha River, the gorge of which was separated by two mountain ranges: Ivanovsky and Prokhodny. On a steep path, winding through a dense forest, travelers climbed to the top of Passing Squirrel, where Ehrenberg collected a collection of plants and minerals.

Humboldt, an adherent of the theory of volcanism in Central Asia, sought confirmation of it in Altai. In the Ulba valley below Riddersk, he drew attention to a cone-shaped hill, where he made an excursion, concluding that it was composed of volcanic rock, and at the same time drew attention to the lush vegetation.

“This mountain is striking in its rounded shape. The view of the rock and the large amount of transparent quartz contained in it convinced us immediately that the Kruglyaya Sopka consists of trachyte (trachyte - volcanic rock - A.L.).

We climbed to its top, but hardly paved our way between the grasses covering it, which the gigantic development characterizes many North Asian steppes; no less than the uniform forest vegetation characterizes the warm zone of South America. "The flowering grasses of the surroundings of Krugly Sopka overshadowed our heads and reached 9 feet in height (2.7 meters - A.L.)."

The scientist was clearly mistaken, wishful thinking and even G. Rosa, who accompanied him, recognized the breed not as trachy, but only similar to it, which was later confirmed by other scientists. How tight the expedition schedule was can be judged by the fact that on August 13, travelers arrived in Ust-Kamenogorsk at 4 a.m.

The town did not make an impression and consisted of only a few streets with small one-story houses. The city grew near the fortress, where there was a military garrison, and the commandant was Colonel Liancourt, a Frenchman by nationality.

Although he lived in Siberia for 39 years and could tell many interesting things, Humboldt was much more interested in the Russian industrialist and experienced man S. Popov, who traveled to Kashgar and Tashkent with goods caravans and came to Ust-Kamenogorsk specifically to meet with the world famous scientists.

The wealthy Semipalatinsk breeder Stepan Ivanovich was interested in scientific achievements, made acquaintances with all visiting scientists, and besides, he wanted to show his establishment with the vain idea that he would be known in enlightened Europe.

A rich dinner was arranged for the German guests in the house of the Ust-Kamenogorsk merchant 2 of the Nakoryakov guild, during which they promised to visit S. Popov’s estate in Semipalatinsk. In the program of acquaintance with the Altai factories, which were considered the personal property of the king, the last was the most remote mine Zyryanovsky.

It was possible to get there in two ways: by water along the Irtysh in boats or by land along a heavy mountain road. Considering that the waterway would take a lot of time, we chose the land one, and, given its difficulties, the heavy crews were replaced by light Cossack shakes.

The road to Zyryanovsk for more than 150 versts goes either through narrow gorges overgrown with fir and aspen forests, or then climbs up steep hills. Even unpretentious Cossack shakes hardly made their way along a narrow, poorly arranged road, but travelers, although they did not see the snowy mountains, could make an idea of the vegetation of the Altai foothills.

Humboldt was no longer engaged in collecting collection material and direct measurements, this was done by his scientific satellites. He himself mostly looked, comprehended, comparing with what he had built in his imagination and his books before the trip.

It was difficult for him to abandon the theory of volcanism of Central Asia put forward by him. It was not confirmed - it was obvious. In vain he gazed with hope at the contours of the surrounding mountains, trying to find volcanoes in them.

By their outlines, many of them really had almost regular cones. Near the Bukhtarma fortress, a stand-alone slide attracted the attention of Humboldt. He wrote: “I was especially struck by the conical shape of a granite hill, located two miles from Bukhtarminsk and rising among the plains.

The Kirghiz call it “Bery-Tau”, and the Russians call it “Shaggy Hill”. By the way, almost all travelers who visited the Bukhtarma Territory in the 19th century noted this low slide in their notes. Such as Spassky, Ledebur, Bunge, Schurovsky. M. Muravyov-Apostol, the Decembrist who served the exile in 1829-1836, also liked to be there.

She now stands on the shore of the reservoir near the cement village of New Bukhtarma. This legendary slide deserved to be taken under protection and a memorial sign was installed, for example, a stele with the names of famous people who visited it.

Turning sharply to the northeast and now moving along Bukhtarma, six miles from the village of Talovka, travelers visited the Zavodinsky mine, where they described rare and nowhere else found ore minerals: hessite (tellurium silver) and altaite (tellurous lead).

At one o’clock on the night of August 4 (16), Humboldt and his companions arrived in Zyryanovsk and already in the morning began to get acquainted with mining operations. The village of Zyryanovsky mine totaled only 37 years since its founding, it was located in a hollow between low treeless mountains, already covered with yellowness of autumn wilting, and was not much different from an ordinary village.

Only wooden pile drivers of mines and ore dumps betrayed the presence of a mine here. Altai plants by this time became the main center of non-ferrous metallurgy in Russia, and the Zyryanovsky mine was considered the richest and, according to reserves estimates, contained more than 13 thousand pounds of silver in its bowels.

Silver mining amounted to more than 500 pounds per year, and the number of workers reached 700. A great inconvenience, greatly increasing the cost of metal production from Zyryanovsky ores, was the remoteness of the mine. It was not possible to organize metal smelting on site, so ore was transported for almost 500 miles to other smelting plants.

To reduce the cost of transportation, local engineers built large longboats for ore alloying along the Irtysh River to Ust-Kamenogorsk. On the Maslyanskaya adit, laid at the base of Mount Rudnaya, scientists went down to a depth of 45 fathoms (more than 95 m), examined ore in the faces, the device of drainage mechanisms, crushing and flushing devices for gold extraction.

The geologist who accompanied the expedition later wrote: “Humboldt went down the stairs to the mines, which had 90 fathoms (180 meters) deep, without fear of terrible fatigue. He turned out to be a tireless walker, all those accompanying him were exhausted. "

The next day, travelers examined the ancient, so-called Miracle workings, on which the field was discovered. Subsequently, in his book Central Asia, Humboldt, without hesitation, called the mysterious people the very same Arimaspas whom the ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote of as gold miners through the Issidons that supplied the precious metal to Greece.

After spending a little more than one day in Zyryanovsk, Humboldt went to the side of Zaysan to get acquainted with the desert area there, which seemed to him personifying the image of Central Asia. Somewhere there, just nearby was the mysterious Dzungaria.

The path passed along the Berezovka river, past the village of Myakonkaya (Solovievo), and then along the stony plateau, overgrown with feather grass and already dried up steppe grasses. Birch groves were visible along the ravines and valleys, the Cheremshansky squirrel rose to the right with a gray-green mass, far in the east, the dentate chain of the Narymsky ridge peered through a ghostly outline.

After 60 miles, travelers reached the Krasnoyarsk Cossack redoubt, located at the confluence of Narym in the Irtysh. Here they changed horses and, having moved Narym, ended up on Chinese territory. The Irtysh was all before his eyes, behind him a flat strip green lowland left bank, bordered by sandy ridges of the approaching Kalbin Highlands.

On the left, close to the road, a steep green wall of the Narymsky ridge approached, from the narrow gorges of which white-flowing rivers flowed. The rounded granite boulders sticking here and there on the foothill terrace resembled skulls of antediluvian animals.

Gradually, the valley expanded, the mountain chains, now purely stone, ridge behind the ridge went to the side, creating a surprisingly picturesque and wild landscape. The travelers stopped to admire an unusual painting reminiscent of the watercolors of Chinese artists.

“See how these hills look like frozen lava flows,” Humboldt turned to his companions. “Yes, but these are pure granites and have nothing to do with volcanoes,” Rose replied. And again, Humboldt was silently disappointed, feeling his colleague right.

His theory has not yet been confirmed anywhere. Equestrian Kirghiz came to our eyes more and more often. Local residents here were engaged not only in cattle breeding, but also in agriculture. Fields sown with millet were irrigated here with the help of artificial canals - irrigation ditches. (Irrigated in these parts of the field and in our time are used for crops).

In the town of Baty on both banks of the Irtysh there were Chinese border pickets consisting of temporary and uninhabited yurts at that time. Travelers spotted a Buddhist idol standing on the left bank, and on the island in the middle of the Irtysh huts of Russian fishermen.

By agreement with the Chinese side, Russian fishing, including military fishing, Cossack fishing, were here everywhere on the Irtysh and Zaysan. Peering into the distance, Humboldt already mentally saw Zaysan not far from here, and the immense expanses of the Asian steppes and the Tien Shan Mountains - the limit of his dreams.

Yes, he was not destined to see them! From here, the travelers turned back and returned to Krasny Yarki already at night, and on August 18 they were at Voronya pier, where two rafts prepared by the administration of the Zyryanovsky mine were waiting for them.

Each was located on three large boats, those on which the ore was smelted. A yurt was installed on the raft, in which it was possible to take refuge in case of bad weather. However, the voyage was so carried away by the travelers that they, without breaking away, watched the rocky shores pass by.

The Irtysh, sandwiched by the mountains, was narrow here, and the current was very fast. The cliffs hanging over the water itself were covered with rare pine trees and each had its own name. The shores were deserted, not a horseman flashed anywhere, not a hut, not a single haze appeared.

Peering into these wild cliffs, Humboldt recalled his travels along the rivers of South America, and Rosa barely had time to sketch the banks, paying special attention to the geological structure and bedding of rocks.

After spending the night in Ust-Kamenogorsk, travelers transferred to their bulky crews and arrived in Semipalatinsk in the late evening of August 21. Semipalatinsk, numbering a little more than three thousand people, was a semi-Russian-semi-Asian city on the border with the Kazakh steppe, which also determined the composition of its population: military, officials, merchants, raznoshintsy.

There were Russians, Tatars, and Kazakhs who lived in yurts on the outskirts of the city. The minarets of mosques and the dress of the indigenous inhabitants of the steppes gave an eastern look to the city, among which stood the Uzbek robes of Tashkent and Bukhara merchants and burqas on the heads of Muslim women.

Guests were met by the city authorities, including the mayor, he is the police chief college secretary A. Klosterman, the commandant of the fortress, Colonel K. Kempen. There was also a local entrepreneur S. Popov, whose guests were soon German scientists.

S. Popov, thanks to his wealth, vigorous activity and intellect, was a very noticeable person not only in the city, but throughout the whole region. He was known and respected not only by Russians, but also by local Kazakhs far across the steppe from the Irtysh to Tobol.

He and his people traveled a huge land in search of new deposits of gold and copper, and in this matter he succeeded so much that he began to develop most of the deposits in Central Kazakhstan in the first half of the 19th century.

More than a hundred years have passed since the activity of the Popov dynasty, but so far this surname, which has become legendary, is known to many miners and geologists now working in Kazakhstan. The Popov estate, located near Semipalatinsk, had something to see, so it is not surprising that the guests began their acquaintance with the city from it.

It was a universal economy, where various buildings were located: a capital house with services, a tannery, a mill, a sawmill, a garden with strange plants and even a domestic zoo. In the corrals of Popov’s farmyard, there were exotic black Chinese pigs, shaggy Tibetan yaks with horse tails, which the locals called wild cows, and the owner himself called Kutases.

There were argali, wild goats and even wild cats. Moreover, Popov kept this whole menagerie not only for fun and household needs, but also for sending scientists to scientific societies, with whom he kept in touch all his life.

German scientists were struck not only by zoological wonders, but also by the exemplary order and organization of the economy, and this was all the more surprising because everything happened in the wilderness, far from civilization. Russia continued to amaze enlightened Germans.

Just as in Barnaul they were amazed at Gebler's mineralogical and entomological collections and the collection of antiquities of the director of the Kolyvano-Voskresensky factories Frolov, so now they admired the garden, the home zoo and the collection of wonderful antiquities kept by their owner Popov.

The next day, Humboldt visited the guest house, where there was trade and exchange of goods imported from Russia and Europe on the one hand, and from China and India, and from Central Asian countries: Kashgar and Bukhara, on the other hand.

Most of all Germans were fascinated by Chinese objects of ancient art: porcelain and Chinese ink drawings. And much more than goods, Humboldt was interested in the stories of merchants about the distant countries of Asia, because it turned out that until the middle of the XIXth century, European scholars hardly penetrated into Kashgar; still remained the mysterious Bukhara, zealously guarding its borders. Humboldt everywhere collected interrogative information about the countries of Asia, almost at all points visited by him, statistical and other information was collected, which were later sent to Germany.

On August 22, travelers went along the highway along the Irtysh towards Omsk, where German scientists arrived on the 25th, completing a trip to Altai and the Kirghiz-Kaysak steppe.

Already on the way back, Humboldt wrote to the Prussian ambassador in Petersburg:

“We finished here our 12,000 versts from St. Petersburg ... Almost never during my hectic life I was not able to collect in a short time (6 months), however, in a vast expanse, so many observations and ideas ... The most pleasant memories were left to themselves: the space southeast of Tobolsk between Tomsk, Kolyvan and Ust-Kamenogorsk; beautiful Swiss countryside near the Zyryanovsky snow mountains of Altai"

The expedition materials were published in a number of articles, in the book Fragments on the Geology and Climatology of Asia, in the description of the trip compiled by Rosa. The completion of the publication of the trip to Altai was the capital work “Central Asia”.

One small detail characterizing A. Humboldt: of the 20 thousand rubles given to him on an expedition by the Russian government, only half of this amount was spent, the remaining 10 thousand rubles were returned to the Russian treasury.

Authority:

"Essays on the history of the Seven Rivers". Naturalist writer, photo artist, local historian Alexander Lukhtanov.