You are here

Nature of Central Kazakhstan.

Geographic tours in Kazakhstan.

“Nature does nothing in vain”

Aristotle.

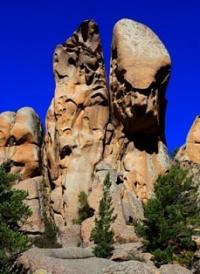

Gorge in Kazakhstan.

Central Kazakhstan occupies the space of the steppe and semi-desert zones within two large orographic and geomorphological units: the Turgai Plateau in the west and the Kazakh lowlands in the center and in the east. The physical-geographical differentiation of the territory of Central Kazakhstan is determined by the intersection of the latitudinal zonal boundaries with the meridional geological geomorphological location dividing the Turgai Plateau and the Kazakh low-hill source.

Turgai Plateau.

Is located between the Southern Urals and the Mugodzhars in the west and the Kazakh Upland with uplifts of the Kokshetau Mountains and the Ulytau Mountains in the east. In contrast to the mentioned neighboring territories, where folded Paleozoic structures mainly come to the surface, the Turgai Plateau is a platform formation with a relatively deep occurrence of the Paleozoic basement.

Tectonically, it corresponds to the complex faults of the Turgai Plateau, which connects the West Siberian plate with the Turan plate, and the northern ledge of the Turan plate. In the middle of the described area, almost in the meridional direction, there is a reduced narrow strip extending to the south.

This is the Turgai hollow. The absolute heights here are 100-125 m. Numerous lakes stretch along a hollow with a large lake Kushmurun in the north, into which the Ubagan River flows, in the south the hollow flows the Turgai River. At the bottom of the trough there is a cover of ancient alluvial and lake alluvial sediments.

To the west and east of the Turgai Hollow, the heights rise to 200, sometimes to 300 meters above sea level. The surface is composed of horizontally deposited layers of Paleogene and Neogene deposits. Paleogene (Oligocene) is represented by marine sediments, mainly saline clays, and lake alluvial sediments, Neogene (Miocene) - mainly continental sands.

The northern part of the Turgai Plateau is weakly dissected. It is characterized by low hills and ridges, shallow lake basins. South of the plateau is dissected by a system of hollows into isolated table elevations. Some of them are lowered and turned into flat outcrops, which are only a few tens of meters above the flat ravines.

The lowland plain has a network of ravines and wide valleys of drying out rivers, gentle depressions in which salty lakes lie. It is believed that the dismemberment of the plateau of the surface on a hill occurred as a result of increased erosion in the period with a more humid than now, climate, corresponding to the era of maximum glaciation in the north of Eurasia.

Later, under conditions of a sharply continental dry climate, processes of deflation and ravines of the dismemberment of the edges of the table elevations developed.

Kazakh low mountains.

Which occupies a vast area to the east of the Turgai Plateau, is an elevated undulating plain with separate low mountain ranges. This is a territory with a surface occurrence of the Caledonian folded complex in the west and the Hercynian in the east.

In the hypsometric relation, the Kazakh low hills are clearly divided into two parts - the western and the eastern (the border between them is approximately at 72 ° E). The western part, extended in the meridional direction over a distance of up to 950 km, has average absolute heights from 300 to 500 m. a. s. l. and is characterized by a more even relief.

There are only two low mountain ranges: Ulutau in the west and Kokchetau (Kokchetav Mountains) in the north. The highest point of the Ulutau massif rises to 1133 m, the mountains of Kokshetau reach 947 m. The eastern part, extending from north to south for 350 – 400 kilometers, is distinguished by high absolute heights (on average, from 500 to 1000 m) and more dissected relief.

The Karkaraly Mountains (up to 1403 m), the Kyzyltas lowlands with the Aksoran massif 1565 meters high above sea level - the highest point of Central Kazakhstan, rise in the center of the mountain. Low mountain ranges are surrounded by small hills.

In the Proterozoic and early Paleozoic on the territory of the Kazakh Hills there was a part of the vast Ural-Tian-Shan geosynclinal region. At the end of the Lower Paleozoic, as a result of the manifestation of Caledonian folding in the west of the territory, a rigid folded boulder was formed, while in its eastern part the geosynclinal mode was maintained.

Only by the end of the Paleozoic, as a result of the Hercynian orogenesis, the eastern part also turned into a folded massif. Since that time, the entire Kazakh low-rise area acquired a platform mode and entered the continental period of development.

Both Caledonian and Hercynian foldings were accompanied by the formation of uplifts, depressions, bends, faults along which uplifts occurred. At the same time, volcanic activity developed, which caused a strong metamorphism of Paleozoic deposits.

Hercynian highland country was already strongly raised to the Mesozoic, and later turned into residual low mountains. The processes of erosion and denudation developed in a warm and humid climate of the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods.

he sea penetrated the margin of the country in the Paleogene along the deflected areas, which developed the plains and left the marine sediments. During the Alpine orogenesis, raising and lowering of certain parts of the territory took place, which complicated the relief and in areas of the latest tectonic uplifts led to its rejuvenation.

The territory of the Kazakh Upland consists mainly of heavily deployed metamorphic schists, quartzites, sandstones and limestones of Precambrian and Paleozoic, sometimes, especially in the west, covered by a thin cover of Cenozoic sediments.

Paleozoic sedimentary rocks are broken by various age, mainly granite intrusions, as well as diorite, gabbro, etc. Structurally tectonic, the Caledonian folded zone of the western part of the upland is an alternation of arrays and internal depressions.

The cores of the large massifs (Kokshetau and Ulytau) consist of metamorphic rocks of the Archaean and Proterozoic, parts - from the Lower Paleozoic deposits. The elevated areas of the territory are confined to the massifs. The depressions (Tenizskaya, Dzhezkazgan, etc.) are made up of younger Paleozoic sediments (Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian) and correspond to relatively flattened and lowered areas.

The largest anticlinoria of the Hercynian folded zone (Chingiz and others) have rocks of the Lower Paleozoic in the core, and their parts are composed of Silurian and Devonian. Large synclinoriums (Karaganda, North-Balkhash) are also located here.

They are made of powerful volcanic and sedimentary strata of the Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian. Intrusions and effusions are widely developed. The abundance of intrusions and effusions determines the wealth of the Kazakh Hills with minerals, especially ore.

Deposits of gold, chromium, nickel, titanium magnetite and other ores are associated with the Caledonian intrusions. Hercynian intrusions of various chemical composition - from ultrabasic to the most acidic - differed in special capacity, which contributed to the formation of various minerals, especially copper, lead, molybdenum, iron, gold, tungsten, etc.

The Paleozoic stage of development is associated with the formation of the largest coal deposits (Karaganda, Ekibastuz). Three main types of relief can be distinguished on the territory of the Kazakh Upland: lowlands, lowlands, and plains.

Low mountains cannot be considered simply as remnants of a denudated mountainous country.

They correspond to areas of extensive modern uplifts - neoctectonic-formed anti-insinoria. The axes of these anticlinoria have a wavy profile, which makes the hills intermittent. The absolute heights of the lowlands are 1000 – 1500 m, and the relative heights usually do not exceed 500 – 600 m.

Nevertheless, the elevated massifs have typical mountainous terrain with a strong dismemberment. Steep rocky slopes, scree, various forms of weathering are characteristic. The orientation of the ridges is usually associated with the strike of rocks.

An example of this is the Karkaraly Mountains; this is a vast highland consisting of numerous isolated arrays composed of granites, porphyrites and quartzites. The northern slopes of the mountains are steeper than the southern ones, richer in springs and vegetation.

Chingiztau Ridge is also an anticlinorium, steeply terminating to the northeast and descending to the southwest in steps. Separate parts of the Ulytau massif and the mountains of Kokshetau have a similar character. Most of the territory of the Kazakh Little Hills is occupied by the Hillside proper, on all sides surrounding arrays of lowlands (the Hills are called an elevated undulating plain, in which numerous hills and ridges of indigenous sediments with a relative height of 15 - 60 m are located in rows or randomly).

Small hills, ridges and ridges are riddled with a dense network. Their flattened tops are complicated by rocky overhangs. Small-scale arrays are divided by ancient and modern hills of the valley into separate sections. In some places there are closed basins with lakes and salt marshes.

The morphological features of the land are associated with structural and lithological conditions. Quartzites give sharp rocky protrusions, in granites there are peculiar separateness, etc. The slopes of the hills are mostly gently sloping due to the abundant accumulation at their feet of gravelly debris, in which the hills seem to be buried.

This is a consequence of the influence of the modern dry continental climate, contributing to intense physical weathering. Weathering products outside the Kazakh Hills is difficult due to the small amount of precipitation. Formerly, the low-top boiler was taken for an almost typical peneplain.

Now it is not considered as the final stage of the relief alignment, but as a result of recent tectonic uplifts, deformations and dismemberment of the ancient peneplain. The watershed small hill formed due to the dismemberment and erosion of the socle plains with the ancient weathering crust.

These socle plains are witnesses of the early stage of the relief of formation - the stage of peneplanation. The low hills are the product of the subsequent stage of development of the relief - the stage of peneplain destruction. The tops of the hills correspond to the hypsometric levels of ancient leveling surfaces. In addition to the surface, fixed by the ancient crust of weathering, there are several more such levels.

Their formation is associated with tectonic oscillations. Characteristic are broad (from 3 to 20 km) ancient valleys, which now have dry channels. Their width indicates that in Neogene, in a more humid climate, erosion activity manifested itself much more intensively than it is now.

However, most of the ancient valleys are now buried under sediment. Modern river valleys in many cases inherited ancient valleys and are also characterized by a considerable width. The development of wide valleys contributes to the extreme irregularity of the runoff with a pronounced spring maximum caused by the melting of snow.

The eastern part of the Kazakh Upland is a classic area of low-rise relief. To the north and to the west, the typical low-slope turns into weak undulating plains with mountainous island elevations scattered here and there. The formation of these plains is associated with the lowering of certain parts of the territory and the flooding of the Paleogene

Sea with their waters, the abrasion of which and the accumulation of marine sediments smoothed out the irregularities of the Mesozoic topography, forming aligned spaces. In the west of the Kazakh Upland, the erosional erosion under tectonic uplifts of the beginning of the Quaternary period led to the formation of the riverside upland upland - strips of dissected relief, confined to the indigenous banks of river valleys.In the north of the Turgai Plateau and the Kazakh Hills are mainly spread steppe landscapes, forming together with similar landscapes of the south of the West Siberian Plain steppe zone.

To the south, the space of the Turgai Plateau and the Kazakh Hills is occupied by a semi-desert zone. The southernmost part of the Kazakh Upland belongs to the northern desert zone.

Steppe zone within Central Kazakhstan.

The northern, weakly dismembered part of the Turgai Plateau, as well as the northern and middle parts of the Kazakh Upland belong to the steppe zone. The remoteness of the steppes of Central Kazakhstan from the oceans, especially from the Atlantic - the main supplier of moisture in these latitudes, causes a sharp continental climate, which is expressed in the severity of winter, high summer temperatures, short duration of spring and autumn, large annual and daily amplitudes of air temperature, dry air, low rainfall.

Rainfall varies greatly from year to year, averaging around 300 mm per year. In the north, it is somewhat larger (up to 350 mm), towards the south it gradually decreases (up to 200 mm). Mountain ridges stand out with the best humidification, with about 400 mm of precipitation a year.

Along with a decrease in precipitation in a southerly direction, air temperature increases, evaporation increases, and summer moisture deficit increases. The features of the cold period of the year are due to the existence of a high-pressure spur (departing from the Asian anticyclone), whose axis extends approximately 50 ° C each. sh., i.e., it divides almost in half the territory of the Turgai Plateau and the Kazakh Upland.

The average January temperature is rather low (- 17 - 18 °). Temperatures fall toward the center of the anticyclone; therefore, the eastern regions are the coldest in winter. In winter, cold masses of arctic air and air of temperate latitudes with a small amount of moisture predominate.

Frontal activity is weak. There is little precipitation (from November to March only 50 - 75 mm). Snow cover has a small thickness (medium - up to 40 cm), which leads to soil freezing; and yet snow is the main source of moisture in the soil, as well as the supply of rivers, lakes and groundwater, since summer precipitation is almost entirely spent on evaporation.

In winter, in the steppe zone, southwesterly winds dominate, reaching great strength, which is facilitated by the vastness of the lowland spaces. Characterized by winter storms and snow drifts. The transition from winter to summer is sharp.

The air temperature is rapidly increasing due to the warming of the earth's surface and the penetration of warm Turanian air from the south.

The winter anticyclone is destroyed, and high summer temperatures are established (the average temperature in July is 20 - 24 °). Daytime temperatures in summer sometimes rise to 35 °. In the warm season, from April to October, up to 250 mm of precipitation falls, with a maximum in June.

By the middle of summer, the air masses become very hot and the temperature differences between them smooth out, the frontal activity weakens, there is little precipitation; during almost the entire second half of the summer, the clear, sunny anticyclonic weather is preserved.

Strong winds of the warm half of the year cause ground wave, dust storms and contribute to the overall desiccation of the territory. Often there are droughts. The invasions of cold air masses from the West Siberian Plain cause spring and autumn frosts.

The frost-free period is about 110 days. Compared with the surrounding plains, the arrays of the lowlands have a more temperate and humid climate, which, with a small range of heights, determines the high-altitude zoning of landscapes, the formation of the forest-steppe high-altitude zone.

Microclimatic differences are characteristic of both low mountains and low-slope plains due to the dismemberment of the relief. On summer days, the lowest temperature is usually observed on the tops of the hills, while in the lowlands it is the warmest.

True, the difference in temperatures at this time is small. In the periods of spring and autumn frosts in the skull depressions, due to radiation cooling, runoff and stagnation of cold air, it is 8 – 9 ° colder than on the tops of the hills with altitudes up to 80 – 100 m.

In the steppe zone of Central Kazakhstan, non-irrigated farming is possible. The temperature conditions here are mostly favorable for the development of agricultural plants. Moisture conditions are much less favorable, both in terms of precipitation and their distribution by seasons.

Therefore, the main crop here is wheat, which is quite resistant to drought (due to winter freezing of the soil spring wheat is cultivated). Millet, corn, barley, oil flax, and sunflower also grow well. The steppe zone of Central Kazakhstan mainly belongs to the Irtysh basin, and only the Nura River in the very south of the zone, carrying its waters into the Tengiz Kurgaldzhinskaya depression, belongs to the Central Asian region of internal flow.

True, many rivers rushing to the Irtysh do not convey their waters to it and end in small closed lakes in the south of the West Siberian Plain. Due to the continentality and dryness of the climate of the river is shallow. Most of them dry up in summer or break up into ridges connected by an underground stream in river alluvium, and only the largest ones (Tobol in the far northwest, Ishim, Nura, Shiderty, Selty) retain water throughout the year.

Drain mode lawsuit the rivers of Central Kazakhstan are not navigable, but are of great importance as a source of water supply. There are many lakes on the territory of the Kazakh High Mountain Range and the Turgai Plateau within the steppe zone (Kushmurun, Koibagar, Karasor, a group of Kokchetav and Borovskiye lakes).

The origin of lake basins varied. There are basins of tectonic origin. There are small sedimentary basins. Small lakes are widespread, formed by streams of water flowing from the slopes of the hills. Many lakes in the river valleys. According to A. E. Mikhailov, part of them originated in river valleys crossed across by tectonic uplifts with anticline folds.

The river erosion weakened in the conditions of arid climate could not saw through the obstacles that had arisen. Lakes, as well as rivers, receive the main power in the spring due to the melting of snow. In the summer they become shallow. Fluctuations in the level of lakes are associated with fluctuations in precipitation.

The degree of mineralization of lake waters varies with seasons, reaching a maximum in summer. Many lakes gradually become shallow and overgrown. There are so-called grass lakes, only in spring they fill with water, and in summer they are used as hayfields.

Various salts are mined in lakes, in some places - curative mud. Rivers and lakes due to the extreme unevenness of the regime cannot serve as a reliable source of water supply. However, on the rivers it is possible to build artificial reservoirs fed by the discharge of melted snow water.

There are two types of groundwater in the Kazakh Hills: fracture and reservoir, and at the Turgai Plateau - reservoir. Fissure waters are confined to Paleozoic rocks. Their abundance is due to the presence of tectonic faults. The most abundant granitoids and limestones.

Limestone strata contain cracks karst and karst waters, especially characteristic of limestone of Upper Devonian and Lower Carboniferous. Nutrition of fissure waters is carried out mainly due to infiltration of thawed snow waters, therefore the maximum costs are observed in spring, and in the rest of the year the expenses of sources fall.

Freshwater is quite suitable for use. Filtered through gravelly sediment, water can salty. The steppe zone is divided into two zones: forb grass cereal chernozem steppes and grass steppes on dark chestnut soils. Under the zone, the forb grasses of chernozem steppes occupy the northernmost part of the Kazakh Hills and Turgai Plateau.

High summer temperatures cause a large loss of moisture to evaporation, which causes a significant dryness of the soil. In the Kazakh Upland, the dryness of the soil is aggravated by the rubble of soils that easily filter moisture. Only in the north, in the Kokchetav province of Central Kazakhstan, ordinary chernozems are common, while the main background of the soil cover of the zone is formed mainly by carbonate southern chernozems, which are formed under forb grass fescue communities.

Within the zone of dry steppes in the Kazakh small mountain area, the phenomenon of altitudinal zonality is also observed. On the rocky tops of lowlands, pines grow with grass from steppe species. Near groundwater outcrops there are aspen birch groves.

Gentle slopes are occupied by mixed grassy steppes on mountain black soil, with a predominance of red grass. The fauna of the steppe zone contains many rodents: a large ground squirrel (Citellus major), a large jerboa (Allactaga jaculus), a hare (Alactagulus acontion), (Scirtopoda telum), a little hare (Ellobius talpinus), various voles (Microtus gregalis) and others.

There are wolf, fox, badger, weasel, ermine and such typical steppe species as the step ferret (Putorius eversmanni) and Vulpes corsac). Of the birds, the bust (Otis tarda) is particularly characteristic. The semi-desert zone occupies the southern, more dismembered part of the Turgai Plateau and a wide strip of the Kazakh lowlands in its southern part, with the exception of the southernmost margins.

In the north, along the Turgai hollow, the semi-desert zone is wedged into the steppe zone due to the spread of saline Paleogene deposits here. The exceptional wealth and diversity of mineral resources of Central Kazakhstan contribute to the rapid growth of industry, which, however, was hampered by the lack of drinking and industrial water.

The problem of water supply is resolved by the creation of the Irtysh-Karaganda canal with a total length of 458 km. Starting 30 km south of Pavlodar, it goes west through Ekibastuz to the river Shiderty, from where pumping stations supply water up the river Shiderty, through its watershed with Nura, into the valley of the Tuzda river, to Temirtau and Karaganda.

The canal provides guaranteed water supply to large industrial areas of Central Kazakhstan - Ekibastuz, Karaganda-Temirtau, provides water for regular and estuary irrigation of land, which allows increasing the production of vegetables, potatoes and animal feed.

The Nura-Ishim Canal is filled with Irtysh water. Groundwater will continue to play a major role in water supply in Central Kazakhstan. There are large masses in the steppe zone of Central Kazakhstan.

Authority:

N. A. Gvozdetsky, N. I. Mikhaylov. "Physical geography of the USSR. Asian part. The edition third corrected and added. Moscow "Thought" of 1978. http://tapemark.narod.ru/geograf/1_5_5.html

Photos by

Alexander Petrov.