You are here

History of mosque of Bibi Khanum.

Trip to Bibi Khanum mosque.

“...it seemed a part of her life, to step from the ancient to the modern, back and forth. She felt rather sorry for those who knew only one and not the other. It was better, she thought, to be able to select from the whole menu of human achievements than to be bound within one narrow range”

Orson Scott Card.

Walk on Bibi Khanum mosque.

In fact, Bibi-hanym was the oldest wife of Amir Temur, Chinggisid princess Sarai Mulk-Khanym. She was a daughter of Chagataid khan Kazan (1343-1346) from the clan of Nikuderi, controlling over huge areas of southeastern Khurasan, Kerman, in the XIII – XIV centuries.

In the 30s - 40s, the Nikuderi managed to take a throne of Chagatai khans. First, Sarai Mulk-Khanym was married Emir Hussein (1364-1370), the grandson of emir Kazagan (1346-1358), who dethroned her father. In the period before Amir Temur, Emir Hussein was a supreme emir of the Chagataids.

His residence was Kabul and later in Balkh. In 1370, Amir Temur achieved dethronement of Hussein and was declared as a supreme governor of Chagatai ulus. Hussein was killed, and Sarai Mulk-Khanum became a wife of Amir Temur. During all period of Amir Temur reigning, she enjoyed exclusive respect in the family of the Temurids.

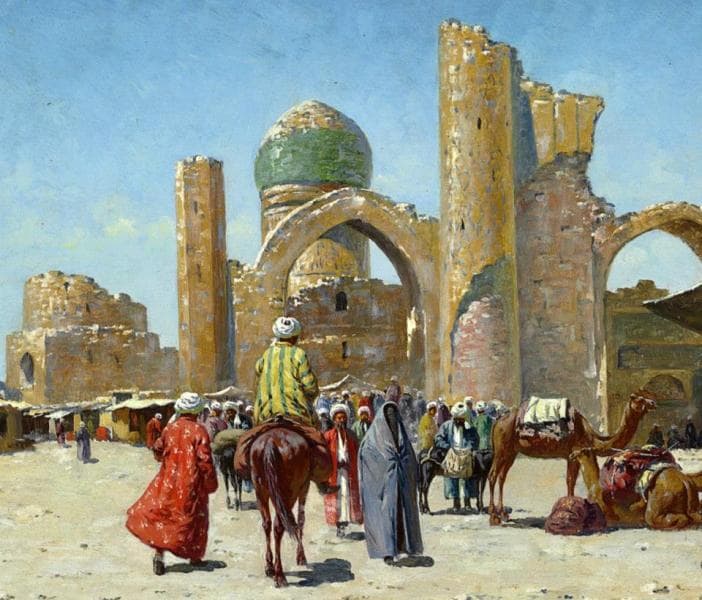

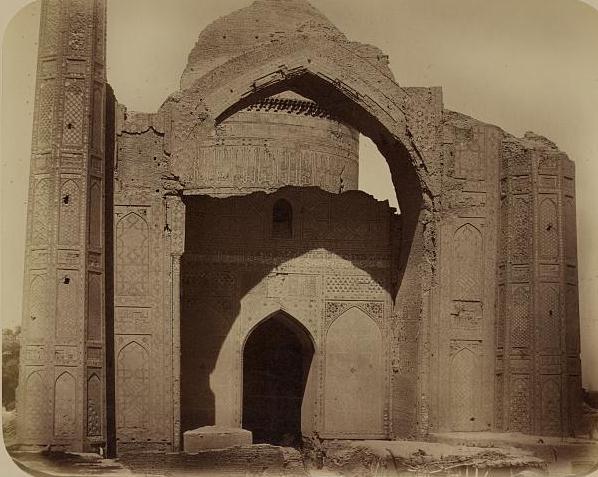

As it neared completion, Ruy Gonzalez de Claviho witnessed the infirm emperor throwing coins and meat to the workmen from his litter to goad them on, 'as one should cast bones to dogs in а pit'. An observer wrote of the finished mosque: “Its dome would have been unique had it not been for the heavens, and unique would have been its portal had it not been for the Мilky Way.”'

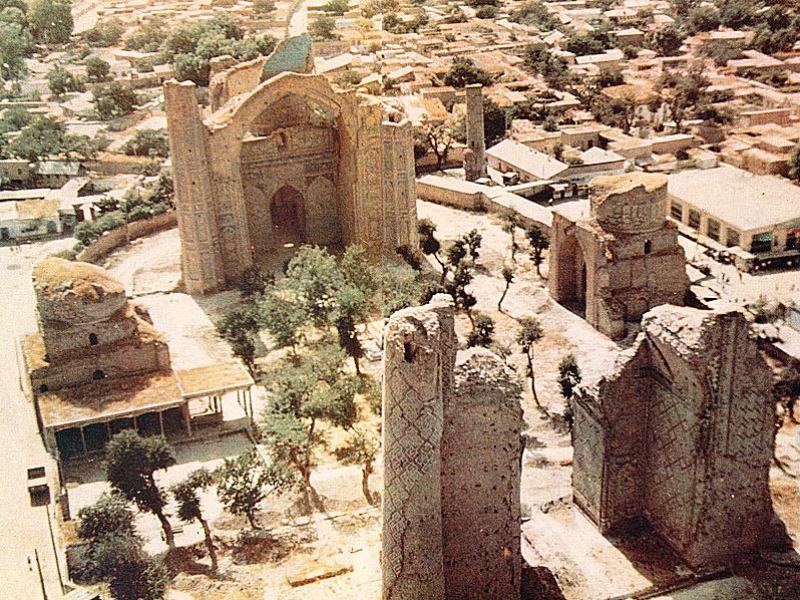

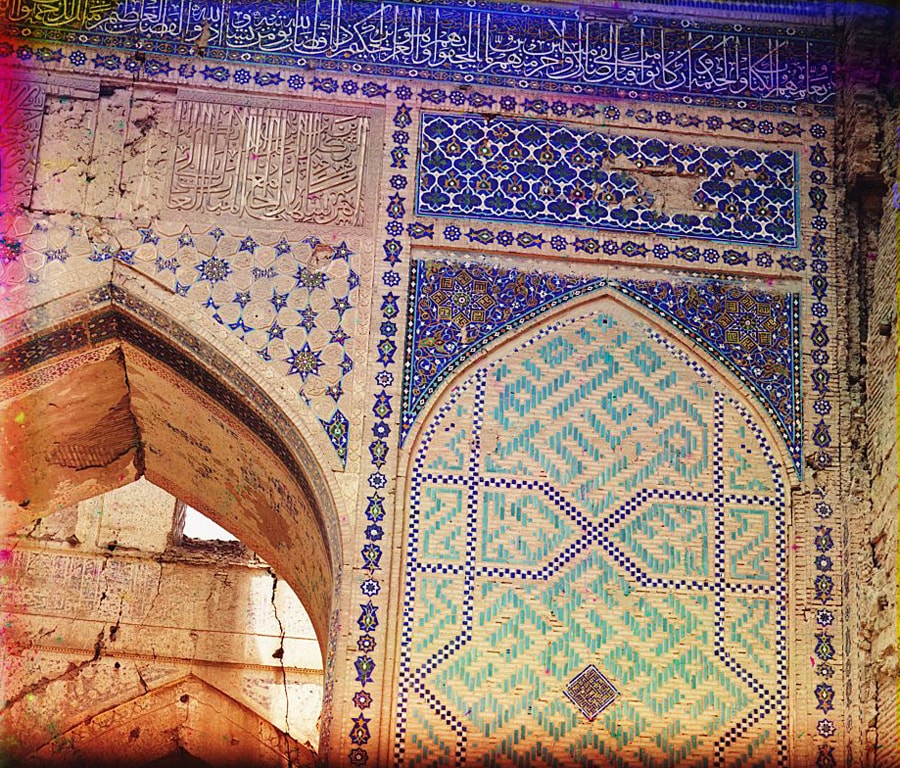

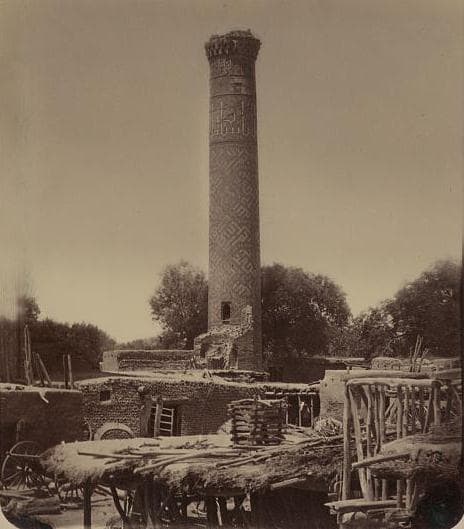

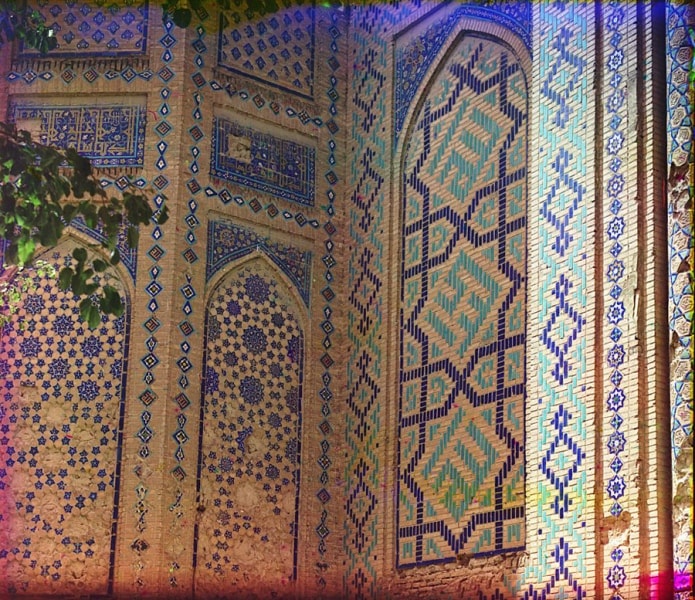

The portal was nearly 30 m high and the dome even higher. Decorated with majolica mosaics, carved marble and painted and gilded papier mache, they stood at the west end of а marble-paved, colonnaded courtyard larger than а football pitch (130 m by 102 m), with а minaret at each corner.

The main gates opposite the mosque were made of seven different metals and were flanked by ceramic columns 50 m high. Two minor mosques looked inward from the north and south towards а giant marble Koran-holder in which rested the Osman Koran, said to be the second Koran in history, whose script was so big the imams could read it from balconies along the colonnade.

The Koran-holder is still there and crawling under it is said to make barren women fertile. The Koran itself was brought to Samarkand from Damascus by Tamerlane, and sent to the Hermitage in St Petersburg by General Kaufmann in 1875 and to the Uzbek Academy of Sciences in Tashkent in 1919.

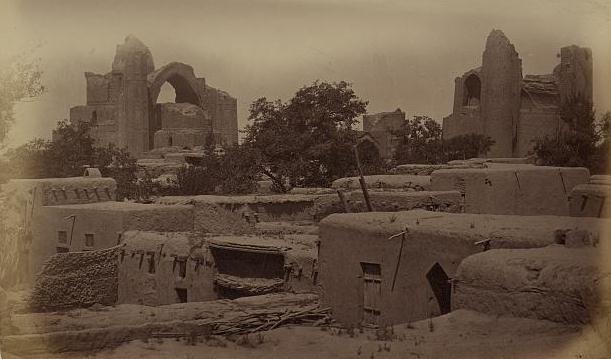

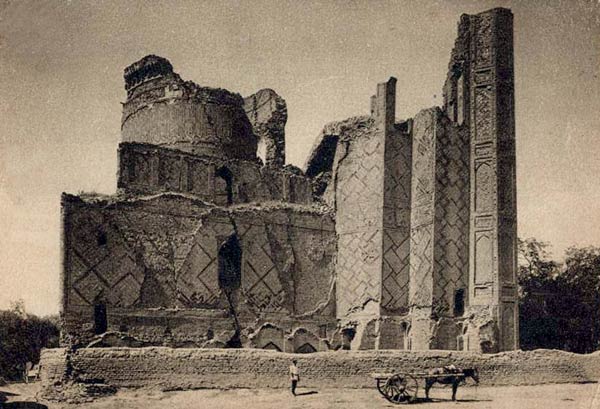

The Muslim authorities in Tashkent finally recovered it in 1989. The Bibi Khanym complex had been completed in an almighty rush and started crumbling even before Tamerlane's death the following year. А XVII century earthquake destroyed more than half of it and another in 1897 left cracks in the main dome, already hit by а Russian shell in 1868.

Lay-people had stopped praying here for fear of falling masonry. Now the clergy left too, and the courtyard became а cotton market. The walls had long served as а brick quarry for other building projects and the great gates had bееn melted down by an avaricious emir of Bukhara.

Original plans for the site were discovered in Leningrad in 1974, and five years later reconstruction began. Much brickwork has been strengthened and the courtyard walls and minor domes have been re-build, but the money has run out and the main mosque's scaffolding and crane аге now permanent features of the Samarkand skyline.

There is а chance of funds from UNESCO, but not if the mosque is closed to non-Muslims as some local Muslims want. Despite everything, enough remains of Bibi Khanym to imagine its former scale and spleen dour, and somehow the rusty building apparatus lends the place а gritty realism the Registan lacks.

The queen herself, attended by up to 300 ladies-in-waiting when alive, may be buried across street Tashkent under the brown-domed Bibi Кhаnym mausoleum, as yet unrestored and closed to the public. Nothing remains of а madrasa to which it was attached nor of the nearby city gates which stood at the bottom of street Tashkent where the 'Golden Road' entered Samarkand from Tashkent.

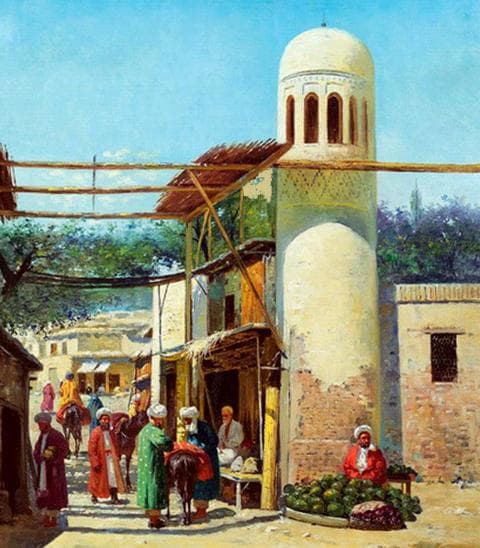

But the bazaar, pressed up against the east wall of the Bibi Khanym complex, is alive, teeming and unbothered as ever by western talk of 'free' and other sorts of markets. It is still called the local bazaar, but collectivization never really affected what was sold here or bу whom or how much for.

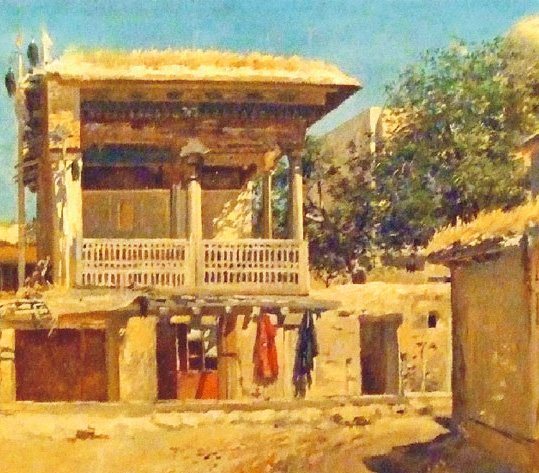

Chinese goods аге making а comeback after 400 years, but more in the line of tracksuit tops than silk and lacquer-ware. Opposite the bazaar, on an ancient site in the corner of Afrasiab, the Кhazrat Кyz mosque (1850) is unusual for its separate asymmetrical portico.

The elaborate designs on the mosque's wooden ceiling аге being repainted with а Swiss grant.

Authority:

Alexey Arapov. “Samarkand. Masterpieces of Central Asia”. Tashkent, Sanat. 2004.

Photos by:

S. Prokudin Gorskiy.