You are here

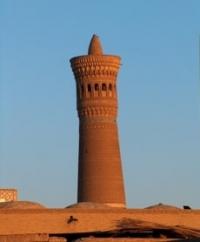

Kalon Minaret in Bukhara.

Excursions on minarets in Bukhara.

“I've known rivers:

I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers”

Langston Hughes.

What to see in Bukhara.

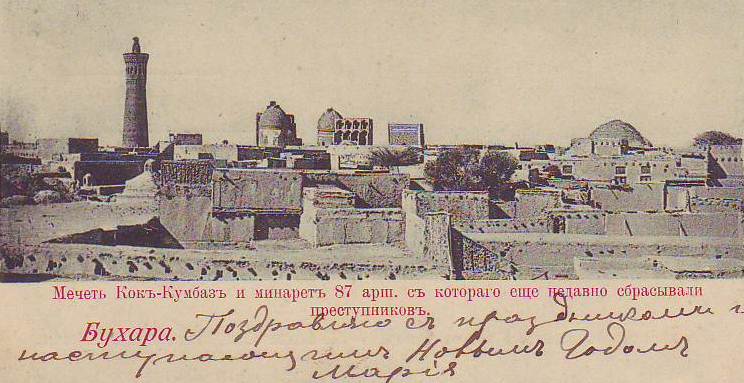

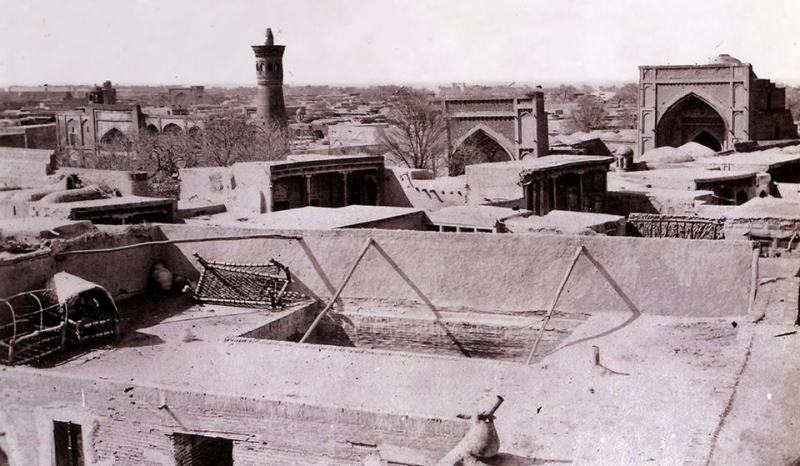

The road from the Registan to the Kalon minaret; its north side is now being rebuilt as a tourists' bazaar. No-one is allowed to re-name or rebuild the minaret (though its nick-name is the Tower of Death) because it is on the UNESCO world heritage list.

There is trial and error behind its longevity. The first minaret here was wood-framed, and burned down. The second, built early in the Karakhanid Arslan Khan's reign, was of brick but after 'someone bewitched it with an evil eye' it fell on and largely demolished the adjacent mosque.

Second time round Arslan Khan took no chances. His survive colossus is nearly 14 metres wide at the bottom and has cubic foundations 10 m deep. At 47 metres high, it was probably the tallest building in the world when completed in 1127.

The idea may have been for its 16-arched brick lantern, from which the people were called to prayer, to be on a level with Samarkand 250 km away. It was certainly used as a light, house for caravans travelling at night-a fire would be lit in the lantern-and can still be seen from miles out on the flat approaches to Bukhara.

There are 14 bands of kufic calligraphy round its tapering neck (one names the architect as 'Bako'), interspersed with as many bands of decorative brickwork, all of them different. The turquoise 'necklace' at the top is the first use of glazed tiles in Central Asia.

When Genghis Khan spared this building he was probably as impressed by its punitive potential as its height. He and subsequent khans threw people off it, faithless wives as well as common criminals, hence the name 'Tower of Death'.

Dates the last death by jaculation 1884, but escaped Austrian POW Gustav Krist claimed the tower still served this purpose in the 1920. Nor was anyone else in pre-Soviet times, except the khan; it was too good a vantage point for spying on womens' balconies.

From the beginnings of Islam, there have been three types of mosques: Djuma mosques, which are intended for the large crowds that come to Friday services, Namazga country mosques (musalla idgoh), which are used by the male population of both the city and the surrounding countryside to celebrate the two Muslim holidays Qurban and Ramazan, and Quzar mosques, which are designed to be used as daily mosques in residential neighbourhoods.

We know very little about the thirteenth century Djuma Mosque in Bukhara, for it has been rebuilt completely since the time of its original construction. In any case, it had a vast courtyard surrounded by galleries.

However, the minaret which was built in 1127 A.D. and called the Kalyan (Great) Minaret, has survived. It still dominates the skyline of Bukhara, astonishing all who see it with its magnificent and flawless shape.

The minaret was designated to summon Muslims to prayer five times a day. Normally, each mosque had its own minaret, but the main minaret was situated near the Djuma Mosque. It was from the gallery, at the top of the minaret, that the muedzin summoned the believers to prayer at the top of his voice.

The Kalyan Minaret was built twice. The fact is it collapsed just before it was completed the first time, probably because of the builders did not take into account the soft ground underneath, due to the many cultural layers beneath the city.

A new, more durable foundation was laid for the minaret and, by 1127, construction of this second minaret was completed. According to someone writing at the time, «there was nothing like this minaret, for it was built very beautifully». Indeed, the forty-eight m tall Kalyan Minaret is a flawess example of both civil engineering and superior architectural creation. The baked bricks it is made from form a monolithic circular tower that narrows from its thick base to its top.

The body of the minaret is topped by a rotunda with 16 arched fenestrations, from which the muedzins gave the call to prayer. In times of siege or war, warriors used the minaret as a watchtower.

Earlier, the minaret apparently had another round section above the rotunda, but now only the cone-shaped top is left. The baked bricks, from which the minaret is made, are the main feature of its architectural design.

The body of minaret is belted with narrow ornamental strings made of bricks. They are arranged in a chessboard order, either straight or diagonally. A frieze with inscriptions goes around the minaret upon a muqarnas (stalactite) cornice.

The frieze is covered with blue glaze, which was used widely in the architectural decor of Bukhara at that time.

Authority:

V.G Saakov «History of Bukhara». Publishing house "Shark", 1996. «Bukhara. Masterpieces of the Central Asia». The historical guidebook across Bukhara. 2012. "Bukhoro. Bukhara" In the Uzbek, English and Russian languages. Publishing house "Uzbekistan", Tashkent 2000. Mukhammad Narkshakhi. History of Bukhara. Tashkent. 1897 (translator N.Lykoshina). V.G.Saakov "Architectural masterpieces of Bukhara. A Bukhara regional society "Kitabhon" Uzbek SSR, Exactly 1991 Robert Almeev. "History of ancient Bukhara". (Under edition of the Academician of the Academy of sciences of Republic Uzbekistan of Rtveladze E.V.)

Photos

Alexander Petrov.