You are here

Travel of Silantyev on Altai.

Trip to Rakhmanovskiy lake.

“Of course, I could be wrong, but in any case, the Sharypovs and Lubyagins, according to the opinion of all Bukhtarmins, are the oldest maralovod farms in Altai, not Chernovy in Upper Uymon, which they do not deny. That maral breeding originated in the Fykalka near the Sharypovs”

A.M. Nikolsky. 1882.

Bukhtarma Valley Tours.

There are great trips that brought worldwide fame to their participants, and everyone knows them. These are the expeditions of N.M. Przhevalsky, who discovered the nature of Central Asia to the world. And there are very small travel trips, maybe even business trips, known to a small circle of specialist scientists, but they also contributed to science, and it would be interesting to recall them.

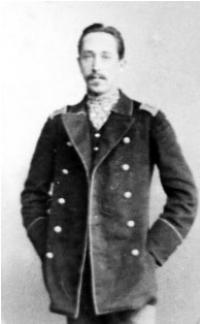

Such was the trip to Altai in 1897 by the privat-docent of the St. Petersburg Forest Institute, the famous biologist and hunting expert Anatoly Aleksandrovich Silantiev, who he made on behalf of the Ministry of Agriculture to study the status of deer farming.

In those years, maral breeding was in its infancy. Only 60 years have passed, when quick-witted Russian peasants were the first in the world to guess not to kill wild deer because of healing horns, but to keep them in a half-witted state.

Thus, a whole livestock industry was born, and the Russian Ministry of Agriculture noticed it, evaluated and sent a specialist, a scientist, to study the problems of a valuable industry on the spot. Silantyev took A. Serebryanikov, a student at the Forest Institute, as an assistant, especially since the Zoological Museum (now ZIN AN) ordered Silantyev to collect faunal material, allocating 300 rubles for this purpose and equipping it with the necessary tools and accessories.

1897, the end of the XIX century. Just two years ago, in order to come to Altai, it was necessary to travel 3 to 4 months and shake in a road tarantass harnessed by horses, every day exposing itself to the risk of catching a cold, together with a wagon, falling into the river under the ice or capsizing on a slope.

Now, with the construction of the railway, the path from St. Petersburg to Novo-Nikolaevsk (now Novosibirsk) was overcome in no more than 6 days. Almost the same speed as on the current railway, although as much as 105 years have passed!

From Novo-Nikolaevsk, Silantyev’s way to the crossroads lay in Barnaul, where the scientist received a warm welcome and all kinds of assistance from the head of the Altai district, Major General V.K. Boldyreva. The traveler also met with no less participation in Biysk, where, thanks to the courtesy of the police officer Golovachevsky, guard Kovalev was seconded to him for protection.

The centers of the then maral breeding were located along the Katun River, in the Uimon Valley, along the Charysh River, but the richest and most numerous maralniks were in Southern Altai, in the Bukhtarma Valley. In addition, Silantyev intended to visit Lake Teletskoye, Chui and Kurai steppes in the Altai Mountains, to go through Argut and Chulyshman.

Thus, a large ring route was planned, covering most of Altai, difficult and even dangerous, for the most part passing through the mountain taiga, where at best there were only trails, and even those completely unfamiliar to travelers.

But travelers were not frightened by the difficulties of traveling through deserted terrain with ferries through turbulent, mountainous rivers; on the contrary, they longed to get to the wildest places in order to test and test themselves and enjoy the beauties of the wonderful Altai nature.

Much more frightened by another. As A. Silantyev himself writes, two formidable ghosts gravitated over them all the time of the trip and poisoned all the pleasure: this was limited in time - they had only two months, July and August, and the scarcity of money, because they had to hire guides, horses, and buy food.

To this was added the lack of a good map, and there was a problem with the conductors who knew all the way. Therefore, all the time I had to solve excruciating questions: did they go so, didn’t they shorten the route, would there be enough money, would they manage to finish the route on time.

Behind Biysk, Mountain Altai began. Moving along the tract, Silantyev examined the maralniks. This survey consisted of collecting statistical data, examining animals and "gardens" (from the word "cage") and "parks", the so-called fenced areas for grazing deer.

The owners of the maralnikov, fearing a trick, answered reluctantly, but when they saw that everything was being done in their interests, they talked, the conversation became relaxed and lively, the maralovods shared their secrets, told cases from the lives of animals, etc.

The scientist was present when shooting horns and took pictures. He did not disdain to participate in the hunt for mountain goats, marmots, especially since he promised to collect zoological trophies (skins, skulls, etc.) for the zoological museum.

At this first stage, Silantyev rode without his companion, Serebryanikov, having lingered on student studies in St. Petersburg, caught up with him in Ongudai. Here the wheel road ended, then the travelers had to leave the carts, load all their luggage on horses and set off for the mountains.

On the way to Uimon, they had to ride on horseback through the snowy Terektinsky ridge, where they spent the night at the upper border of the forest on the Kureges pass. All the way, for at least three days, it rained incessantly, replaced by snow pellets on squirrels with a very strong, cold wind.

Travelers huddled in the cold, but most of all, Silantyev was depressed that because of the bad weather it was impossible to choose a moment for photographing, and many magnificent views remained uncaped. In the Uimon Valley they were examined by local maralniks, put their collections in order:

horns, skins and other things, and having hired 14 horses and two guides for 170 rubles, they divided into two parties. Silantyev himself, with guides and pack horses, decided to inspect the maralniks along the Charysh, and Serebryanikov and Konovalov across Talmenye had to cross the high Katunsky ridge, moving slowly and paying as much attention as possible to collecting zoological material, and then going down to the Bukhtarma valley so that two weeks later, arrive in the village of Altai (Katon-Karagay), where both groups were to meet.

And so it happened. Silantyev, upon completion of work in the Uimon Valley, rose from the village of Abay, crossed over Kholzun, and down the Chernova River valley he went down to the village of Pikhtovka on Bukhtarma.

This time the weather was favorable for the traveler, the sun was shining, everything was going fine, except for the unfortunate occasion when Silantyev, having delayed taking photographs, parted with his companions and got lost in the taiga.

Having lost the whole day, in the evening at the top of the Shikhaliha river he came across a lone apiary. The old beekeeper sheltered him for the night, and in the morning he led him out onto the trail, where they met with guides, who were much frightened for the fate of their boss.

From Pikhtovka, climbing up Bukhtarma, Silantyev examined the maralniks in Sennaya, Korobikha, Pechi, Belaya, Yazeva and Fykalka. Here was the center of all deer breeding in Altai. It was here that this occupation originated and spread from here to all Altai mountains.

According to questions from old-timers, Silantyev wrote down the entire history of the appearance of deer breeding. In time immemorial, having come to Siberia, Russian people were surprised to learn that the Chinese are buying deer horns for a lot of money and especially appreciate the young, those that have not yet become ossified and are called antlers.

Hunting for deer gave a good income. She especially flourished in Altai, where there were many animals and fugitive Russians settled - Old Believers, persecuted by the authorities for faith and workers of the Kolyvano-Voskresensky factories, who fled from overwork in the mines.

And this is understandable: after all, hiding in the wild mountain gorges on Bukhtarm and Katun, it was difficult for them to engage in agriculture or cattle breeding. The sale of antlers gave them the opportunity to live comfortably - to buy food in neighboring Russian villages, and clothes from the Chinese.

However, increased hunting led to a rapid decline in the number of deer, and getting horns became increasingly difficult. “And what if you don’t kill maral, but keep it at home, cutting off healing horns every year?” Came the thought of smart Russian peasants.

The conjecture also led to the fact that often, having killed the uterus, deer calves fell into the hands. It all started with the fact that a resident of the village of Fykalki, Savely Ignatievich Ushakov, in the early 30s of the XIX century, having caught a live bull-deer, began to keep him in his “little garden”.

This bull-calf was bought from Ushakov by Avdey Parfenovich Sharypov, and began to replenish his maralnik with new, wild animals mined in the wild. Having married Yegor Vasilyevich Lubyagin’s daughter from the village of Yazeva, Sharypov introduced his father-in-law to his occupation and, having sold him several deer, laid the foundation for maral breeding in the village of Yazeva.

The work of his father was successfully continued by the sons of Sharypov Roman, Sidor and Athanasius, with whom Silantyev met. Interestingly, the right of priority was disputed by Stepan Semenovich Lubyagin, the grandson of the aforementioned Yegor Vasilyevich. According to him, the grandfather started a maralnik first of all in the village of Yazeva in 1835, and, having betrayed his daughter as Avdey Sharypov, gave several animals to his dowry.

Gradually, other inhabitants of the villages along Bukhtarma (in Korobikha, Yazeva, Belaya, In Pecs and Sennaya) and along Katun, in the Uimon Valley began to contain marals. Having written down these two versions, Silantyev gave preference to the first. The modest and modest Sharypovs aroused more confidence in him than the young Lubyagin, who was cheeky and impudent, who spoke the ornate-seminarian language and imagines himself a descendant of the first maralovod.

“Of course, I could be wrong, but in any case, the Sharypovs and Lubyagins, according to the opinion of all Bukhtarmins, are the oldest maralovod farms in Altai, not Chernovy in Upper Uymon, which they do not deny. That maral breeding originated in the Fykalka near the Sharypovs, AM also reported. Nikolsky in 1882. " (A. Nikolsky - a learned biologist who traveled to Altai in 1882 - A.G.).

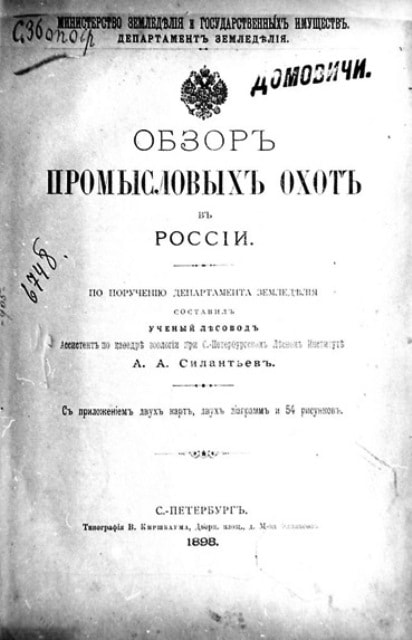

So Silantyev himself wrote in his book “Research on deer breeding in Altai,” published in St. Petersburg in 1900. In the same place he gives figures on the state of maral husbandry of that time. Without going into details, we cite only two of them: from 201 maralnik in Altai and 6280 maral, in the Bukhtarma basin there were 115 maralniks with 3641 maral (together females and males).

On August 4 in the morning, Serebryanikov’s detachment arrived in Katon-Karagay and pitched near the village, and in the afternoon Silantyev arrived from Fykalka there. Serebryanikov’s detachment was delayed a little due to the intention to get the Altai black groundhog, which until now had not been given to scientists.

Only with great efforts, after lying near the hole for about three days, it was possible to shoot and get two large and one small animal, and the difficulty was that the wounded animals fell into their holes between the stones, from where it was not possible to pull them out.

Having met safely, the whole expedition the next morning drove up Bukhtarma to the village of Chernova, where they made a halt for several days in an empty apartment, kindly provided by its owner M.I. Oshlykovym. Here, arranging their gatherings and diaries, the participants of the trip lived 4 days, and on August 10 they set off on their further journey to the village of Berezovka, and from there to Berel - the last deer breeding point on Bukhtarma.

By August 15, the inspection of Bukhtarma’s maralniks was over; all that remained was to get through the mountains to Ulalu, a village in Northern Altai, where there were few maralniks and, thus, the business part of the expedition was almost completed, but the most difficult and most interesting part of the trip through the Rakhmanovs remained ahead keys, highlands, with the intersection of the rivers Argut, Karagem through the spurs of the South Chuy and Severo-Chuy ranges.

As Silantyev himself writes, “For two weeks from August 15 to September 1, we, not being distracted by any duties, completely indulged in contemplation of the most charming, grandiose pictures of mountain nature, preserved in virgin purity, and during this time we waved more than a third of our entire journey through Altai, landed September 1 on the northern shore of Lake Teletskoy".

But how many dangerous adventures, difficulties, hardships, minutes of despair had to endure along the way! At times, it seemed that there was no way out, and despondency took possession of the travelers. After a many-day journey from the Rakhmanovskie keys, we reached the Karagem river, which flows into Argut.

It rained for two days, everyone got wet, the tents were leaking, piercing wind and dampness did not allow to light a fire. But most importantly, it turned out that the Russian guides did not know the further path, the Kalmyks (Altaians) encountered along the way scattered, the horses knocked down their legs and could not go any further.

What to do? The easiest way would be to get to Ongudai, where the wheeled road began, and from there to Barnaul. But then, forgiving the dream to go to the most interesting places in Altai, to see Lake Teletskoye, collect zoological material and information about local maralniks there.

And then Silantyev decided to find the Kalmyk Bosko, something like a centurion, the Altai elder, convene a council and try to find the Altai guides. So they did. They found two Altai people, and they brought Bosko. But he found himself drunk to death, and besides, none of the Altai people knew the Russian language, and travelers did not know the Altai language. However, with the greatest difficulties everything worked out, found guides, hired fresh Kalmyk horses and set off.

For five days travelers traveled with guides who did not know a word in Russian, but on the other hand, they completed the entire plan and saw the most beautiful part of Altai. Thus ended the fascinating and very necessary journey of Silantyev to Altai.

Having written down these two versions, Silantyev gave preference to the first. The modest and modest Sharypovs aroused more confidence in him than the young Lubyagin, who was cheeky and impudent, who spoke the ornate-seminarian language and imagines himself a descendant of the first maralovod.

“Of course, I could be wrong, but in any case, the Sharypovs and Lubyagins, according to the opinion of all Bukhtarmins, are the oldest maralovod farms in Altai, not Chernovy in Upper Uymon, which they do not deny. That maral breeding originated in the Fykalka near the Sharypovs, AM also reported. Nikolsky in 1882. " (A. Nikolsky - a learned biologist who traveled to Altai in 1882 - A.G.).

So Silantyev himself wrote in his book “Research on deer breeding in Altai,” published in St. Petersburg in 1900. In the same place he gives figures on the state of maral husbandry of that time. Without going into details, we cite only two of them: from 201 maralnik in Altai and 6280 maral, in the Bukhtarma basin there were 115 maralniks with 3641 maral (together females and males).

On August 4 in the morning, Serebryanikov’s detachment arrived in Katon-Karagay and pitched near the village, and in the afternoon Silantyev arrived from Fykalka there. Serebryanikov’s detachment was delayed a little due to the intention to get the Altai black groundhog, which until now had not been given to scientists.

Only with great efforts, after lying near the hole for about three days, it was possible to shoot and get two large and one small animal, and the difficulty was that the wounded animals fell into their holes between the stones, from where it was not possible to pull them out.

Having met safely, the whole expedition the next morning drove up Bukhtarma to the village of Chernova, where they made a halt for several days in an empty apartment, kindly provided by its owner M.I. Oshlykovym. Here, arranging their gatherings and diaries, the participants of the trip lived 4 days, and on August 10 they set off on their further journey to the village of Berezovka, and from there to Berel - the last deer breeding point on Bukhtarma.

By August 15, the inspection of Bukhtarma’s maralniks was over; all that remained was to get through the mountains to Ulalu, a village in Northern Altai, where there were few maralniks and, thus, the business part of the expedition was almost completed, but the most difficult and most interesting part of the trip through the Rakhmanovs remained ahead keys, highlands, with the intersection of the rivers Argut, Karagem through the spurs of the South Chuy and Severo-Chuy ranges.

As Silantyev himself writes, “For two weeks from August 15 to September 1, we, not being distracted by any duties, completely indulged in contemplation of the most charming, grandiose pictures of mountain nature, preserved in virgin purity, and during this time we waved more than a third of our entire journey through Altai, landed September 1 on the northern shore of Lake Teletskoy".

But how many dangerous adventures, difficulties, hardships, minutes of despair had to endure along the way! At times, it seemed that there was no way out, and despondency took possession of the travelers. After a many-day journey from the Rakhmanovskie keys, we reached the Karagem river, which flows into Argut.

It rained for two days, everyone got wet, the tents were leaking, piercing wind and dampness did not allow to light a fire. But most importantly, it turned out that the Russian guides did not know the further path, the Kalmyks (Altaians) encountered along the way scattered, the horses knocked down their legs and could not go any further.

What to do? The easiest way would be to get to Ongudai, where the wheeled road began, and from there to Barnaul. But then, forgiving the dream to go to the most interesting places in Altai, to see Lake Teletskoye, collect zoological material and information about local maralniks there.

And then Silantyev decided to find the Kalmyk Bosko, something like a centurion, the Altai elder, convene a council and try to find the Altai guides. So they did. They found two Altai people, and they brought Bosko. But he found himself drunk to death, and besides, none of the Altai people knew the Russian language, and travelers did not know the Altai language. However, with the greatest difficulties everything worked out, found guides, hired fresh Kalmyk horses and set off.

For five days travelers traveled with guides who did not know a word in Russian, but on the other hand, they completed the entire plan and saw the most beautiful part of Altai. Thus ended the fascinating and very necessary journey of Silantyev to Altai.

Antler-based drugs have long been valued by Chinese and Tibetan medicine and have long been denied by European doctors. Now pantocrine is a medicine recognized as a medicine that restores human vitality. Antlers gave a good income, and breeding deer became the most profitable business in Altai.

Breeders quickly grew rich, and following their example, the breeding of deer began to move east: to Khakassia and even to the Far East. Before the revolution of 1917, the number of deer in the farms of the Bukhtarminsky Territory exceeded 10 thousand heads.

The civil war and the ensuing devastation, and then violent collectivization, greatly undermined the industry. After 1995, with the transfer to private ownership, maral deer farms quickly began to recover where they were before the revolution. For example, they appeared even in the Zyryanovsky district.

In 2002, I happened to visit those deer-growing villages along Bukhtarma. In Fykalka, I was surprised not only by the picturesque surroundings, but also by the patriarchal look of the village, which, it seemed to me, retained its appearance even in the XIXth century.

A huge one and a half-story hut, towering on a hill in the center of the old village, attracted attention. The view is the most shabby, neglected. Climbed up a high staircase to the porch: on the doors of a hefty barn castle; Apparently, there is an abandoned store.

Whose house is this, it begs for itself, at least, I would like so much. But they asked local residents and it was confirmed: this is the Sharypovs house. If we lived in a civilized country, there would definitely be a museum of deer breeding and tourists would come here to get acquainted with the rich history of the region, the country of “masons”, Bukhtarminsky Belovodye. And so ... it is bitter and insulting to see how the priceless relics of history collapse. A story we could be proud of.

Now maralovodi are going through hard times. There was competition from countries where antlers had never been exported from before. This is Canada, where there are a lot of deer, as there is a good job of preserving wildlife. This is New Zealand, where deer imported from Europe multiplied so much that they became a threat to local Aborigines - very valuable animals, and especially marsupials.

They even created a special service for regulating the number of deer and their shooting. And, nevertheless, maralovodov of the Kazakhstan region has prospects, because the quality of local antlers is higher than the rest.

The key to this is the rich Altai forbs, equal to which it is difficult to find anywhere.

Authority:

Naturalist writer, photo artist, local historian Alexander Lukhtanov.