You are here

Artefacts Margush in museum Arts.

Tours on ancient settlement Gonur depe - Margush.

"A variety of articles of gold, silver, bronze, stone, ivory, ceramics and green clay impress not only with their quality but also with perfect execution. They open up the veil of secrecy over the most unexplored periods of history of the Bronze Age and recreate the characteristics of the society that used to trade with other major urban communities in the Near and Middle East, as well as with the Indus civilization"

Pilgrimage tours on Ashgabad.

After two years of painstaking restoration work, the antiquities hall of the Ashgabat Museum of Fine Arts opened a permanent exhibition of rare articles from the excavations of the Margiana Archaeological Expedition that for many years was headed by the famous scientist, honorary member of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor Victor Sarianidi.

The funds of this museum and two other major museums of Turkmenistan received a myriad of finds excavated by his legendary expedition, including extremely unique things that no other museum in the world is likely to have.

A variety of articles of gold, silver, bronze, stone, ivory, ceramics and green clay impress not only with their quality but also with perfect execution. They open up the veil of secrecy over the most unexplored periods of history of the Bronze Age and recreate the characteristics of the society that used to trade with other major urban communities in the Near and Middle East, as well as with the Indus civilization.

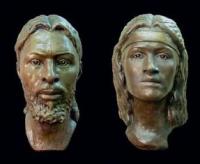

Finally, they allowed researchers to look into the spiritual world of people who lived at the turn of the third and second millennium BC. Stone mosaics from the "royal" burials of Gonur Depe - the central settlement of ancient Margiana - are the main theme and intrigue of the new museum exposition, that was devised and implemented by designer Allanazar Sopiev. They were discovered back in 2004.

Following primary conservation, they remained sealed for quite long in the storage facility until the directorate came up with a project for their restoration by applying for a grant of the US State Department's Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation.

The initiative was approved. In 2014, hard and long work began at the museum's restoration laboratory. Foreign experts were invited for this purpose. They included employees of the State Research Institute of Restoration (Moscow) of the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Natalia Kovaleva and Galina Veresotskaya, as well as restorer Tatyana Shaposhnikova from the State Museum of the History of Religion (St. Petersburg).

Jointly with their Turkmen counterparts Mekan Annanurov and Annamurad Orazov they restored three large fragments from the massive chest-tabernacle and several decorative panels from the walls of the royal tombs. They managed to recreate relatively complete pictures out of thousands of different "puzzles".

At first glance, these pictures depict unusual scenes from an unimaginably distant past. Here are the two winged lions with bared jaws looking at each other in aggressive poses, and between them are the creatures in long robes with outstretched wings.

There are also huge snakes swallowing argali, and there is a stand-alone griffin on a cartouche. There are many scattered fragments in the form of heads and torsos of predators, birds, fish, as well as a scattering of human eyes and only one whole image of a woman's face. These are all the most important, most effective details of stone mosaics.

One of the expedition participants, geologist Alexei Yuminov from the Institute of Mineralogy of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, found out that stones from which the mosaic insets were cut were preliminarily subjected to strong heating that destructed the original structure of the mineral.

The material would become softer and usable for artistic carving. There were also found tools used by the Gonur masters. These are stone chisels sharpened at such an angle that made it possible to cut out the mosaic details exactly of the same shape as those found at Gonur.

It became clear that all these works were made locally, they were not brought from somewhere. Raw materials were also local, minerals were mined in Kopetdag mountains. Scientists have learned a lot about the technology of manufacturing of these mosaics.

They noted several types of symbols on the back of some inserts marking the mosaic details. By all appearances, a hard wooden frame covered with sand-lime mortar was used as the basis for creating each mosaic panel.

Then, an adhesive layer was applied to this surface, fixing the mosaic set. The space between the stone inserts was filled with dyes - black, blue and bright red. In other words, all Gonur mosaics are the works of the mixed mosaic-picturesque technique.

Another group of the preserved mosaics is ornamental. One can see several types of geometric shapes, some of which resemble carpet patterns. They consist of triangular, square and rectangular-linear elements.

There are even unusual ornaments with a figure resembling a card suit of hearts or the leaves of pipala - a sacred fig tree growing in India - serving as the base element. It was this design that adorned the so-called tabernacle, a treasure chest found in one of the Gonur mausoleums, which is now displayed at the Ashgabat museum in the reconstructed form.

However, thematic mosaics still remain the most intriguing and mysterious.

They take us to the almost forgotten world of ancient Eastern myths, in which the images of animals served as an allegory of cosmological ideas of people of that time. Animalistic scenes played an important role in the art of the first civilizations that existed in the region of the so-called Fertile Crescent from Egypt to Iran beginning the fourth millennium BC.

At first, the images were quite naturalistic until the Bronze Age, when heraldic compositions began to appear. A group of three figures, including either a man, or a tree, or an animal surrounded by the images of heraldic animals was the most popular among the new motifs.

Originally, the central figure represented the Mesopotamian God Gilgamesh, while the beasts embodied the power of permanently hostile Darkness. Later, it was replaced by the Great Goddess, and the animals were understood to be her servants. At the same time, hunting scenes appeared in the art.

The images of mysterious animals spread from the third millennium BC. In the second millennium, aggressive lions with ferocious muzzles were a common motive in the art of the Hittite Empire and, as it turned out, in ancient Margiana.

The winged lions marked the important role of power from both the political and religious points of view. According to researchers of the ancient Eastern mythology, griffins with the heads of lions and eagles were the guards of the other world and keepers of jewelry that were left in the underground crypts as funeral offerings.

Initially, there were seals and amulets, and now there are the stone mosaics from Gonur that confirm that there existed an original animalistic style in art. The mosaics with the scenes of tearing of cloven-hoofed mammals by snakes or dragons are quite visible prototypes of the most popular plot in the East that depicts a lion attacking a bull.

For many centuries, it had served as a symbol of spring equinox. A lion was believed to personify the sun and power, and a bull symbolized land and wealth. A lion that kills a bull is an allegory of the astronomical phenomenon and the oldest agricultural festival of Novruz.

On March 21, spring asserts its rights, the constellation of Leo is at its zenith, and the Taurus disappears from the horizon. The scenes of tearing and struggle of animals can be surely interpreted more broadly, as symbols of unity and struggle of opposites (yin/yang, day/night, life/death, summer/winter).

However, their emergence in the Bronze Age in southern Central Asia and northern Iran is clearly connected with the emergence of the agricultural calendar. A few more centuries passed before the birth of the world-famous unique phenomenon of the world art - the Scythian-Siberian animal style that was widespread among the peoples of the Great Belt of the Steppes from the Danube in Eastern Europe to Ordos in Northern China.

However, the origins of this style, as evidenced by the mosaics from Gonur Depe, were in the south, in the fertile valley of Murgab River that was part of the cultural zone of the so-called Oks civilization, namely of the Bactrian-Margian archaeological complex whose discovery deservedly belongs to Professor Sarianidi.

Authority:

Ruslan Muradov. 2017 N7-8(148 - 149) http://www.turkmenistaninfo.ru

Photos in the lower part of the page

Alexnder Petrov.