You are here

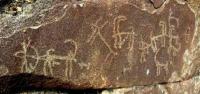

Cave paintings of Ghissar-Alai.

Cave paintings and Petroglyphs Tajikistan.

“He who conquers himself is the mightiest warrior”

Confucius.

Ancient Petroglyphs of Tajikistan.

The Hissar Alai range system associated with Southern Tien-Shan is the most important in Tajikistan. It is bounded by valleys: the Fergana Valley in the north, the Hissar Valley, Sukhrob River Valley and Alai River Valleys in the south.

The Hissar Alai Range system stretches from east to west for about 900km. The height of most peaks exceeds 5,000m. The main Hissar Alai mountain ranges include the Turkestan, Zeravshan, Hissar, and Alai Ranges that stretch in latitudinal and sublatitudinal directions.

The eastern part of the Hissar Alai is in Kyrgyzstan, its western part in Uzbekistan, while its middle is located within Tajikistan. The Karategin Range branches off the Hissar Alai Range. The system of the Hissar Alai Ranges towering over valleys is a nearly impassable barrier that divides the territory of the republic into two parts – northern and southern.

The Alai Range stretches for almost 200km and forms the eastern part of the Hissar Alai Range; it is mainly in Kyrgyzstan, while only its small western part is in Tajikistan. Near the upper reaches of the Zeravshan River, near the Matcha pass, the Alai Range divides into two mountain chains - the Turkestan and Zeravshan Ranges.

The Turkestan Rangestretches for 200km between the Fergana and Zeravshan valleys. Its highest point is in the eastern part (Piramidalniy Peak, 5,620m), then the range gradually recedes westward and ends in the Nuratau Mountains in Uzbekistan.

The Zeravshan Range stretches almost in parallel with the Turkestan Range. The Zeravshan River cut its way between the two. It now flows in a deep gorge, with sections of basin-like expanses and terraces. Landslides in the Zeravshan Mountains often cause temporary lakes.

The Zeravshan valley begins to widen and floodplains and large terraces fit for agriculture appear downstream at the mouth of the Kshtut River. The Zeravshan Glacier, considered as the largest in Tajikistan, is located in the upper reaches of the Zeravshan River.

The ridge of the Zeravshan Range is rocky. Absolute heights there exceed 5,000m. In contrast to the Turkestan Range, which is a continuous mountain ridge, the Zeravshan Range is cut through in 3 places all the way down with the valleys of the left tributaries of the Zeravshan –Fandarya, Kshtut, and Magiyan.

A section of the range between Fandarya and Kshtut called Fan Mountains is distinguished by the complexity of its structure and its immense height (Chimtarga 5495 m). The eastern section of the Zeravshan Range is named Matcha Range, and the western Chakyl-Kalan.

The Hissar Range branches off from the Zeravshan Range in the upper reaches of the Yagnob in the complex of mountains Barzangi and forms an interstream area between the Amudarya and Zeravshan River valleys.

The highest point in the eastern and middle parts is 4,688m above sea level, while the range gradually recedes south-west crossing to Uzbekistan and turns into low ranges. The total length of the Hissar Rangewithin Tajikistan is about 250km.

The slopes of the Hissar Range have many glaciers. Many convenient passes cross the Hissar Range, the Anzob pass (3,372 m) being the most important. Prevailing Types of Landscape Concentrations of petroglyphs in the Hissar Alai are associated with various landscapes.

The localization of key sites depends upon the gorges in the upper reaches of the Zeravshan River, where they are concentrated along the riverbanks. The greatest number of rock art sites is known in the Fan Mountains, on cliffs of the Magian-Darya River, in the Iskandar River basin, on the left bank of the Kshtut-Darya and Shing-Darya Rivers.

Concentrations of petroglyphs are known at the openings of the gorges of Say Gurbic, Say Vagishton, Say Mosrif, and Soyi Sabag. Insignificant sites were registered in the vicinity of the settlements of Padask, Khudgif, and Esizi Poen.

Petroglyph sites are found in the Zeravshan River Valley, including petroglyphs west of the village of Shamtich. About 200 images were engraved on large and small dark-brown boulders in the proximity of old and new cemeteries

located on a smooth 300 х 100m terrace at the foot of the Turkestan Range on the right of the Zeravshan. A famous inscription by Babur is incised in nastalik handwriting on the surface of one boulder and consists of two rhyming lines in the Tajik language.

About 300 petroglyphs were registered 300m downstream as well as on the terrace to the left of the river in a locality known among locals as Dashti Mullo Tokhiriyon. Predominantly, images of goats are carved in a linear style; there are hunting scenes, archers and an elephant. In general, Shamich and Dashti Mullo Tokhiriyon petroglyphs are similar.

Quantity and Distribution of Sites The Hissar Alai group includes 50 known sites with petroglyphs carved on rocks and individual large boulders both in the valleys of the Zeravshan River tributaries and in sidelong gorges.

The most interesting petroglyphs were registered at Gurbic Sai along the Kshtut River as well as in the valley of the Shing River near the villages of Vagishton and Mosrif Gully. Dating The Zeravshan Valley petroglyphs predominantly comprise monotonous reiterations of mountain goats engraved in a “linear” or “skeletal” style.

Most petroglyph sites in the Hissar Alai have images of different periods, Bronze Age images being the most ancient. Large series of Bronze Age petroglyphs dated to the 3rd – 2nd millennia BC are found in Vagishtan Sai and Soyi Sabag.

Drawings in concentrations at Shamich and Dashti Mullo Tokhiriyon are dated to the Early Middle Ages and the Medieval Period. Archeological Context Archeological research in the upper reaches of the Zeravshan River helped discover several Bronze Age sites and many sites dated to Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages.

Early periods are represented by an ancient farming settlement, Sarazm (Eneolithic – Bronze Age) and burial sites of the Bronze Age: Dashti Kozy, Zardcha Khalifa, and Zoosun. Settlements and fortresses are the most numerous and date to the Early Middle Ages and the Medieval Period.

The upper reaches of the Zeravshan River contain rich deposits of complex ores, including ornamental, high-quality silicon and clay that have been used since ancient times for implements, weaponry, and household objects.

Deposits of fluoride and tin (Kaznok), amethyst (Manor Gully), sodalite (Sabag Gorge), almandite (valleys of rivers Samjon and Turo, Iskandardarya River basin), marble (Mosrif, Kosatarosh, Voru, Mazori Sharif, Tillagul Gullies), copper, silver, and gold (Taror), lead, copper, and zinc (Kangut mine) and others are found in the foothills of the Zeravshan and Turkestan Ranges (Razzakov 2008), most of them in the vicinity of well-known petroglyph sites.

Most images of objects, ornamental motifs, animals, etc. in the repertoire of the most ancient Zeravshan petroglyphs are similar to those on artifacts found in the ancient farming settlement of Sarazm, dated to the Eneolithic and Bronze Age (Isakov 2005).

The Modern Ethno-Cultural Context No traditions of specific worship or reverence toward rock art sites were identified.

Authority:

Bobomullo S. Bobomulloev.

Photos by

Surat Toymasov.