You are here

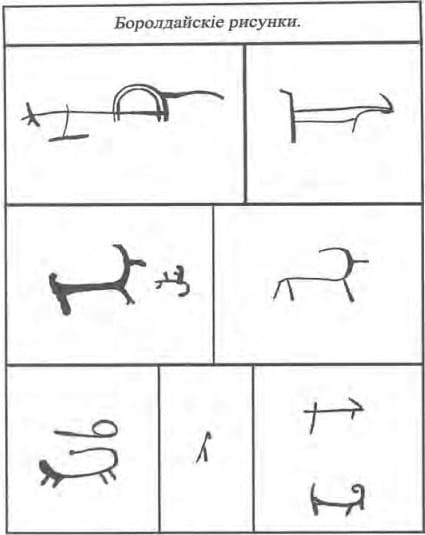

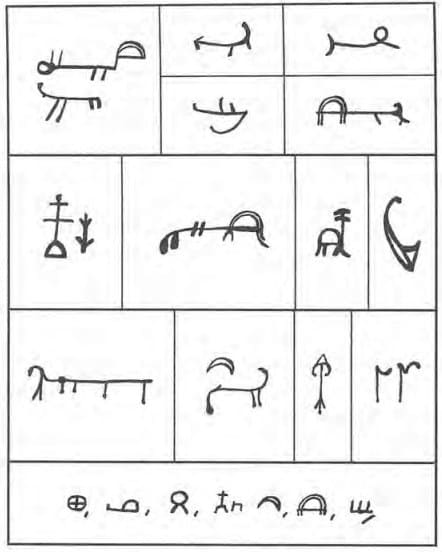

Petr Komarov on Boroldai inscriptions.

Archaeological sites of Boroldai.

"Serious study... of the region still lies ahead, and... the main role in this work should belong to local leaders."

V. V. Bartold. "On Question of Archaeological Research in Turkestan." Turkestan News. 1894, No. 7.

Trip to Boroldai petroglyphs.

In mid-August, my duties forced me to visit the Boroldai River, which flows into the Arys River on the right side, near the bridge, on the former postal route from the city of Turkestan to Chimkent. The short time I had to satisfy my hunger or thirst, I usually devoted to questioning the Kirghiz accompanying me about their customs, their work methods, and the landmarks of the places where we stopped.

Along with very interesting reports on folk customs, I also heard from the Kirghiz Molda-Temir Kulenev, who served as the elected mirab on the Chabai ditch, that somewhere in the upper reaches of the Boroldai there were inscriptions on rocks that no Kirghiz "scholar" had yet been able to discover.

Even some "Yishan scholar" they invited couldn't explain the mysterious inscriptions. According to the Kyrgyz, no Europeans had ever seen these rocks with the inscriptions, so enigmatic to the Kyrgyz. This information greatly interested me, and since I was about to travel to the upper reaches of the Boroldai River to measure the water levels in the ditches leading from Boroldai, in order to determine the low-water level of this fickle river, I invited my temporary companion, the Arys volost clerk, Fyodor Stepanovich Shpotin, to accompany me on the journey for a joint search.

We quickly ascended the Boroldai, following the left bank. I was met by mirabs, who had been duly ordered to establish the normal water levels on the tributaries and to receive from me the corresponding instructions for further assistance in determining the water level. in the river.

Along the way, the mirabs were questioned about the inscriptions we were interested in, but for some reason the Kyrgyz responded with ignorance. On August 12, we had to spend the night on the banks of the Sary-bulak ditch, which irrigates the fields of the Kyrgyz of village No. 6, Boroldai volost, Chokai clan, Orus-kar generation, along the right bank of the Boroldai River.

Here our questions resumed, but the answers were evasive. We were told only that only the Kyrgyz who had seen the inscriptions in these areas could know anything about them. However, for me, hearing the names Sadyr-Kamal, Terekty, and Ulkon-Tura was enough to keep the hope of finding something interesting in those places.

When we left our overnight camp, in the morning, the mirab of the Jar-konak ditch, Dos Toichibaev, a Kyrgyz who had accompanied me, reported to us his conversation with The Kirghiz of the village where we spent the night. According to them, their rocks with inscriptions can be seen in the area of Terekty, near Ulkon-Tura, and mysterious caves are located in the area of Baigalmak.

Soon we met a Kirghiz from village No. 6 of the Boroldai volost, of the same generation as Orus-kar, named Tuleubai Dzhanbaev, whom I immediately began questioning about the writings. This Kirghiz turned out to be knowledgeable about the area and had even seen the inscriptions on the rocks.

After some hesitation, Tuleubai decided to show them to us. His determination was also conditioned, incidentally, by the fact that a mirab from his village soon came to meet me. We didn't have to travel long. Somewhat above the mouth of the Terekty River, which flows into the Boroldai River from the left, at the top of the watershed between the left tributaries of the same Boroldai, the Kara-tasty-bulak and Kyzyl-bulak turned out to be a ridge of rocks with inscriptions and drawings on them.

The Kyrgyz attribute both to the Kalmyks. However, in my opinion, there is nothing Kalmyk about these inscriptions. On the rocks, rising in a ridge from the banks of the Boroldai River toward the Ulkon-Tura massif, are carved images of animals: horses, argali (Ovis argali), deer (Cervus tarandus or elaphus), hounds, wolves, and people.

Incidentally, saddled horses and riders with bows in hand are depicted pursuing mountain sheep, whose path is blocked by a dog. Some of the drawings are quite well executed. Besides the drawings, some symbols are carved on the rocks, some resembling Orkhon script or Kyrgyz tamgas, others reminiscent of the inscriptions on Nestorian tombstones. are presented (in photographs) in the minutes of the Turkestan Circle of Archaeology Lovers No. 2, on page 61.

The drawings are partly similar to the drawings by Saimalytas, photographs of which are given in the same publication, in the appendix to the articles by N.G. Khlodov and I.T. Poslavsky24, as well as in the work of V.V. Bartold from the stones of Naryn and Issyk-Kul.

I had only a few hours at my disposal, during which the Kyrgyz had to dam the waters of Boroldai into their irrigation ditches. Therefore, it was necessary to take precise photographs of the stones, stretching in a ridge for 100-150 A fathom, I couldn't.

F.S. Shpotin was initially fascinated by copying the inscriptions, but then, upon seeing the inscriptions, even more worthy of attention, he agreed with me that meticulously copying the inscriptions and drawings would take a very long time.

We merely agreed to devote a special trip to copying the inscriptions, slowly and diligently.

The stones belong to the Paleozoic limestone group. According to the Kyrgyz, these stones were coated with some kind of oil or fat before the inscriptions were made. I am inclined to share this opinion, as the limestone with the inscriptions stands out black, and in places where the inscriptions have crumbled, the limestone is gray.

Furthermore, some of the stones have peeled off, as if plastered, by half an inch. It seems to me that the inscription was not made by primitive people, but by a fairly cultured people who had the foresight to coat the limestone stones intended for the inscription with a special compound to ensure their durability and protect the images from rapid deterioration.

Nevertheless, time has certainly taken its toll. The stones have individual symbols on them. I tried to record only the clear symbols in the book of memories. The Terekty area is a mountain basin, enclosed on all sides, with access to the Boroldai River.

It is watered by the Terekty River, which flows into the Boroldai River from the left and, in turn, receives the Sadyr-Kamal-bulak tributary from the right, and the Irgayly-bulak from the left. The first spring, according to the Kyrgyz, received its name from a Kalmyk whom the Kyrgyz drove into the upper reaches of the spring at the foot of Mount Ulkon-Tura and forced to surrender.

Another attraction of this place is a mysterious cave with a wooden staircase and a metal cauldron (at least according to the Kyrgyz). It is located on the eastern slope of Ulkon-Tura, on the side facing the Tuty-uzen River, which also flows into Boroldai from the left.

This cave, they say, can only be accessed from the Dzhailya-usha plateau, on the upper reaches of the Kuturgan, Sary-bulak, Karaungur, and Kaprchakty rivers. But since the cave can now only be entered by ropes up to a hundred fathoms long, I intend to travel there only in a group of several people.

"Having learned from the editorial note of the Turkestan Gazette to my article 'On the Boroldai Letters' that the Turkestan Circle of Archaeology Lovers intends to reprint it and lithograph the symbols I have provided, I am sending you several more examples of such symbols.

The cell outlined in red pencil represents an individual stone with a symbol depicted on it. The grouping of symbols on the sheet of paper sent is arbitrary; it does not represent their sequence within a row of stones, but rather copies what seemed easy to reproduce by hand.

The symbols were examined by Mr. Shpotin and me alternately through binoculars: Mr. Shpotin examined the symbols through the binoculars while running his finger over the inscriptions to discern them more clearly, as the connections between the lines and dashes were unclear.

On many stones, the connections between the symbols are very complex and intricate, so we did not copy them. The images of animals and people on the stones are carefully carved, not intermingled with the symbols. The current state of the stones left such an impression on me that the symbols on them have existed for at least a thousand years.

I once heard that there was once a large city in the area of Terekty, but I have never had the opportunity to verify this. The name of the Boroldai River is apparently Mongolian. For example, the name "Boroldai Su-yalba" appears in Mongolian legends for a character:

"Boroldai-Ku" is a character in a Mongolian folktale (See N.G. Potanin, "Essays on Northwestern Mongolia." Vol. II, Ethnographic Materials. St. Petersburg, 1881, pp. 171-172, and Vol. IV, pp. 381-382, 1898-1899); but I see no connection between the names and the script. In Vol. II, Table XXVI, Potanin cites tamgas: but there are no similarities to those I am sending you.

In any case, the signs cited, in my opinion, belong not to the Kalmyks, but to another people, but which one -that is the whole question."

Authority:

Petr Ivanovich Komarov. 1904

"Protocols of the Turkestan Circle of Archaeology Lovers." Issue 10, Tashkent, 1905.\

Photos by:

Alexander Petrov.