You are here

History complex of A. Yassavi.

Best sights in Turkestan 2026.

“He who conquers himself is the mightiest warrior”

Confucius.

Holy sites of Turkestan.

Fifteen centuries have swished above the lombardy poplars of Turkestan. During this time the land, grey with wormwood, has seen a lot, has lived through a lot Vth century of the Chrestian era. We try to date the foundation of the town at this time. What was it, this time like?

Let us cast a retrospestive glance at the Euroasian continent. Its geography has not undergone great changes: the same seas, rivers, mountains, deserts... But how unwonted are their names for our ear! The Black Sea - Pontus Euxinus, The Sea of Aral - the Sea of Ephthali-tes, the Volga - Ra, the Don - Tanais, the Syr Daria - Jaksart, the Amu Daria - Jeihun.

Across the continent - from the Pillars of Hercules, over the entire Mediterranean, the Near East, Central Asia and further towards" the Indus a zone of civilization stretches. The Hellenes call it Oikumene. On the other side of the Himalayas is Far Eastern Oikumene, which is called Tien Sia (Celestial) by its inhabitants. Oikumene is thickly inhabited.

Its arable lands are fertile, the towns are rich and populous. Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Bukhara, Maracanda (Samarkand), Patili-putra. The fifth century saw the earth's first-ever city of a million people. This is Changang. Great is the fame of these cities.

Nobody yet knows of the village of Lutetia - future Paris, the fishermen's settlement on the Thames - Londinium. Moscow is not yet 'under construction, «Lay of Igor's Host» is not yet written, there are over a thousand years to go before Columbus discovers the New World.

What ever do we know about the town of Turkestan or Yasy, as it was called till the XVIth century, about its settlers? Almost everything and nothing at all. Nothing, because excavations of ancient Turkestan were not made. Everything, because a study of similar settlements, as well as Chinese and Indian chronicles, provide the present-day specialist with a great number of facts, using which he can reconstruct that remote pasl with ample authenticity.

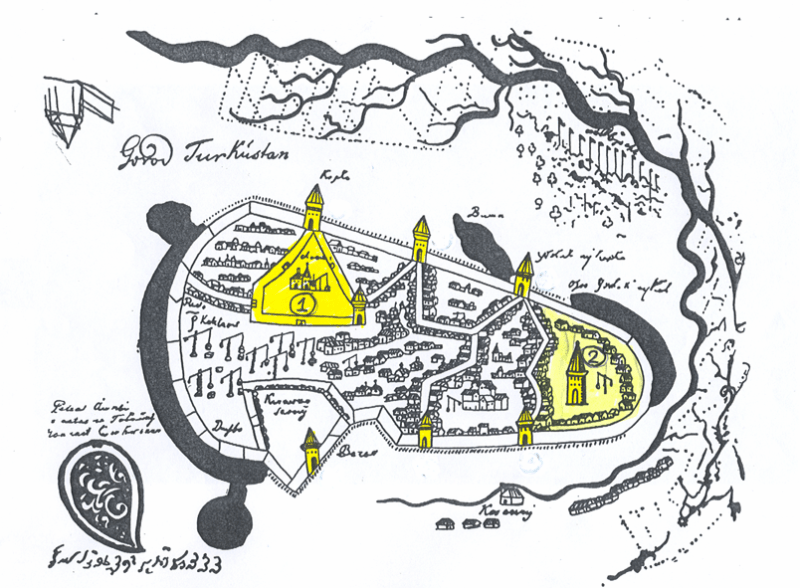

Aerial photography which, incidentally, was first used by Professor S. P. Tolstov in Central Asia reveals precise planning of ancient settlements. If we proceed from the principle of analogues, Turkestan looked thus: in the centre there was a fortified citadel with dwelling houses around it.

That all was enclosed by a wall with a gate and turrets with arrow slits. The crop areas were also enclosed by a wall or a rampart... The buildings were, as a rule, erected from flat raw bricks. Farming was the basic occupation of the community, which grew wheat, naked barley and crescent-shaped lucerne called mous.

These were old crops, new ones were rice and cotton. There were as well collateral persuits such as pottery, leather manufacture, weaving, weapon-making and jewelry which were not yet autonomous handicrafts. The community members were engaged in them only at the time free seasonal work.

In the 5th century the farming zone of the Syr Daria area grew considerably larger. Primitive smallarea farming was replaced by more perfect oasis farming. Thus, the community could till not liny plots near shallow little rivers but whole fields - up to a hundred hectares, using for irrigation the water of such a large river as Syr Daria...

The community members did not raise crops only for themselves, part of the crops went for sale and barter at markets in the towns along the Silk Road. People here lived both a labour and intensive spiritual life. The Vth century was the heyday of fresco painting. House walls were painted with whole scenes to the subject of war, everyday life, work, hunting ard recreation.

The next, VIth century radically recarved the political map of Central Asia. The Turkic tribes of the Altai, after conpuering and uniting some tribes living in the south-east, formed a new statehood-Turkic kaganate. In the 70s the Turki, having accomplished a number of campaigns to China, made her recognize their independence and pay a tribute in silk. They removed Iran from the control of considerable sectors of the Silk Road.

Their power was recognized by the emperor of Byzantium himself. As a sign of respect he sent emissaries to the Turkic kagans with rich gifts. That was the time when Turkic language peoples finally acguired their historic native land in the area of the steppe stretching from Baikal to the Volga.

The Buddhist pilgrim Suang Tsang who travelled in the 630s on the caravan path of the Silk Road has left for us interesting information about the Turki who inhabited the banks of the river Chgeng-Chgung (Pearl - modern Syr Daria).

According to him in summer they used to wear clothes of cotton fabric, wool or leather, which outlined the body. In winter they warmed themselves by clothes made of felted wool. They were tall people, some of whom were engaged in breeding animals, oihers - in trade, still others - in crop-growing. The soil was good for growing wheat and red millet. Forests were few. The people knew writing. The alphabet contained 32 letters, the lines were placed from top to bottom.

He wrote about his meeting with the kagan: «The kagan wore a green cloak, he let his hair down and, like the local settled reople, he covered his forehead with a length of silk wrapped round the head several times. As distinct from the kagan all his suite had their hair plaited.

The kagan lived in a big tent with a multitude of articles of gold. In the tent the dignitaries, wearing silken clothes, sat on felt carpets in two rows, standing behind them were the kagan's body-guards, dressed in armour. In the tent there were ambassadors from China and Gaochan (Uiguria)...»

Such was the life, as we picture it to ourselves, in the Turkic kaganate and the subordinate town in question. Yasy attained its highest flourishing in the 12th century when the fate of the town was interspersed with the fate of the sufist poet and preacher khoja Ahmed. Here he lived the greater part of his life, preached and was buried in 1166 or 1167 with great honours in a specially erected small mausoleum which then became a place of pilgrimage and worship for Moslems.

The location of the town on the ancient caravan path which was a branch of the Great Silk Road between Dasht and Kipchak and the agricultural oases of Central Asia - Khorezm, Tashkent, Bukhara and Samarkand, a good geographical position, as well as pilgrimage of believers promoted the brisk trade and development of the settlement.

Today, as a thousand and a half, a thousand, eight hundred years ago, you can hear in Turkestan the noise of the market filled witH vegetables, grapes, melons and water-melons. When you go along the trade rows, you feel the dust of centuries under your feet, the indissoluble connection of times.

The picture of the long past days appears as a delusion. Day had just broken. In the thick branches of the willow bent over the cool of the aryk the nightingale had trilled his morning song. From the high minaret of the market mosgue the muezzin had called the true believers for the first prayer.

The fire sellers had carried red-hot coals to their regular customers and presently a thick smell of bread began to float above the bazaar sguare, the orchards of shakhristan, the long caravan-serais and the crooked and narrow streets of the rabad killing all other smells. It came from the flat cakes being baked in tandyrs - earthen ovens with spherical vaults.

But, alas, fresh bread is not so easy of access as its smell. The poor man*s breakfast more often that not consists of a handful of boiled wild beans-masha slightly seasoned with sesame oil, a piece of kurt and some mouthfuls of iran.

But the askhana-bazaar - the bazaar of eatables - appears in all its splendour before the one who can pay. Next to ihe pile of fresh, steaming flat cakes are rosy, justcooked pyramids of samsa - meat and roasted onions in dough.

Tea pots are steaming on round clay trays - dastarkhans - decorated by an intricate ornament. Nearby beshbarmak and pilau are being cooked in bronze cauldrons of different size. The kurjoums are filled so much that it seems they will split any moment. They contain drinks to any taste - shoubat, koumiss, iran, katyk.

To any taste is haeva - of sesame, nuts, peanuts infused in soap-root water, grape juice, honey, mutton fat with almonds. The izyum-bazaar is full of dry and fresh fruits. The shala-bazaar is set with sacks of while and pink rice, red winter wheat, naked barley, sorghum and amber-coloured millet. Such a variety of cereals in not available at present.

Only archaeologists find them along with remains of hessian, skilfully woven from fibres resembling Central Asian sedge and basi of the tugai poplar - turanga, when unearthing dwellings. The crooked and narrow streets of the town, leading to the trading centre, get filled with many-coloured clothes.

Above the motley crowd there is heaving of turbans, fezzes, embroidered skull-caps, hats, telpeks, papakhas, malakhais, caps, li seems that people from all over the world come to these streets to fill the market sguare.

This is repeated every morning, day by day, for months, years, centuries. Every morning the mukhtasib - the market overseer - appears at the bazaar. He controls the precision of. weights and measures, the fulfilment by the shop Craftsmen of the production rules, tells the newly arrived merchants the local prices of goods. And the haggling begins.

What on earth attracted people to the Great Market? What goods could one buy and sell at it? One of the active participants in the international trade, especially in the pre-mongol period, was Russ. At the foreign market it sold furs of lynx, sable, polar fox, polar bear, beaver, desman, squirrel, marten and ermine.

Apart from furs Russ sent to the caravan markets all sorts of linen fabrics, as well as falcons and gyrfalcons trained for hunting, amber to .be burnt for aroma in Buddhist temples, mammoth tusks. Besides Russian merchants brought for sale rye, barley, honey, decorated utensils and toys of wood, neilloed silver, chain armours, forged copper, birch bark quivers with arrows, metal shields.

After having all their goods sold oui, they look home taffeta, the fines! cashmere, muslin and oiher «Indian veils», variegated Persian carpels, whalebones, medicinal ginseng roots, liquorices, wormseed, tea, rice, ambergris and many other strange things. They also took away quite a lot of semi-precious stones in their caskets.

Turkestan had very wide business contacts. There was hardly a country which did not send its caravans here. What did they bring? The brightest silks were brought from Hindu Kush. .Porcelain was brought from China.

Only the country beyond the Great Wall knew the secret of its production, nobody else at the time knew the mystery of turning clay into dazzlingly white bowls and vases with clearly defined, fine designs on them. As a matter of fact there were many mysterious and mystical things, about the Chinese trade. All sorts of drugs for diseases and cosmetic balms prepared on special recipes, which healers kept secret, evoked a particular interest.

Few Persian goods reached Turkestan. The Arab sources mention only ozocerite or mineral wax .which was used to light up dwellings and to prepare medicines and aromatic pations, basma, skins of the Asian tiger, and jewellery stones. That must be all.

Byzantium brought axamites woven in six threads, many-coloured velvets used to make the most expensive garments, damask with patterns and watered forms, silver and gold woven brocade of Greek make. But the prevailing fabric at the market was red white and green corton zenden. The local masters were so good at making it that dignitaries and tsars purchased it at the cost of brocade and had clothes made for themselves.

People of more modest income were content with cotton fabrics - calico and coarse cotton cloth. No matter the state of the market changed, no matter how heavy the load of the caravan, going to Russ, the land of the Varangians, Germans or Franks, might be, there always was room in the bales for astrakhans - a peerlees treasure of the nomadic Turki. We have a good idea about what the masters themselves traded in at such bazaars as in Turkestan.

For sale they offered «sheep skins processed so that they looked like satin», morocco pillows, saddles covered with durable kulan leather, harness with silver embossing, leather quivers, bows inlaid with jewelry, arrows, grain, filigree, household objects of metal and wood, stained Turkic glass (which, incidentally, the Turki taught the Chinese to produce), blankets from taffeta lined with fox and ermine furs, fine silk, cotton seeds, linen fabrics, pigs of ferrous and non-ferrous metals.

Turkestan stood on the boundary of agricultural and nomadic tribes. Therefore they drove together plenty of animals here. We can judge of the scales of trade by the words of a mediaeval author who noted that in Sygnak, which stood in the pre-mongol period on the lower Syr Daria, they sold over five hundred camels every day. We know some prices of goods of that time.

The lynx skin, for example, was an equivalent of five rams, a well dried antler of the marai was paid for as mich as it weighed. At the time when the poor dervish and versifier Khoja Ahmed used to roam about the bazaars of Turkestan the town was motley and populous. The poet's verses were only coming into ixistence to acquire immortality.

There are many legends spread about Ahmed Yasavi. From one of them we learn that at the age of 63 he settled down in an underground cell and spent the rest of his life there as a token of mourning for the prophet Mohammed who died at this age and whom the poet considered his teacher. Not only his family but the numerous disciples, who listened to the exhortations and edifications of the sheikh, lived near the cave.

Every period of time has its own vision of people of the past ages. For us Ahmed Yasavi is first of all a poet whose verses have gone down in the world teasury of human culture. What do we know about him for certain?

Let us open the Great Soviet Encyclopedia: «Ahmed Vasavi (about 1105 - 1166), Central Asian sufic poet and advocaie. Wrote in Chagatai (Ceniral Asian Turkic language). Author of collection of mystical verses «Khikmet» (published in 1878). The collection is valued for folk forms of verses in it.

The language of verses also contains elements of Oguz dialects. Akhmed Yasavi*s popularity was great. Starting from 19th century his verses were published in Kazan and Tashkent». Akhmed Yasavi was born in the town of Sairam. His parents' occuration is unknown. The people's memory has only retained their names. The father - Ibragim, the mother - Karashash.

Akhmed's first preceptor and educator was sheikn Arslan-Bab. After his death the youth moved to Bukhara and had a difficult course of sufic teaching with the celebrated khoja Yusuf Khamadani and was given the right to explain «the ways of cognizing truth».

Dervishes of this order professed absolute asceticism, renounced the earthly blessings, wore coarse woollen cloaks called sufies. They believed they were destined to serve «true faith» - tarikat which as regards its ideological orientation was close to popular ideas aboul the just structure of the world.

Nizami, Navoi and Khaizf considered themselves sufists. Akhmed Yasavi. justly ranks with these great heralds of the ideas of Humanism. His verses from «Khikmet» (Wisdom) are still read and appreciated not only by the Turkic language peoples.

They are our asset, as well as the mausoleum erected above his burial-vault which has become an architectural pearl of the mediaeval Orient. The mausoleum over Akhmed Vasavi's tomb was erected 233 years after his death at the order of Tamerlane.

We ought to do justice to the state wisdom of Timur Lenk. By doing so he derived some benefits. The tomb of Akhmed Yasavi had long been a place of pilgrimage, and a three-time visit to it was equal to a trip to Mecca. The construction of this magnificent mausoleum was, of course, to increase the influx of pilgrims to Yasavi's tomb and, hence, to increase the inflow of money into the treasury of the Baghdad caliph. In Islamic preachers Timur also acquired devoted allies as some of the income went their way, too.

And lastly, as the protector of the saints' graves he rose in the opinion of people, especially in the eyes of the steppe dwellers, while the building was to immortalize his name. We do say now: the museum was built by Timur.

Palaces and shrines were constructed at the order of rulers. However, they were built by people. And the Akhmed Yasavi Mausoleum is first of all a material embodiment of the people's genius, a monument to its rt.

Different sources indicate that Timur personally took pan in the basic dimensions of the dome: diameter - 41 gyaz, circumference - 130 working out of the plan of the future structure, determined the gyaz (1 gyaz - 0,44 m). This may be true. But history has retained three more names.

These are Ubaidulla Sadr, Khoji Khasan and Shems Abd-al-Bakhab. Along with thousands upon thousands of the unknown builders they can be rightfully considered true creators of the monument, whose domes still compete with the blue sky.

For the construction of the mausoleum walls they used baked bricks. The technological purity of brick making was brought to perfection. There is not a single rootlet of plant, not a single drop of humus in the bricks. Sulphate and magnesium salts were removed by repeated flushing of the clay mix.

The uniformity of clay baking was achieved by means of thorough roasting. As a result the bricks were smooth and resonant like a mountain brook. It took scientists much time to find the place where clay for the mausoleum had been taken from. Now the place is known.

This is the Sauran natural boundary, 35 km off Turkestan, near the ruins of the old fortress. For glazes they took sand and clay of the now restored Kotyrbulak and Tuetas quarries. True, the renowned orientalist M. E. Masson wrote in his time: «According to a legend the bricks and ceramic tiles for the burial vault were made in Sauran and handed from there by a file of standing people to Yasy for building.

But the scientist referred to a legend. A chemical analysis of numerous quarries round Turkestan confirmed its auiheniicity. Using Sauran clay, the pestorers managed to obtain bricks and ceramic tiles identical to the original.

This greatly improved the quality of present-day work on the mausoleum, helped to renew the old technology of making bricks, glaze and ceramics. The Turkestan Restoration Shop has mastered their production.

As regards the scale the Khoja Akhmed Yasavi Mausoleum is equal to the Bibi-Khanum Mosque in Samarkand, the Ak-Serai Palace and the Dorussadat burial-vault in Shakhrisyabz. The masoleum is a restangular building of 46,5 by 65,6 metres.

The walls are 3,1.8 and 2 metres thick. The foundation is of rubblestone laid at the depth of up to 3 metres. This all holds the main part of the construe lion - the dome of 18.2 metres in diameter. As a matter of fact, it was the dome that determined all the other elements of the structure.

The building of the mausoleum is in the first place an engineering siructure made to stand long. Durability (the mausoleum is nearly six centuries old) does credit to the engineering mastery of its creators. We say: to build for centuries. But this expression is often perceived as a meiaphor. However, here it is perceived in the literal sense of the word.

During the centuries the mausoleum withstood quite a few earthquakes, hundreds of thousands of limes its walls were made burning hot by the sun and cooled by cold, they fired guns at the mausoleum, more than once it fell into the state of neglect. That all was a serious examination for the design and the material of which it was made.

The building has an appearance of one whole, but in fact in is divided into eight independent blocks. In it lies the secret of the seismic stability of the building, though it is 37.5 metres high, which is not little even by the present standards.

The main hall of the mausoleum is called kazandyk. In the centre there is a bronze rilual cauldron - kazan. For the Turki a kazan was a symbol of harmony and hospitality. Therefore a special attention was given to its dimensions and outward appearance.

The Turkestan kazan in this respect has no match. It is 2.45 metres in diameter and 2 tonnes in weight. The casting alone needed great mastery. But the metallurgists solved this complicated problem both technologically and aesthetically.

Subtly feeling the form and metal, they embellished the kazan with three belts of raised Arabic inscriptions against a floral ornament. The ten sheer handles were given the form of lotus flowers. This wonder was created by Abdulgaziz Sharafutdin-uly AI Tabrizi.

We could detail the story of the mausoleum as an architectural monument, but there are quite a few works written about it by specialists. Our task is to introduce the town of Turkestan, one of the oldest in the land of Kazakhstan. It has its own appearance, its own destiny.

Emerging from the roots of the fast-flowing time, as it were, it nevertheless remains modern, where living modernity stands out as distinctly as living antiquity.

Authority:

Book “Turkestan” R. Nasyrov, Oner Almaty, 1993

Photos by

from the Turkestan album. Published in 1872 in St. Petersburg, by order of the first Tashkent governor-general, Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman. The album included four parts: archaeological (two volumes), ethnographic (two volumes), crafts of the peoples of Central Asia (trade) and historical part. The number of photographs is more than 1200. Compiled by A. L. Kuhn (1871 - 1872). For more than two years, the collection of materials for a multivolume publication was carried out in the military-topographic department of Tashkent, where lithographic parts of each plate were printed. The complete set of all volumes and parts of this book is kept today in only three collections: in the National Library of Uzbekistan in Tashkent, in the State Library named after V. Lenin in Moscow and in the US Library of Congress in Washington. Each of the six volumes of the Turkestan Album is a huge folio, upholstered in green leather, measuring 45 by 60 centimeters. Each page of the publication contains from one to eight photographs made using albumin printing technology (based on egg white). In 2007, the US National Library of Congress completed a complete digitization of all pages of the Turkestan Album.