You are here

Przhevalsky's horse in Altyn-Emel park.

Wildlife Tours to Altyn-Emel park.

"Where the horse is, there is no evil spirits"

Kazakh proverb.

Photo tours in Aktau mountains Altyn-Emel park.

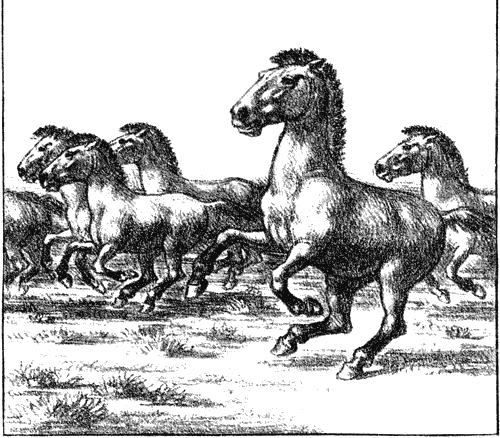

The newfound horse, called the Kirghiz kertag, and also the Mongols [tahi], lives only in the wildest parts of the Dzungar desert. Here the kertags are kept in small (5–15 specimens) herds grazing under the supervision of an experienced old stallion.

Probably, such herds consist solely of females belonging to the leading male. With safety, these animals are said to be playful. Kertags are generally extremely careful; besides gifted with excellent sense of smell, hearing and vision.

They are quite rare; and besides, as mentioned above, they stay in the wildest parts of the desert, from where they visit watering places. However, the described animals, like other animals of the desert, are likely to remain without water for a long time, being content with juicy saline plants.

“I personally,” he writes, “managed to meet only two herds of wild horses. One of them could sneak up on a well-aimed shot, but the animals sensed my friend in the wind, at least a mile away, and set off to leave.

The stallion ran ahead, protruding its tail and arched its neck, generally with a landing completely horse-like; seven probably followed females. At times, the animals stopped, crowded, looked in my direction and sometimes kicked with each other; then again trotted and finally hid in the desert”.

The hunt for them presents the greatest difficulties, since it can only be ventured in the winter, when the desert is covered with snow and the hunter does not risk dying of thirst; then kertags are so rare that you sometimes have to travel hundreds of miles before you come across them.

Therefore, it is necessary to stock up on a warm yurt and food for a small caravan of hunters. N. Przhevalsky managed to meet only two herds, but could not shoot; the copy delivered to him by the Academy of Sciences was killed by Kyrgyz hunters in the sands of southern Zhungaria and presented to him by the former head of the Zaysan port, Tikhonov.

With the exception of Zhungaria, kertag is not found anywhere else. A little later Przhevalsky, on his new trips to Central Asia, passed through the deserts of Dzungaria, and there he saw with his own eyes the elusive zerlik hell.

Przhevalsky never managed to get close to a single wild horse, “but still got his skull and skin.” They were presented to him by A.K. Tikhanov, the head of the Zeissan post (close to the Russian-Chinese border of the village where Przhevalsky completed his second Central Asian journey). And the skin came to Tikhanov from the Kyrgyz hunters who hunted in Central Dzungaria.

Then, at least, you cannot die of thirst. But at this time, the hunters will be harassed by severe frosts day after day. To hide from them at least at night, you need to take a felt yurt with you; then you should stock up on food and generally equip a small caravan, since on such a hunt you will have to travel many hundreds of miles and spend a month of time.

I personally managed to meet only two herds of wild horses. One of these herds could be sneaked up on a well-aimed shot, but the animals sensed my friend in the wind, at least a mile away, and set off to leave.

The stallion ran ahead, protruding its tail and arching its neck, generally with a completely equine fit; seven probably followed females. At times, the animals stopped, crowded, looked in my direction and sometimes kicked with each other; then again trotted and finally hid in the desert.

It is remarkable that in the aforementioned herd two specimens were some piebald - it was impossible to consider it well. With the exception of Dzungaria kertag is not found anywhere else. Thus, the former vast, as paleontological studies show, the area of wild horse distribution in Europe and Asia is now limited to only a small corner of the Central Asian desert.

In other parts of it there are no wild horses. I can now affirm this positively. The stories of the Mongols, which I heard in Alashan during the first (1870 - 1873 years) journey in Central Asia, about herds of wild horses on Lobnor, turned out to be fiction.

Authority:

N.M. Przewalski. “The second trip to Tibet. March 1879."

There are about two thousand individuals in the world, and this entire population comes from several animals captured at the beginning of the XXth century in Dzungaria. The descendants of those horses have been bred in captivity for many generations in zoos and nature reserves in the world.

The Przewalski’s horse book is kept at the Prague Zoo. In the USSR, a large number of Przhevalsky horses was kept in Askania-Nova (Ukraine). Before the revolution, it was the owner of Askania-Nova F.E. Falz-Fein who was the organizer of the expeditions to catch Przhevalsky's horses in Dzungaria.

The extremely limited initial gene pool of modern Przhevalsky horses creates serious problems in their breeding: the inevitable at the same time constant closely related crosses affect the viability of horses and the ability to reproduce.

Not in the best way horses are kept in captivity: in nature, wild horses were in constant motion, walking many kilometers during the day. Since 1992, the Przewalski horses reintroduction (returning to the wild) programs have been launched in Mongolia (Hustain-Nuruu National Park and the center of Takhin-Tal, the Great Gobi Biosphere Reserve, site B).

Since 2005, a third reintroduction center, Homin Tal, has appeared in Mongolia (located in the buffer zone of Har Us National Park, western Mongolia). These three wild-growing populations totaled about four hundred individuals at the end of 2015. T

here are also two reintroduction projects in China, a project in Kazakhstan and, since 2015, in Russia, in the Orenburg Nature Reserve. In the early 1990s, several horses were released as an experiment into the Ukrainian exclusion zone of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, where they began to breed actively.

Now there are about a hundred individuals, 3 herds. Previously, these wild horses were widespread in the forest-steppes, steppes and semi-deserts of Europe, the steppes and partly the forest-steppes of Kazakhstan and the south of Western Siberia to the east to the Baraba and Ltai steppes, the Salair ridge and Lake Zaysan, in addition, there was a habitat in Transbaikalia.

During the cold winters, Przhevalsky’s horses developed a rather interesting way of heating: the horses lined up in a circle, drove the foals and the sick in the middle and heated them with their breath. They defended themselves in much the same way from annoying flies: standing in a circle, their heads forward, they began to twist their tails intensely and drive insects away.

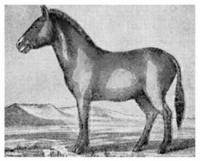

The body length of Przewalski’s horse reaches 200 cm, at the withers an average of 130 cm. Weight reaches 300-350 kg. Przhevalsky’s horse has a large and massive head, on the sides of which there are large dark eyes, providing a good overview.

The ears are very sensitive and mobile, making Przewalski’s horse a wonderful ear. Wide nostrils give a wonderful sense of smell. The mane is short black and stiff, bangs missing. Croup is not very massive. Chest and ozadok wider.

The horse's legs are short, but sturdy and strong. Color suit. A dark belt stretches along the back. Przewalski’s horses lead a herd life. They form small herds of several mares and foals; At the head of the herd is a strong adult stallion.

The leader’s power is absolute: only he chooses places for watering or feeding, the direction of the path, etc. There are also “bachelor groups” consisting of young stallions. Horses graze most of the day, but prefer evening twilight or morning.

In the afternoon, they rest, trying to choose a place on a hill for a better overview of the surroundings, since representatives of this species are distinguished by good eyesight, smell and hearing. During the rest, the mares usually doze while standing, and the stallion looks around the area to notice a possible danger as early as possible and to warn the others with an alarm.

During sleep, horses gather in a circle with their heads inward; foals are placed inside the circle for their safety. If the predator tries to attack the herd, then he will be met by strong blows of the hind hooves.

Authority:

Vikipedia.