Вы здесь

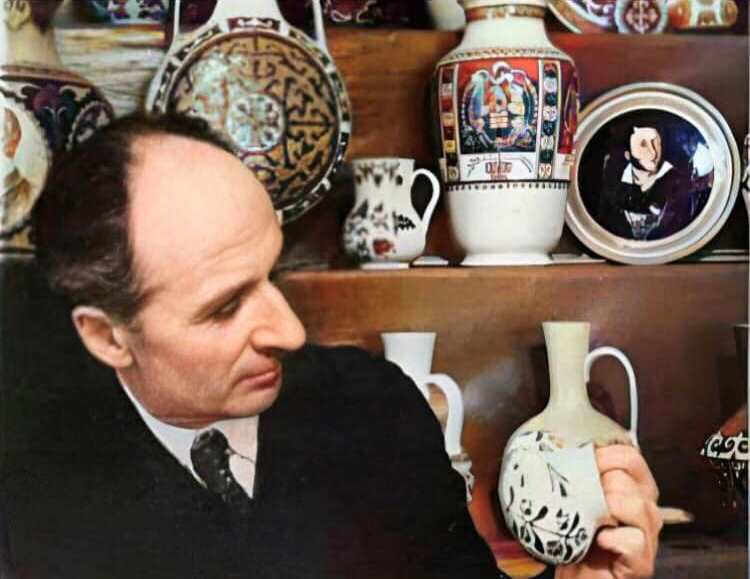

Iosif Beloskursky - first director of NEKS Alma-Ata.

Iosif Beloskursky is first organizer and director of scientific and experimental ceramic station of city of Almaty-Ata.

"Ancient craft is honorable -

a severe friendship with the foremother clay...

They take clay from brown cliffs,

and trample it, and burn it, pour it with lead,

and then outline with a wild pattern

an earthly vessel, overflowing with light, where bread will start from warm flour,

until, having blackened and cracked to the measure,

it will not put its shards into the ground,

marking by touch such and such an era."

Olga Berggolts. "About potters".

Ceramic souvenirs in Almaty.

In November 2025, it will be ninety years since the opening of the Scientific and Experimental Ceramic Station in Alma-Ata, better known as NEKS, whose highly artistic ceramic products were widely known not only in the Soviet Union, but also abroad. Currently, NEKS products, especially those made in the late 1930s - early 1940s, are highly valued by collectors not only in Kazakhstan, but also far beyond its borders.

But practically nothing is known about the history of the creation of NEKS and its first organizer and director. Even local historians studying the history of Almaty, whom I contacted, have not even heard the name of Joseph Beloskursky, a famous Ukrainian ceramist, who in 1935 organized the first ceramic production in the city of Alma-Ata (the name of the city was not declined in those years - G.A.).

The reasons for Beloskursky's appearance in Kazakhstan are still debatable: either he was forced to leave Ukraine for some reason, or he came to Kazakhstan at the invitation of the Kazak regional union of handicraft and industrial cooperation "Kazpromsoyuz", which in 1930 became a member of the All-Union Council of Industrial Cooperation (Vsekopromsovet).

About this Ukrainian master, who stood at the origins of Almaty ceramics, in the history of decorative and applied art of Kazakhstan is also offensively little known. He was called by three names - Joseph, Osip, Alexander. According to his passport, he was Joseph, in Ukraine he was called Osip, in some modern sources - Alexander.

About this mysterious man, bearing the biblical name Joseph, in 2020 I knew practically nothing. But once interest arose, I stood at the point "zero" in the middle of a huge information field. At first, I searched chaotically. There was hope that I would find all the information concerning NEKS and Iosif Beloskursky on the World Wide Web.

But it was not to be! Therefore, there was a need to go to the archives, the National Library, to find people who worked at different times in NEKS or heard about it and were willing to share their memories with me. The first information concerning his activities in Ukraine was as follows: he was born on June 17, 1883 in the city of Kolomyia (modern Ivano-Frankivsk region, Ukraine) in a poor family.

At that time, the city of Kolomyia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He studied at the Kolomyia pottery school, after graduating from which he worked at the Levinsky factory in Lviv, in 1917 he was the head of the pottery school in the city of Glinsk, a master of ceramics at the Mirgorod art and industry school named after Nikolai Gogol, founded in 1896.

Beloskursky was the author of many textbooks on ceramics:

"How to Make Clay Ware" (1911), "Ceramic Technology. For Handicraft and Industrial Schools and Training Workshops" (1928), "Clay Lid and How to Make It by Hand and Machine" (1930), "Ceramic Technology Course" (1930), "Kaflarstvo" (1932). foreign specialists began to be attracted to teaching at the school: the German Emil Maute, Austrian citizens Stanislav Patkovsky, Ignatiy Berezovsky, Franz Pech, Iosif Beloskursky" [1].

If in some Ukrainian sources there are documented facts about the activities of I.N. Beloskursky in Ukraine [2], and even then with some inaccuracies and errors, then little is known about the Kazakhstan period of his life and his activities as the first director of NEKS.

Information about him is extremely scanty, fragmentary, sometimes, with the "light" hand of some researchers, erroneous. On one of the antique forums I found some information about Beloskursky with a link to the dissertation of the Kazakh art historian Svetlana Vitalievna Shklyaeva on the topic "Problems of the development of applied art in Kazakhstan: the Soviet era - the period of independence" for the degree of candidate of art history, which she defended in 2010.

In the library of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan I found her dissertation, which, in my opinion, contains a number of annoying inaccuracies. Thus, even one of the letters of Beloskursky's initials is incorrect. S.V. Shklyaeva wrote:

"In 1935, the Scientific and Experimental Ceramic Station of the Kazpromsovet was organized in Alma-Ata. The station was headed by A.N. Beloskursky, an invited specialist from Western Ukraine. According to the memoirs of F.A. Pisman [3], recorded by me in 2004, A.N. Beloskursky taught at the Lviv Polytechnic Institute, doing research: his textbooks and research on ceramics were well known in Ukraine" [4].

According to S.V. Shklyaeva, with whom a telephone conversation took place on February 13, 2023, Beloskursky was called Alexander Nikolaevich by the former chief artist of the art ceramics plant Felix Andreevich Pisman. It can be assumed that he confused the name of the first director of NEKS, since he began working at the ceramics station only on November 11, 1968 [5], that is, twenty-five years after Beloskursky's death. Excerpts from S.V. Shklyaeva's dissertation ended up on the World Wide Web, thus cementing the erroneous spelling of the name of the first organizer and director of NEKS: "A.N. Beloskursky".

Unfortunately, this error became a cascade, repeating itself in subsequent articles by S.V. Shklyaeva [6, 7] and migrating to the studies of authors from other countries [8]. Even now, eighty-one years after the death of Joseph Nikolaevich Beloskursky, it is striking in the texts describing NEKS ceramic products on Kazakhstani and foreign marketplaces.

In the book by the Kazakhstani architect T.K. Basenov “Applied Art of Kazakhstan”, there is not a word about Beloskursky, although there is a mention of the ceramic station he created in the city of Alma-Ata:

“Industrial artels have a narrowly specialized profile and choose decorative and applied art as their main direction in creativity. Such are, for example, the Scientific and Experimental Ceramic Station of the Kazpromsovet in Alma-Ata, the “Kovrovshchitsa” artel and others” [9].

In the book by G. Pozdnyakova and N. Sinenkaya “Kazakh Souvenirs”, there is also no mention of the organizer and first director of NEKS. It is only written that “the main center for the creation of modern ceramics in Kazakhstan is the Alma-Ata Experimental Plant of Artistic Ceramics. It grew out of a scientific and experimental station founded in 1935” [10].

As a result, I had to go to the archives: the Central State Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the archive of the Kazakh National Medical University named after S. Asfendiyarov and the State Archive of the city of Almaty. Why did I first go to the archive of the Kazakh National Medical University named after S. Asfendiyarov?

I was lucky to find, meet and meet several times with Valentina Fedorovna Sadovskaya, born in 1940, who worked her entire life at the plant of art ceramics (former NEKS) from a student to the chief artist. Once she let it slip that Beloskursky’s wife, the technical director of the station Antonina Timofeevna Nikitina, advised her daughter to study to become a doctor.

Sadovskaya came to the station in 1958, right after finishing school, and studied drawing with Nikitina for three years until she retired in 1961. If the daughter had listened to her mother's advice, she should have entered the only medical institute in Alma-Ata. My guesses were correct.

Galina, having graduated from school No. 36 named after L.M. Kaganovich with a silver medal in 1951, entered the Alma-Ata Medical Institute named after V.M. Molotov. A list of graduates of the medical faculty of 1957 was found, in which Galina Iosifovna Beloskurskaya was listed under number thirteen.

The article "A New Look at Ceramics" from the magazine "Antique" No. 93 (November-December 2015) says that "from the moment of its foundation until the 1930s, In the MHPS (Mirgorod Art and Industrial School – G.A.), the artist and ethnographer Opanas Slastion, the architect and graphic artist Vasily Krichevsky, the artists Efim Mikhailov, Ivan Padalka, Fotiy Krasitsky, the sculptors Evgeny Sagaidachny, Fyodor Balavensky, the graphic artist Sofia Nalepinskaya-Boychuk, the ceramist Iosif Beloskursky taught and worked creatively”, “with the growing popularity of Mirgorod art products within the Russian Empire and at international exhibitions, Fortunately, after a long search in the archives of the KazNMU, even the personal file of G.I. Beloskurskaya, born in 1933, a Ukrainian, was found.

In one of her two autobiographies, personally written by hand, there is confirmation that her father, Beloskursky Iosif Nikolaevich, a Ukrainian by nationality, a non-party member, died of a serious illness on August 26, 1943 [11]. Working with documents from the Almaty city archive, I found a death certificate for Iosif Nikolaevich Beloskursky, who died of pneumonia in the city of Alma-Ata, Vinogradov Street, 121, in civil death records from No. 1001 to No. 1473 of the Stalinsky District of the city of Alma-Ata under No. 1450, dated August 26, 1943 (medical death certificate of the Turksib Polyclinic). Passport III PH No. 530762. Applicant - Startseva [12]. The Beloskursky family lived in house No. 121 on Vinogradov Street, near the station.

The reasons for Beloskursky and his family's appearance in Alma-Ata have not yet been documented. Oles Poshivaylo, a well-known Ukrainian researcher and ceramologist, cites a quote from ceramologist Alexander Tishchenko that "after the Makaro-Yarovskaya ceramic handicraft and industrial school was closed in 1935, its master Mikhail Kiryachok, along with a group of masters, left for Kyrgyzstan, where the Ukrainian ceramic technologist Osip Beloskursky allegedly organized pottery production."

But then he adds that "one of the school's students, Adam Voskoboy, testified in one of his letters that Mikhail Kiryachok left not for Kyrgyzstan, but for Kazakhstan." He also reports the following: “Moreover, until now no scientist has said so clearly that artists and technologists rushed to Central Asia not of their own free will and not at all because there was no suitable work for them in Ukraine.

In fact, talented people saved themselves and their families from Beria’s repressions in this way: in Ukraine, they had only one prospect - to end their earthly journey in the dungeons or camps of the NKVD. Perhaps they left there by force, as if in exile, by the court of the repressive organs” [13].

Unfortunately, the article does not provide evidence for such an assumption regarding Joseph Beloskursky. I do not have archival documents proving the fact of Beloskursky’s persecution by the NKVD and his forced departure from Ukraine. The most probable version of Beloskursky's appearance in Alma-Ata, in my opinion, may be the fact that in the early 1930s Ukraine took patronage over Kazakhstan, where "the construction of the Cossack proletarian culture is unfolding, a culture national in form, socialist in content.

Universal education, polytechnicization, and the elimination of illiteracy are unfolding." Thus, on July 5, 1931, a special correspondent from Kharkov named Gorb reported that a train with polytechnic equipment "will be sent in the first half of July. It will include equipment for four technical stations, twenty-nine workshops, twenty-six workrooms, various kinds of auxiliary materials, libraries.

The train will be accompanied by shock workers, Komsomol members, schoolchildren, pioneers and representatives of Soviet Ukraine. The sending of a train of polytechnic equipment by Ukraine to Kazakhstan, undoubtedly, has profound political significance; this is an extremely striking fact in strengthening the international, fraternal ties of the two Soviet republics" [14].

It is quite possible that it was within the framework of such international, fraternal assistance that the Ukopromsovet could, at the request of the leadership of the Kazpromsovet under the Council of People's Commissars of the Kazakh SSR, send Ukrainian specialists, including ceramicists, to Alma-Ata to organize the activities of an experimental ceramic station.

Moreover, Beloskursky worked in the Ukopromsovet in 1932, organized the work of several ceramic stations (for example, in Bakhchisarai and Kharkov), demonstrating his undoubted organizational skills and professional competencies. It can also be assumed that the Kazpromsovet offered him a competitive salary, payment of a transfer fee and free housing.

This assumption is supported by some documents of the NEKS from the Central State Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the State Archive of the city of Almaty. It is this version that seems very plausible to me. It also seems possible that he came to Alma-Ata not only with his wife and little daughter, but also with several students.

This assumption of mine, as I studied the archival documents, was partially confirmed by the retrospective documents of the NEKS. For example, in the folder “Historical information about the scientific and experimental factory for 1968” it is written that "the talented artist and teacher comrade Beloskursky taught his craft to many students from among the youth, both local and invited from Ukraine" [15].

It should be noted that NEKS did not arise out of thin air. In the city of Verny (former name of Almaty), many residents were engaged in crafts, including pottery, as evidenced by the names of their places of residence: Kuznechnye ryady, Kirpichnaya street, Torgovaya street, two Sadovye streets and two Goncharnye streets.

In the list of members of the Verny Union of Urban Cooperatives of 1919, I counted 352 people, of whom 15 lived on Goncharnaya street [16], which gives me some reason to assume that they were engaged in pottery. It must be admitted that in the city of Verny from the very beginning there was confusion with the names of streets, at least this concerned the second- and third-rate ones, that is, the outskirts. Later, this tradition remained in Alma-Ata, which became the capital of the young union republic.

Two Furmanov Streets, two Michurin Streets, two Proletarskaya Streets, two Goncharnaya Streets, two Sadovaya Streets, two Komsomolskaya Streets, and even three streets named Ovrazhnaya Street. In the directory “Alma-Ata Streets”, prepared by the Bureau of Technical Inventory on the instructions of the Executive Committee of the Alma-Ata City Council of People’s Deputies with the stamp “For official use only” and published in 1982, under number 230 is indicated “2-ya Goncharnaya Street, north of 50th Anniversary of October Avenue, east of Aerodromnaya Street, Leninsky District” with the note “Pottery production was previously widely developed in this area of the city” [17].

This street still exists in the Zhetysu District of Almaty. Under number 716 in this directory is the street "Muratbaeva (former Goncharnaya), south of 50-letiya Oktyabrya, between the streets. Kozhamkulova and Shagabutdinova, Leninsky (from 1 - 97, from 2 - 62) and Sovetsky (from 92 and 99 to the end) districts, with the note "Muratbaev Gani (1902 - 1925) - the organizer and leader of the first Komsomol organizations of Kazakhstan and Central Asia" [18].

Here is what A. G. Lukhtanov wrote about Goncharnaya street:

"By the beginning of the 20th century, the penultimate western street (on Kuchugury), stretching from the prison in the north to the Main aryk in the south for 2700 m. The name is associated with the artisan potters, Dungan and Uyghur settlers living in the northern part of the street. It was built up with one-story houses of two types: adobe and wooden, often with reed roofs, which survived until the 50s of the 20th century" [19].

In the early thirties, along the Malaya Vesnovka River (now the Esentai River) on Goncharnaya Street, the first houses of individual developers appeared, which were built without any plans, so from an architectural point of view, this area was an unorganized spontaneous settlement. Potters dug clay right here, by the river, and when necessary, they brought it from Remizov Gorge.

At the intersection of Goncharnaya and Vinogradov Streets, there was a small pottery workshop, which belonged to an owner of Tatar nationality. His last name, according to V. F. Sadovskaya, was Khaliullin, but she did not remember his first name.

Although in the "Reference on the activities of the Ceramic Station for 1951 - 1958" dated January 10, 1959 it is noted:

"For 23 years of its existence, the production of the Ceramic Station continues to operate in the premises of the former owner, the potter Bikbulin, on Vinogradov and Goncharnaya Streets" [20].

I did not find an order of the Kazpromsovet on the appointment of I.N. Beloskursky as director of the Ceramic Station in the archives. Unfortunately, few retrospective documents from that period have survived. But in the decrees of the Presidium of the Kazpromsovet preserved in the Central State Archives of the Republic of Kazakhstan, several documents were found confirming the activities of Beloskursky in 1936 - 1937. For example, one of the resolutions of April 17, 1937 stated that “The plan for the 1st quarter (1937 – G.A.) for the Keramstantsionnaya was not fulfilled for all indicators... the scientific and experimental work envisaged by the plan was not sufficiently developed.

This volume of work is explained by the absence of Comrade Beloskursky for a month, who was on a business trip to Ukraine, as well as his illness” [21]. The resolution of June 4, 1937 stated: “The report of the director of the NEKS – Beloskursky from 15-V-37 on a business trip to the city of Kharkov s/kommand. certificate No. 8311 from 31 – 1-37 – submitted in the amount of rubles. 1630-39 to be approved in the amount of rubles. 1560-04.

Indicate comrade. Beloskursky on the inadmissibility of submitting a report without a mark on the arrival and departure of local organizations on the command. certificate." [22]. Why did Iosif Nikolaevich go to Kharkov? It can be assumed that there were several reasons for his business trip, and one of them was the invitation of Ukrainian ceramic masters to go to work in Kazakhstan.

The very first mention of NEKS appeared in the city newspaper in November 1935: “The Kazpromsovet organized an experimental ceramic station for the production of artistic tableware in Alma-Ata” [23]. In 1938, it was reported that “at the end of 1935, on Vinogradov Street near Malaya Vesnovka, the Kazpromsovet opened a scientific and experimental ceramic station” [24].

On June 19, 1945, a service note was received in the name of the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Kazakh SSR, Comrade Undasynov, entitled “On the scientific and experimental ceramic station of the city of Alma-Ata”, signed by the authorized representative of the USSR People's Commissariat of Foreign Trade for the Kazakh SSR Bogdasarov. In it he writes:

“At the end of 1935, a small ceramic workshop was organized in the city of Alma-Ata, which was part of the Kazpromsovet system, the first director of which was the now deceased ceramic artist Iosif Nikolaevich Beloskursky, who invested a lot of effort, energy and labor in the creation of artistic ceramics in the conditions of meager funds that were allocated by the Kazpromsovet for the work of this workshop, an unsuitable small room, a lack of qualified personnel, etc.” [25].

The biography of Iosif Beloskursky was described by his wife, Antonina Timofeevna Nikitina, who worked as a technical director at NEKS from 1936 to 1961, in a letter to the Ukrainian ceramologist Yuri Lashchuk, which he received in 1971. In it, in chronological order, the stages of her husband's biography were listed in detail (where, when and by whom she worked).

As for the Beloskursky family's appearance in Alma-Ata, Nikitina explained this fact by the fact that "in the fall of 1935 he was invited (highlighted by me - G.A.) to Kazakhstan, to the city of Alma-Ata, to organize a Scientific and Experimental Ceramic Station similar to the station organized in the city of Kharkov" [26].

The version of the father's invitation to Alma-Ata is twice confirmed by his daughter Galina. In her second autobiography, when she was already a sixth-year student (1956 - 1957), she writes that she was born "on February 16, 1933, in the family of an employee in the village of Pesochin, Kharkov region, Ukrainian by nationality.

She lived in Kharkov until she was 2.5 years old, then in 1935 she moved to Alma-Ata, where her father was sent (highlighted by me - G.A.) as the director of the Scientific and Experimental Ceramic Station" [27]. In her first autobiography, written upon entering the Alma-Ata Medical Institute named after V.M. Molotov in 1951, she describes her father's activities in Ukraine in sufficient detail:

"My father, Iosif Nikolaevich Beloskursky, a ceramic engineer by profession, was the head and teacher of a ceramics school in Ukraine before the revolution. After the revolution, he worked as a senior inspector and methodologist-referent of the scientific sector of the People's Commissariat of Education of Ukraine.

Then he worked as a director in the scientific ceramic station of clay and ceramics of the Vukopromsovet, which he organized. In 1935, he was appointed (highlighted by me - G.A.) organizer and director of the scientific experimental station in the city of Alma-Ata, where he worked in this position for 8 years.

He died in 1943. Non-party member. My mother, Antonina Timofeevna Nikitina, worked in Kharkov as a ceramic artist until 1935. From 1935 to the present day, she has been working at the Scientific Experimental Ceramic Station as a technical director. Non-Party" [28].

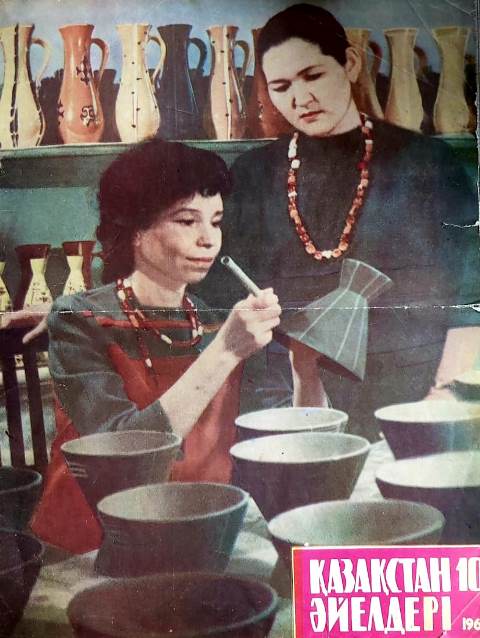

In 1936, a photograph of a two-handled "Etruscan vase" [29] made at the Ceramic Station (I assume by I.N. Beloskursky) appeared in the newspaper "Socialist Alma-Ata". In the following years (1937-1938), photographs of master sharpeners and draftswomen of the Ceramic Station (as NEKS was then called) were published, painting vases from local pottery clay. In the article “Alma-Ata Ceramics” K. Saprykin writes:

“In June, highly artistic clay dishes will appear on the shelves of Alma-Ata stores: large decorative vases with Kazakh ornaments, artistically decorated sugar bowls, butter dishes, flower bottles, dishes, etc. covered with shiny glaze. These products are being prepared for the first time by the Ceramics Department of the Alma-Ata Scientific Experimental Station of the Kazpromsovet (Vinogradova, 115).

The experiments of the director, researcher Comrade Beloskursky, on the use of local clay materials, the search for paints and the adaptation of glaze to local clay for the production of artistic products turned out to be very successful. Based on these experiments, Comrade Beloskursky has grown a small ceramic workshop with great prospects.

A shapeless piece of elastic clay from the Remizov Gorge, rotating on a wooden machine, in the hands of a specialist sharpener, in a few minutes turns into a vessel. The vessel is dried, processed again on the machine, then it passes into the hands of other craftsmen, who cover it with glaze, draw an ornament on it with cutters.

The drawings are made with multi-colored porcelain clay, tinted with metal oxides, and the vessel is fired in a kiln. Once again the vessel is glazed, fired and finally it is ready for sale. This is how the production of these wonderful things is organized, of which 5 thousand rubles have already been produced.

18 samples of the station's products were sent to Moscow for the Kazakh Art Decade, some are transferred to the Alma-Ata Museum, the rest are purchased by KazTorg for sale in the city. Every month the ceramic station will prepare products for 10,000 rubles.

Now the station is taking on the production of decorations for the facades of houses and tiles with Kazakh ornaments. There are only 15 workers at the station. The station needs personnel - skilled Kazakh ceramicists. A great project has been started, it needs every possible help" [30].

Beloskursky became widely known, first of all, because at the World Exhibition "Art and Technology in Modern Life", held in Paris from May 25 to November 25, 1937, NEKS ceramic products received a silver medal and a diploma. S.V. Shklyaeva mentioned in a telephone conversation that Beloskursky was awarded a silver medal for a ceramic vase with a portrait of A.S. Pushkin based on the painting by I.N. Kramskoy.

But the famous Kazakhstani journalist Anatoly Ivanov-Vaiskopf, who worked at the art ceramics plant in the early 1980s, recalled during a personal meeting on October 16, 2023, that "the exposition of the plant's museum contained almost all the works of the plant's artists, starting from the 1930s of the last century.

The most valuable work was considered to be a small ceramic plate with a diameter of twenty-five centimeters, on which a portrait of A.S. Pushkin was depicted. In 1937, it received a silver medal at the World Exhibition in Paris, as evidenced by the corresponding certificate."

It is not entirely clear whether it was a vase or a plate with a portrait of Pushkin, but it was the first international success of Kazakh ceramics since the proclamation of the young republic. "Of the 30 million spectators who visited the exhibition in June-November 1937, about 20 million visited the USSR pavilion - the largest number among the pavilions of 44 countries.

The pavilion collected 265 awards, of which there were 95 grand prix, 70 gold medals, 40 silver, 6 bronze and more than fifty diplomas" [31]. This was an absolute country record at the World Exhibition in Paris. 1936 was a significant year for the entire country - from November 25 to December 5, the VIII All-Union Congress of Soviets was held, at which a new, "Stalinist" Constitution was adopted.

And the Kazakh Republic prepared for the congress very seriously. Among the many gifts, gifts made by workers of the Kazpromsovet artels stood out. Alma-Ata ceramics took pride of place among them – the Keramstantion presented beautifully made dishes with images of Lenin, Stalin and members of the Politburo.

The newspaper “Socialist Alma-Ata” published an article by NEKS artist Yakup Ibragimov “When you draw the face of the leader...”: “there are not even enough words to express my gratitude to the creator of the Constitution, my own father, Comrade Stalin.

All these days, when the congress was taking place and the Constitution was being approved, I was drawing Comrade Stalin in Kazakh ornamentation. And when you draw the beloved face of the leader, then your heart becomes somehow joyful and you want to draw better and better” [32].

It was from these gifts that the Moscow commission selected exhibits presented by the Union republics for the Paris exhibition in 1937. The authorized representative of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Trade of the USSR for the Kazakh SSR, Bogdasarov, wrote in the above-mentioned memo in 1945:

“In 1937, 13 exhibits were exhibited at the World Exhibition in Paris, where, judging by the reviews in the press, they also attracted everyone's attention for their masterful execution, original form and coloring. From Paris, Kazakh ceramics were sent to the exhibition in Liverpool (England), and it should be noted that the jury of the Paris exhibition awarded I.N. Beloskursky a large silver medal for his products.

Some of the exhibits prepared for the Paris exhibition were transferred to Moscow museums” [33]. Later, Kazakh newspapers wrote about this: “Recently, the scientific and experimental ceramic station of the Kazpromsovet sent several vases and dishes with a portrait of the Kazakh folk singer Dzhambul to the Vsekompromsovet in Moscow.

These items are scheduled for delivery to the Paris exhibition. Now the artist Ibragimov is preparing new exhibits for the Paris exhibition. Among the exhibits is the People's Artist of the USSR Kulyash Baiseitova in the role of Kyz-zhibek, performed in a Kazakh ornament on a dish” [34],

“In two and a half years, the ceramic station has become popular with its high-quality products not only in the Soviet Union, but also beyond its borders. The vases were presented at an international exhibition in Paris and received a good rating” [35].

A museum was even set up in the station’s premises: “The station’s management organized a ceramics museum in one of the station’s rooms. This museum exhibits samples of all the products produced by the station. During the first days, the museum was visited by over 100 students and schoolchildren of the city” [36].

The NEKS itself is organizing courses to train sharpeners, "The ceramic station will train ceramic masters for Kustanai and Chimkent, where the Kazpromsovet organized ceramic production in 1939" [37]. In connection with this, advertisements from the Ceramic Station appeared in newspapers inviting everyone with an aptitude for drawing and ceramicists of Kazakh nationality to work.

Beloskursky managed the ceramic station for eight years. After his death, his wife, technical director Antonina Timofeevna Nikitina, worked there for eighteen years (until her retirement). She survived five directors and actually managed it, steadfastly and carefully preserving her husband's traditions of producing artistic ceramics of the highest quality.

"She was the successor to Beloskursky's work... she managed the station's production continuously from 1943 to 1961, and taught her craft to many drawing students" [38]. The place where Beloskursky was buried is still unknown. In 1943, many soldiers and officers were buried in the city; they were brought wounded by evacuation trains from the west of the country to the hospitals of Alma-Ata.

Many of the wounded were treated, but many died from their wounds. “In 1938, the city of Alma-Ata had only five cemeteries (located, according to documents, “near the city”), of which four were located: near the Tashkent highway (Central), between Tatarskaya and Novaya Slobodka (liquidated in the 1950s), north of Malo-Alma-Atinskaya stanitsa (now a closed cemetery on Kabilova Street in the Medeu district) and south of the city, behind the brick factory (liquidated), and one near the village of “Pyatiletka”, on the left bank of the Sultan-Karasu stream (now the Northern cemetery in the Turksib district)” [39].

Unfortunately, it is currently impossible to find the grave of Joseph Nikolaevich Beloskursky. It is necessary to continue further searches in state archives and funeral service organizations of the city of Almaty. The NEKS vases of the period when Beloskursky worked (late 1930s - early 1940s), stored in the State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Kazakhstan named after A. Kasteyev, the Museum of Almaty, the library of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the museum of the Kazakh National Medical University named after S. Asfendiyarov and in private collections, still amaze with their heavenly beauty.

Authority:

Akhmetova Gradislava Robertovna, PhD in Economics, MA, MBA, General Director of Governance & Management Consulting.

No. 2 (35) 2024. Bulletin of the archival service of the city of Almaty. Information and methodological publication (frequency of publication 2 times a year).

Literature and authority:

- https://lnam.edu.ua/files/Academy/event_images/rizne%202021/KOD_1_5_vse-1.pdf (date of access October 19, 2024).

2. The ceramic code of Ivan Levinsky in the aesthetic world of Ukrainians of the XIX-early XX centuries. - Kharkiv: Rarities of Ukraine, 2020. - P. 72 - 73.https://lnam.edu.ua/files/Academy/event_images/rizne%202021/ KOD_1_5_vse-1.pdf (date of access - November 21, 2024).

3. In the dissertation of S.V. Shklyaeva writes the surname of the former chief artist of the Alma-Ata plant of artistic ceramics "Pisman", although in my conversations with former employees of the plant they insisted that the correct spelling of the surname of Felix Andreevich is Pisman. In the orders and other documents of the NEKS, stored in the State Archives of the city of Almaty, it is written "Pisman". That is why I write "Pisman".

4. Shklyaeva S.V. Problems of development of applied art of Kazakhstan: Soviet era - period of independence. Dissertation for the degree of candidate of art history. - Almaty, 2010. - P. 14.

5. In the order of the Ceramic Station No. 269 dated November 12, 1968 it is written: "Pisman Felix Andreevich to be hired as a model maker in the 6th category from November 11, 1968 with a salary of 104 rubles. per month and 40% bonus upon completion of the task. Accepted by transfer in accordance with the agreement of the managers." - State Archives of the City of Almaty. F. 218. Op. 2. D. 175. L. 338.

6. Shklyaeva S. Some aspects of the activities of artels in Kazakhstan during the Great Patriotic War // Proceedings of the international scientific conference dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the victory in the Great Patriotic War "War, trouble, dream and youth! Art and war." – M. BuksMArt, 2015. - P. 169.

7. Shklyaeva S.V. Traditions in the development of applied art in Kazakhstan: the Soviet era - the period independence // Contemporary art of the East. Collection of materials of the international scientific conference. – M.: Moscow Museum of Modern Art, State Institute of Art Studies, 2017. – P. 176. https://www.hse.ru/data/2017/12/15/1075865059/%D0%A1%D0%98%D0%92-2015.pdf (date of access – November 21, 2024).

8. Golsky I.A. Collection of ceramics and porcelain of Kazakhstan in the Omsk Museum of Fine Arts named after M.A. Vrubel. Catalog // Collection of scientific works of the Omsk Museum of Fine Arts named after M.A. Vrubel. – Omsk, 2016 – P. 125. https://vrubel.ru/downloads/SbornikNauchnihTrudov.pdf.

9. Basenov TK Applied Art of Kazakhstan. - Alma-Ata: Kazakh State Publishing House of Fiction, 1958. - Page 14.

10. Pozdnyakova G., Sinenkaya N. Kazakh Souvenirs. Alma-Ata: Kazakhstan Publishing House, 1976. - Page 91.

11. Archive of the Kazakh National Medical University named after S. Asfendiyarov. - F. 29. Op. 2. D. 15032. L. 2.

12. State Archive of Almaty. F. 287. Op. 1-pr. D. 675. L. 59.

13. Oles Poshivaylo. About the disadvantage of permanent information nomadism in Ukrainian ceramic biographies (technology and inheritance of ceramic plagiarism) // Collection of Ukrainian ceramics. Opishne, 2019 – P. 269. https://knigozbirnia.opishne-museum.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/pe...(accessed October 28, 2024).

14. Soviet steppe. – 1931 – July 5. – No. 147.

15. State archive of the mountains. Almaty. F. 218. Op. 2. D. 179. L. 4.

16. State archive of the mountains. Almaty. F. 292. Op. 1. D. 7. L. 5-10.

17. Streets of Almaty. – Alma-Ata, 1982 – P. 29.

18. Streets of Almaty. – Alma-Ata, 1982 – P. 81.

19. Lukhtanov A.G. The city of Verny and Semirechensk region. The illustrated encyclopedia, third edition. – Almaty, 2014 – P. 82.

20. State archive of the mountains. Almaty. F. 218. Op. 2. D. 58. L. 4.

21. Central State Administration of the Republic of Kazakhstan. F. 1743. Op. 1. D. 231. L. 103-104.

22. CSA RK. F. 1743. Op. 1. D. 231. L. 196.

23. Socialist Alma-Ata. – 1935 – November 17.

24. Socialist Alma-Ata. – 1938 – March 2.

25. CSA RK. – F. 1743. – Op. 2. – D. 690. – L. 21.

26. Oles Poshivaylo. About the disadvantage of permanent information nomadism in Ukrainian ceramic biographies (technology and inheritance of ceramic plagiarism) // Collection of Ukrainian ceramics. Opishne, 2019. – P. 271. https://knigozbirnia.opishne-museum.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/personalii.pdf (accessed October 28, 2024).

27. Archive of the Kazakh National Medical University named after.

S. Asfendiyarova. – F. 29. Op. 2. D. 15032. L. 8.

28. Archive of the Kazakh National Medical University named after. S. Asfendiyarova. – F.

29. Op. 2. D. 15032. L. 2. 29. Socialist Alma-Ata. – 1936 – June 2.

30. Socialist Alma-Ata. – 1936 – May 16.

31. RGASPI (Russian State Archive of Social and Political History). F. 82. D. 762. L. 94, L. 82-87. Cit. by E. Konysheva. “Superiority Complex”: the USSR Pavilion at the World Exhibition in Paris and Soviet Cultural Diplomacy // Quaestio Rossica. – 2018.– Vol. 6. – No. 1. – P. 178. https://elar.urfu.ru/bitstream/10995/59921/1/qr_1_2018_13.pdf (date of access - October 30, 2024).

32. Socialist Alma-Ata. - 1936. - December 8.

33. TsGA RK. F. 1743. Op. 2. D. 690. L. 21.

34. Socialist Alma-Ata. - 1936. - October 21.

35. Socialist Alma-Ata. - 1938 - March 2.

36. Socialist Alma-Ata. - 1938. - June 4.

37. Socialist Alma-Ata. - 1938 - December 16.

38. State Archives of Almaty. F. 218. Op. 2. D. 179. L. 1.

39. Afonin G.A. Central Cemetery of Almaty as a Historical and Memorial Necropolis. Materials on the History of Foundation, Reconstruction and Chronology. Almaty State Archive of Historical and Memorial Necropolises. – 2018. – No. 1. – P. 100.