You are here

Letter from town of Verny Semenov-Tian-Shansky. 1856.

Excursion to Semirechensk Alatau.

“On August 11, having spent the night at the Aksuy picket and having traveled another stage (23 miles) to the Karasuy picket, I began to climb the mountain to the high spur of the Semirechensk Alatau. This entire pass, known at that time under the name of Gasfortov (since it was built by the governor-general himself), was located between the Karasuyskaya and Arasanskaya stations, located twenty-seven miles apart”

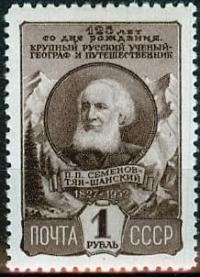

Pyotr Semenov Tyan-Shansky.

Almaty, or the Vernoye fortification, September 18, 1856.

Educational nature excursions in mountains of Semirechensk Alatau

Having neither the time nor the opportunity to compile any kind of report on the results of my travels and activities on behalf of the Society, I hasten to at least inform you, albeit in a short letter, where I have been and what I have done during the current summer, asking you to convey to the Society and Mr. Vice-Chairman from my letter everything that you find sufficiently interesting.

Upon my arrival in Siberia, two countries, far removed from each other, were bound to attract my attention, both because of their special importance and because both of them were to be included directly in the next two volumes of my translation of Ritter's "Asia".

These are precisely the Altai district itself and the southeastern part of our Kirghiz steppe, between Balkhash, Alatau and Issyk-Kul: of these, the latter will be included in the second, and the first - in the third volume of "Asia". In Altai, I was most attracted by its highest mountain group, Belukha and the Katun Pillars, as being especially interesting for observations in terms of physical geography, and in the southeastern corner of the Kirghiz steppe - the Trans-Ili region, and especially Lake Issyk-Kul, which has not yet been touched by any scientific research and is known only from inquiries, therefore my most ardent desire was during the current summer to either climb Belukha or reach Issyk-Kul. Both enterprises were associated with such difficulties and obstacles that I, of course, had little hope of successfully completing one or the other.

Already during my passage through Omsk, according to the information I had collected, I mentally almost abandoned the second enterprise, considering it completely impracticable, and I was left to try to carry out only the first. I arrived in Barnaul in the second half of June and only towards the end of that month, with the most obligatory assistance of the chief of the mining district, was I able to reach the Altai itself in Zmeinogorsk, in complete readiness for the difficult journey to the Katunsky Pillars, which was to take up the entire short summer season in the Altai, until the first cold weather and snow in the mountains, i.e., the beginning of August.

I intended to use the rest of the autumn for travel in the warmer Kirghiz steppes. But an unexpected illness, which kept me in Zmeinogorsk for three weeks, changed my entire plan. After my recovery, I was able to continue my journey only from July 20, having used the time of my illness for preparatory study of the materials for geography of the Altai, available in the mining department.

It was already too late to go to Belukha at the end of July; moreover, I could not achieve the main goal that called me there - to determine the height of the highest point of the Altai, as well as the height of the snow line and glaciers, because my barometer was broken.

Therefore, I limited myself to only a survey of the entire western outskirts of the Altai, visiting the Ulbinskaya and Ubinskaya valleys and the most important mines and climbing one of the highest peaks of the Ulbinsky group - Ivanovsky, near Riddersk.

Then, on August 1, wishing to take advantage of the still beautiful autumn, longer in the south, I hurried through Semipalatinsk to the Kirghiz steppe, opened to me by the enlightened assistance and instructions of the Governor-General of Western Siberia.

I drove slowly through the entire vast and interesting country from Semipalatinsk to the Kopal fortification, stopping wherever the interests of geography required it. In two places I managed to climb the tops of high mountains, close to the limits of eternal snow and already covered with eternal snow patches; namely, in the Karatau chain near Kopal itself and in the Alamak chain far beyond Kopal, near the Koksu River, beyond which the scientific research of our last learned travelers, A. Shrenk and Vlangali, hardly extended.

Continuing my journey beyond Koksu, I crossed the Ili and arrived at the end of August in the Trans-Ili region, in the fortification of Vernoye, or the city of Almaty, as the natives call it, - consequently, in the most remote Russian settlement in Central Asia.

Town of Almaty lies at approximately the same latitude as Pisa and Florence, at the headwaters of the Keskelen River system (on the Almatinka River), at the foot of the majestic range of giants of the snowy Kungi-Tau ridge, which borders Lake Issyk-Kul on the northern side.

After 300 miles of travel from Kopal through desert mountains and wide sandy steppes, my arrival in Almaty on the evening of August 27th made a magical impression on me. That evening, this remote corner of Russia was seething with life. The long, beautiful, newly built wooden barracks were brightly lit with joyful lights in every window.

rode out onto a vast square, where brightly burning rows of bowls and small lamps outlined the frames of the still unfinished buildings, which seemed to be completely finished, beautiful houses. The square was full of Russian people; the illuminated monogram of the Emperor occupied its center.

Military music and round dance songs enlivened the scene. The rapidly developing city of Almaty celebrated the day of the coronation of its Emperor on the remote and most obscure border of Russia with the same lively patriotic joy with which it is celebrated in the heart of Russia, in its capital city.

And all this took place under the cloudless sky of the naturally blessed south, in the middle of a warm midday night, refreshed only by a light wind, carrying from the mountain gorges through the atmosphere the aroma of ripe wild apples, to which the city of Almaty owes its name.

The Kungi-Tau range, stretching from east to west approximately in parallel with the Caucasus (Elbrus, i.e. at 43° latitude), between Keskelen and Turgen, another significant, more eastern tributary of the Ili, goes far beyond the boundaries of eternal snow and in its height, of course, surpasses all the more northern Asian snow ranges, i.e. Alatau, Tarbagatai and Altai.

The three-headed giant Talgarnyn-Tau, placed right in the middle of the entire range, in the upper reaches of the Talgar, also a tributary of the Ili, is picturesquely dressed in a dazzling mantle of eternal snow and hardly even in its absolute height does not compete with Mont Blanc.

The entire ridge of mountains between Keskelen and Turgen is so high that in this interval there is not a single convenient mountain pass that would lead from Almaty to Lake Issyk-Kul, which is no more than 60 versts from the city in a straight line.

But on both flanks the Kungi-Tau ridge drops significantly: in the west behind Keskelen, in the east behind Turgen, and it is there that more or less convenient mountain passes and routes leading to Lake Issyk-Kul have been found. Only for this reason the distance from Almaty to Issyk-Kul by the western road is already 180 versts, and by the eastern road about 250.

I had to try to reach Issyk-Kul only by these routes, to which I met in Almaty the most enlightened and obligatory assistance from the local authorities, especially from the commander of the Cossack brigade and the bailiff of the Great Horde. On the western side of the lake roams the still hostile to us Sarabagish, or Urman, tribe of wild-stone, or black Kirghiz, and on the eastern side - the Begu tribe of the same Kirghiz, who are Russian subjects.

Therefore the choice of road was unnecessary. Only Begu, in a bloody feud with the Sara-Bagish, migrated from the eastern shore of Issyk-Kul, which by the middle of the current summer remained deserted and visited only by the Baranta, i.e. bandit gangs of Urmans, attacking our subject tribes of the Begu of the Wild Stone and Atban of the Great Horde.

I decided, however, with a light escort of 10 Cossacks to penetrate as far as possible along the difficult road to Issyk-Kul, through the high mountain passes of Asyn-Tau and Tabulga-Su. I managed to safely cross these mountain passes through all the parallel ridges into which Kungi-Tau breaks up on its eastern flank, and along the Tub River descend to the very shores of the stormy light-blue Issyk-Kul, whose salty waves that day noisily ran up to its eastern shore. Here I determined the boiling point of water with a hypsometer, and therefore, hypsometrically, the absolute height of Issyk-Kul.

I cannot yet report the result, due to the lack of hypsometric tables. The wide valley of the Tub River and the parallel Dzhirgalak River separates Kungi-Tau from the snowy giant Mussart, which borders Lake Issyk-Kul on the southern side. If Kungi-Tau is only a lateral branch of the famous Heavenly Ridge, or T'yan-Shan, then Mussart is its direct and continuous continuation, which bears the name T'yan-Shan (Thian-Shan) in Chinese borders, in its highest group Bogdo-Ola, and in its more western, non-Chinese continuation - Mustaga, Mussart, Kirghizyn-Alatau.

I was therefore at the foot of the Tien Shan, whose peaks, clothed in a broad, eternally white mantle, seemed to me more colossal than Mont Blanc and Monterosa. I was only one day's journey (50 versts) short of the mountain pass of Zauki, or Djauki, leading to warm Kashgaria and Little Bukhara, to the Chinese cities of Turpan (Ush-Turpan) and Aksu, famous for their fruits: grapes and pomegranates.

Through this convenient, despite its colossal height, mountain pass, Russian trade can pave the way to the heart of Asia - the rich and flourishing bears could not be dangerous to us. On September 16, I returned to Almaty after a 14-day journey, having covered 500 miles, hardly getting off my horse during the day, and spending the night under the light protection of a canvas tent.

Now I will rest for two or three days and set off along the western road to the Chu River, beyond which, 6 miles away, lie the hostile Kokan fortifications of Tokmak and Pishpek. This new journey will complement my research on the plastic and geognostic structure of the Kungi-Tau ridge, in which, despite my expectations, I did not see a trace of any volcanic rocks and found the entire ridge to consist of syenite, granite, diorite and porphyry.

Upon returning from Chu, I will set off on the return journey to Semipalatinsk; but I still have a lot of work to do on the road, since I do not want to miss a single opportunity to see everything that can be interesting and important for geography, ethnography and geology of Asia, from outcrops of rocks with fossils to historical inscriptions and monuments.

Only in mid-October I hope to be in Semipalatinsk, where I must devote several days to collecting information about our trade with China.

Authority:

G. N. Gennadi. Letter from the full member of the Society P. P. Semenov about his journey in the Kirghiz steppe of the Siberian Department. Bulletin of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. Part 18. 1856

https://rus-turk.livejournal.com/697738.html