Вы здесь

M. Pogrebetsky 1929 expedition to Khan-Tengri.

View of Khan-Tengri from Ketmen ridge.

"Whoever has drunk water from our rivers and seen Celestial Mountains - Tien-Shan - will return here again."

Words of an old Berkuchi from M. Pogrebetsky's expedition.

M. Pogrebetsky 1929 expedition to Khan-Tengri Peak.

In 1929, a special expedition led by M.T. Pogrebetsky explored the approaches to Khan Tengri. This was a time of rampant banditry in the regions of Central Asia. A small detachment of border guards, commanded by Ivan Golovin, was assigned to M.T. Pogrebetsky's expedition.

Understanding the complexity of the situation in which the members of his small expedition would be working, M.T. Pogrebetsky asked the border guard commander to find a suitable guide who knew the alternative routes to the foot of Khan- Tengri.

To ensure security along the approaches to the main expedition area, Ivan Golovin brought the renowned ergenchi (hunter) and guide Nikolai Vasilyevich Nabokov, along with his 20-year-old son Mikhail, to M.T. Pogrebetsky. Nabokov had lived his entire life in the Tien-Shan and had even served as a guide on the expedition of the renowned German geographer and explorer Gottfried Merzbacher.

Many decades later, at a site near Nansen Peak, young climbers found spent cartridges from three-line rifles and the remains of decayed horse harnesses. This was the site of a clash between Ivan Golovin's detachment and Dzhantay's gang.

With the help of current border guards and local residents, the climbers erected a memorial plaque at a lofty height with the inscription: "Here, at Nansen Peak, in September 1929, six border guards, led by the assistant to the outpost commander, I.S. Golovin, fought to the death, protecting the first Soviet expedition to Khan-Tengri, led by M.T. Pogrebetsky, from the Basmachi."

Route of M. Pogrebetsky's Ukrainian expedition in 1929:

Frunze – Boom Gorge – Lake Issyk-Kul – Rybachye – Przhevalsk (sailed on the motor ship "Progress Kirgizstana" for one night) – Karkarinskaya Fair (purchase of horses) – Sarydzhas and Kegen River Valley – Sarydzhas village – Karasaz village – Lake Tuzkol (Baragobasu, observing Khan Tengri with binoculars) – (M. Pogrebetsky's trip to Narynkol village) – the expedition departed for Kokpak village – Tekes River and village (ford) – Narynkol village – Karatau Mountains (actually Sarykaptal) – Issykatkan Pass – Ulken-Kokpak River Valley – Kokpak Pass 3482 m – Sarydzhaz River Valley – Tyuz River Valley – Tyuz Pass 4001 m – Maublak tract (right bank of the Inylchek River) – South Inylchek Glacier (7 days of walking on the glacier) – lake (apparently Merzbacher, but still unnamed) – then South Inylchek Glacier – 3-day return via Tyuz Pass – Sarydzhaz Valley.

Expedition once saw Khan-Tengri from glacier.

In 1929, the All-Ukrainian Scientific Association of Oriental Studies, the People's Commissariat of Education, and the Supreme Council of Physical Culture organized the first reconnaissance expedition to the Khan Tengri massif. For six days, the Moscow-Frunze train sped us past Samara, Orenburg, Aktobe, Kyzyl-Orda, and Arys, through soft, undulating, boundless steppes, floodplains with shrubs and forests, salt marshes with thickets of gray wormwood, and semi-deserts with sand dunes and tumbleweeds.

On the sixth day, we arrived in the capital of the Kyrgyz Republic, and the day after that, our car crossed the Buam Gorge, the Aleksandrovsky Range, and its eastern extension, the Kungey-Ala-Tau. The mountains recede into the distance. The horizon recedes, and the car flies through the Issyk-Kul Valley.

From the car, the blue surface of the lake is visible, and beyond it, to the south, rivaling the whiteness of the clouds, stand the jagged ridges of Mount Terskey. The car accelerates, and the lake's expanse expands, filling the entire horizon. At the eastern end, glittering ice masses prop up the sky with their peaks. Before us lies the Central Tien-Shan.

That evening, we boarded the steamship "Progress Kyrgyzstan." This ship was launched in 1926. Before Soviet rule, Issyk-Kul and Kyrgyzstan had never seen a steamship. The last bales were lowered into the hold, the hatches were slid shut.

The stevedores disembarked and pulled back the gangplanks. The winches rattled. The ship's hull began to shake, and the rare lights of the village of Rybachye began to recede and fade. A clear night. Stars peered out from the depths of the sky and were reflected overboard in the calm surface of the water.

Massive mountains Along the sides of the lake, they accompany us. In the morning, the ship approaches the Karakol pier. On the high bank stands a monument to Przhevalsky, depicting a rock on which an eagle has rapaciously seized and trampled a map of Asia in its talons.

The monument makes no secret of the expansionist policy of Tsarist Russia, which it pursued in its colonies. It's eleven kilometers from the pier to the city. In the center is a bazaar. On one side of the bazaar are carts with peasant food; on the other, chailans and ashkhans with low bunks covered with felt mats and shaggy Kyrgyz rugs are set up.

White-bearded Uzbeks in turbans and tanned Kyrgyz in sheepskin hats drink tea. Steaming chilim passes from hand to hand. Nearby, dumplings and fatty manti are steaming in large sieves. Cauldrons hold rice pilaf, shurpa boils, and steam rises from boiled rams' heads and liver on the stove.

A Kyrgyz man, wearing a camel-hair chapan, sits on his haunches near the teahouse, his chest open the color of unrefined copper, pouring kumiss from a soft chanash into bowls. With dirty fingers, he scrapes grease and stuck hair from the edges of the bowls, licks his finger, and circles the bowl again, this time clean.

On the ground, merchants have laid out thick felt mats for yurt tents, korzhuns, patterned "tekemet" rugs, hair lassos, and horse harnesses. Customers ride on low-slung horses or saddled oxen, on shaggy yaks and camels. Men in wadded chapans, women in long beshmets with white turbans on their heads; girls in fox-fur hats, from under which tarry braids peek out.

The bazaar defines the city's identity. The settlers' carts and Uzbek ashkhans represent the sedentary world. The Kyrgyz horsemen who came from the mountains represent the nomadic world. On the very border of these two worlds stands the city of Karakol, serving as a link between sedentary and nomadic life.

Built in 1869 as an outpost of the colonialists' militant designs, it now serves as an outpost of Soviet culture, encroaching on the remnants of the semi-tribal, semi-feudal way of life of the nomads. From Karakol we left to purchase horses for an expedition to the Karkara Fair in Kazakhstan.

The fair was in full swing. Cossacks, Kyrgyz, Russians, and Ukrainians had arrived here with wool, felt, rawhide, furs, flocks of sheep, and herds of horses to exchange their raw materials for goods. This mass of people, mounted and on foot, moved in crowds, clogging the streets, forming vicious circles around the fortune teller or the Ulgenchi.

It was difficult to get through the wall of robes, chapans, beshmets, sheepskin coats, and svitkas to the stalls. We would be staying here for several days until we had purchased horses. We had chosen a spot for our tents near two yurts, which were different in size and appearance from all the others in the clearing.

One of these yurts bore an inscription in Kazakh and Russian:

- "Workers of the world, unite!"

The red yurt of the Karkaria district, belonging to the fair committee. Inside the yurt is a table with newspapers and magazines. Posters and a wall newspaper from the fair committee's Komsomol cell hang on the walls. The red yurt is a center of Soviet culture in the nomadic regions of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

It is a collapsible propaganda outlet, a club and school, moving along mountain trails on packs. Its workers are fighters on that fierce front where the struggle is being waged against centuries-old darkness, superstition, the influence of mules, riches, and manaps, polygamy, kalym, underage marriage, the enslavement of women, and everyday diseases.

General meetings and rallies are held near the red yurts. Today, a rally is being held to mark the fifteenth anniversary of the start of the world imperialist war. A Cossack stands on an improvised platform. A triple ring of horsemen surrounds them - new groups with banners are constantly arriving.

- Yoldashlyar!

The crowd falls silent. A heated speech pours from the podium. The speaker speaks of the cruel enslavement of the Central Asian peoples by the tsarist satraps, the expropriation of the best lands, national oppression, tyranny, and bribery, the sowing of antagonism between the natives and the settlers.

The October Revolution put an end to this tyranny forever. Oppressed nationalities gained self-determination. Autonomous republics were organized, national military units were created. Cultural development is underway in the most remote corners of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

The International Banner - the red flag - the symbol of the liberation of the workers of all nations flutters over Kazakhstan as well. The orchestra plays the "Internationale." The banners are raised. The nomads straighten up in their saddles. The national militia salutes.

Our spirits are high. Having bought horses in Karkara, we We set out with our packs for Narynkol, the last village bordering Xinjiang, where we hoped to finally prepare for the mountains. Along the way, we stopped at Lake Baragobasu, where we saw Khan-Tengri for the first time.

We arrived at the lake late in the evening and went to bed, but were awakened early the next morning, as Khan-Tengri is only visible from here at dawn. Twilight was fading, and dawn was just beginning to dawn. We were in a flat basin. To the right, heavily smoothed clay mountains rose, at the foot of which a lake with dark, leaden water slumbered.

To the southeast, where Khan-Tengri should have been, it was still dark. Our photographers and cameramen were preparing their cameras and adjusting filters. But then the first rays of light appeared in the east, and like a magical scene, a chain of icy mountains appeared before us across the entire horizon.

Almost in the middle of this chain rose a white pyramid with steep edges, striking with its exceptional height and the steepness of its slopes. We stood in deep thought. How to penetrate this icy world? From here, it seemed impossible. Now that five years have passed, during which I have seen Khan-Tengri from all sides and from various heights, I can say that from nowhere does Khan-Tengri appear so majestic, menacing, and inaccessible as from Lake Baragobasu.

I trained my binoculars; from here, the Khan-Tengri pyramid appeared triangular; its eastern edge was steeper than the northwestern one. The slopes of the northern face dropped steeply, and snow lingered only here and there on small ledges.

Despite the small amount of snow on Khan Tengri, its summit appeared white, as it was entirely made of marble.

My friend, Franz Sauberer, a member of the Austrian tourist association "Naturfreund"*, took his binoculars away and said,

- "Yes, this is a very cold place."

The second time I saw Khan-Tengri was from the Ketmen Mountains at sunset. We needed to contact the Jarkent border detachment about access to the border zone, and we left Narynkol for the last point in the mountains reached by the telephone line, which was being built at the time.

After fording the Tekes, we began to ascend the gentle slopes of Karatau. The higher the trail climbed, the higher the wall of snow-capped mountains rose behind us. One sharp peak stood out in particular for the steepness of its slopes and the grandeur of its form, and I asked our horseman, Bordankul, what kind of mountain it was.

"Barnak chon too, Comrade Chief," he replied, without naming the mountain.

"Turpan kerem, Karkara kerem, all visible."

"Kan-to bu?" I asked again.

"Kan-to, Kan-to, Comrade Chief. Kan-to," he nodded.

Soft shadows fell from the mountains onto the valley. The sun gilded the tops of the ridges. Evening was approaching. We were climbing the Issykatkan Pass, leading to the Ketmen Mountains.

- "Turn around!"

From edge to edge, along the entire horizon, in glaciers and snow, stands the great Tien-Shan wall. It all glows with the golden-orange and red hues of the sunset, and Khan Tengri blazes above like a giant faceted ruby set in a dark turquoise sky.

But then the sun sinks deeper below the horizon, the sky darkens, the colors fade, the orange tones give way to pink, pink-violet, and only Khan Tengri glows with the blood-red fire of molten metal against the dark sky. Gradually, the mountains plunge into darkness and finally dissolve completely in the deepening twilight.

Khan-Tengri, too, slowly fades behind them. On the way to Inylchek, we twice saw Khan-Tengri from afar: from the Kapkah Pass, from where it no longer presented such a menacing appearance, being much closer to us, and from Saryjas, where Zauberer and I climbed to observe the northern slope of the peak.

We unexpectedly found ourselves witnessing a very rare phenomenon: after sunset and the darkness that followed, the mountains suddenly lit up again with orange and purple hues. This phenomenon is known as the "Alpine afterburn." It is explained by the property of small droplets in the atmosphere to refract the last rays of the sun, hidden from us, and cast them onto the white surface of the snowy slopes.

On the way to Khan-Tengri, it wasn't only nature that created obstacles for us. At that time, bands of Basmachi were still roaming the mountains, and we had to deal with them twice. The first encounter took place in the Tyuz Valley, where we camped before crossing to Inylchek.

That night, through my sleep, I heard shots. They followed one after another, close to us, and the sounds became increasingly frequent. Sleep still held me tight, and it seemed as if our hunters were shooting mountain sheep in the mountains. I turned over to sleep, but heard the whistle of bullets above the tent.

In the darkness, my eyes could barely make out my comrades hurrying out of their sleeping bags. From behind the tent, I could hear the voice of one of our porters: "Tiybe, bu at ekspeditsii" (Don't touch them, these are the expedition's horses), and a voice answered, very close:

"Zhogol. Yattan gure. Men atamyn" (Go away. I'll shoot).

Old Nabokov approaches and says, quite calmly:

"Comrade Chief, the gang has taken the horses. The gang has gone down the valley, where a detachment of border guards assigned to us for protection is currently stationed. I'm afraid they'll be caught unawares. We must hurry and warn them while it's still dark and we can pass unnoticed."

Zauberer and Bardankul agreed with me. We run, crouched, under the cover of the high bank, so as not to be given away by our own silhouettes. After a kilometer, I can no longer see Franz or Bardankul behind me. They've apparently crouched down, and Franz waves me to do the same.

Bardankul peers intently; I peer too, and with difficulty make out the barely visible outlines of mounted figures. Bardankul rises and begins to shout:

- Men Bardan-ku-ul, men Bardan-ku-ulkh (I am Bardankul).

I tug at his sleeve.

- Kim bu (who is this)?

Bardankul is silent and peers even more intently at the indistinct figures. The cautious approaching footsteps and the voices of unfamiliar Kyrgyz are heard.

- "Gang!" flashes through my mind.

Suddenly Bardankul raises both hands and lets out a desperate cry:

- Hey, alar, atyb zhatyshat atba. Don't shoot, don't shoot, comrade, my Bardankul. Chief of the Birge. (Oh, they're shooting. Don't shoot, I am Bardankul. The chief is close.)

I see horsemen already close; They lower their rifles and gallop toward us. These are Red Army soldiers, accompanied by Kyrgyz from the village that migrated to Tyuz yesterday.

- "What are you doing here?" asks the detachment commander, Golovin, perplexed.

- "Did you know I almost shot you?"

The detachment sets off in pursuit, and we are discussing our transition to a dismounted position, when suddenly, out of breath, the horseman Abdu-Kadir runs toward us and shouts from afar:

- "At bar, comrade commander (we have horses)."

It turns out the horses were grazing behind a hillock, and the horsemen, seeing the gang driving the herd, assumed it was our horses that had been stolen. Everything turned out well. At the head of the valley is the Tyuz Pass. It's so steep that it seems unlikely that horses could have climbed it.

The girths, breastplates, and packs are carefully checked. The head of the border detachment, Golovin, and two porters are the first to break a path in the snow. From below, we can see how difficult it is for the horses due to the steepness and deep snow.

Trushenko's horse falls three times in a row, and his owner has to descend and then climb back up again three times. Every five minutes, the first group stops to give the horses a rest. Now our group carries the packs. No matter how carefully we adjust the packs, they tip backwards and threaten to drag the horses down.

We have to remove some of the loads and carry them, but even with the lighter load, the horses are still exhausted. Snowballs fly from under their feet and, rolling into large boulders, fall far down into the valley. By noon, we reach the pass. As soon as we peered over the snow-capped ridge of the pass, the fog hanging in the valley descended like a cloud halfway down the slope, revealing the valley and ridge.

Our horsemen, accustomed to all sorts of mountain scenes, couldn't help but exclaim. Opposite the pass stood gigantic cliffs with sharp jagged edges, wild glaciers, and dark patches of spruce forests on ancient alluvial deposits. Two kilometers below us, a wide valley stretched out in a slightly curved line, its convex side facing south.

Its bottom was bare of vegetation, and only the channels of the Inylchek River twisted like gray snakes among the pebbles and sand. To the left, turning northeast, lay a gigantic glacier. Its surface is covered with rock debris for many kilometers, and only at the very top are clear ice and snow visible.

On the descent near the Mai-bulak tract, we fed the horses. One of the Red Army soldiers asked me for my binoculars.

- "A man," he said, "and he looks Russian."

Two climbers with heavy backpacks were ascending the clearing. They could only be comrades from the group of Muscovite Myssovsky, who was supposed to join our expedition, but we had missed him. The comrades who approached were climbers V. Gusev and N. Mikhailov. While I.E. Myssovsky, who had lingered below, approached us, another living creature emerged into the clearing: a large, two-year-old bear, a black color rare in the Tie- Shan.

He looked around in surprise and sniffed the new scents. His appearance was so unexpected that for the first minute everyone was confused and only shouted:

- Look, a bear! Then everyone rushed to their rifles and a flurry of gunfire erupted. The bear turned sharply and charged up the very path our caravan had just taken. Despite its bulk, it ran fast; the bullets landed almost right next to it, but not a single one hit it.

Finally, it dove off to the side and disappeared. The shooting ceased. The hunters exchanged awkward glances and chuckled at each other. The interrupted conversation resumed. The Muscovites explained that they had managed to cross the glacier to the lake, but then ran out of food and were forced to turn back.

I gave them a horse and a guide to the pass, and we said our goodbyes. From terrace to terrace, we descended the washed-out surface of the southern slope until we emerged into the valley. The crossing began. Fords in the mountains don't always pass unpunished.

During floods, especially in years when heavy precipitation accumulates masses of snow in the mountains, rivers overflow their banks, carrying torrents of muddy water with a terrifying force and the noise of rolling boulders. To better withstand the onslaught of the water, we lined up our horses, head to head, with the weaker ones in the middle, but the water still knocked the outer horses to the side.

The sun was setting when we reached a forest clearing located on the left bank of the highest peak in the Inylchek Range. Our route through valleys and passes had ended. We set up base and, from here, a few days later, set out onto the gigantic Inylchek Glacier.

The dark tongue of this glacier fills the entire width of the valley. Its main stream emerges from the left, carrying turbid, silt-laden water, rolling pebbles and rubble, depositing them on its capricious, ever-changing banks. The glacier's tongue descends precipitously into the valley.

I have never seen such a dense moraine cover on any glacier. Enormous banks of rubble rise here like frozen dunes, giving the glacier the appearance of a rocky desert. The dark, easily eroded shale rocks experience sharp temperature fluctuations daily due to the continental climate and altitude.

They crack and loosen, and a stream of rock from both slopes flows continuously onto the glacier. Rockfalls and avalanches cascade down the slopes, piling up cones of talus. With a distinctive whistle, the rocks fall singly, gradually covering the glacier in a continuous blanket.

Leading a caravan across the surface of such a glacier is extremely difficult. A crevasse gapes across the path, a lake with sheer ice walls blocks the way, or you emerge onto a sloping spot barely covered with rubble, and the horses, losing their footing, slip, glancing sideways at the terrifying ice abysses, trembling with fear, and breaking out in a sweat from nervous and physical exertion.

The men become nervous, the horses lose strength, and have to be brought back. Soon, chunks of white ice begin to emerge from the broad body of the glacier, covered in debris. The higher we climb, the more numerous they become. The ice chunks, like waves, advance northward, turning northeast.

Facing us, from the center of the glacier, rises the black buttress of a shale ridge extending from the east. Its cape faces the valley, its sharp chest seeming to loosen the icy chaos that had gripped it, splitting the glacier into two arms - northern and southern.

The northern arm is narrower than the southern, and at its very mouth, it closes into a lake, on the surface of which floats a dense mass of ice floes of the most bizarre shapes. Since the ice floes in the lake, as it seemed from here, were almost touching each other, we decided to attempt a direct crossing of the lake across the ice floes and reach Khan-Tengri from the north.

However, when we approached the ice mountains, they turned out to be separated from each other by thawed patches, forcing us to move by leaps and bounds. High ice walls surrounded us, blocking our path. How many times, having expended a great deal of time and effort, we, having reached a sheer wall or a wide thawed patch, had to turn back and start the journey all over again.

But we continued to move forward for a long time, until a wide strip of ice-free water stretching from south to north blocked our path. We soon realized that equally wide strips of ice-free water were cutting us off from the left and right banks. Dusk was falling, and fog was moving in.

The red patches we had used to mark the way ahead were no longer visible. The snow bridges we had previously crossed became loose from the damp fog and sank underfoot. The ice floes sank, tilted, and changed shape, and in the gathering darkness it was impossible to tell how far we were from the icy shore.

Losing our last strength, constantly falling into water and wet snow, we only emerged onto firmer ice around two in the morning and fell asleep like logs, a kilometer from the camp. In the morning, I sent a note to the cameramen remaining at the camp on the moraine.

The scenes we witnessed on the lake: ice castles and towers, covered in snow and sparkling in the sun with myriads of snow crystals, blue lakes nestled in snowy shores, waterfalls, translucent grottoes, hanging stalactites sparkling with every color of the rainbow - they could have made for some stunning film footage.

This lake owes its origin to a basin where waters flow from side gorges and are held back by an ice dam enclosing the lake from the west. Periodically, as our observations in subsequent years showed, the waters filling the lake seek an outlet, break through the ice dam, and escape, partly through subglacial passages, partly through the randkluft, along the right slope.

Then the Inylchek River becomes a menacing presence. It overflows its banks, filling the valley. Leaden wave crests line its surface, and the incessant roar of the water and rolling boulders fills the valley. In 1932, returning from Khan-Tengri, we stopped by a lake.

In recent days, there had been a constant roar, as if from avalanches, although no evidence of intense activity was observed. I decided to go to the lake. The closer we got, the louder the roar became, and the more obvious it became that it was not caused by avalanches.

The ice masses towering ahead, however, obscured the lake and prevented us from seeing what was happening there. Occasionally, a dusting of snow would fly up, followed by a roar. We climbed a cliff, and immediately the entire scene of natural destruction appeared before us.

The water in the lake had disappeared. Only isolated puddles glistened on the surface of large ice floes, between which the muddy bottom was visible. From the west, a white wall of ice floes, exposed from top to bottom, advanced on the lake.

From time to time, the nearest ones, for no apparent reason, began to slowly tilt, break at the base, settle, and crash down, followed by clouds of icy spray. The same picture was in the center of the basin, where swarms of icebergs pressed against each other with monstrous force, pushing individual chunks upward.

A constant roar and swirls of snow dust swirled over the lake. The failure to find a route across the lake forced us to cross to the southern glacier, along which the group consisting of Bagmut, Kolyada, Redak, and Shimansky had set out. We crossed this glacier in three days.

Opposite us, on the northern ridge, rose a black, pointed peak, over 6,000 meters high. Counting from the western end of the range, it was the seventh. According to a two-mile-long topographic map, on which the ice-dividing ridge is cut like an island among the white spots, the eighth peak should be Khan-Tengri, and therefore, it is currently obscured by this black peak.

If this is indeed the case, then today, in just two or three hours, we will be able to see Khan-Tengri up close. This excites us and gives us renewed strength. To the right of the black peak, a steep ridge appeared, descending like a buttress to the glacier.

It curved in a semicircle, turning southwest and forming a cirque with steep walls. The further we advanced, the higher the ridge became, and it seemed the summit would emerge from behind the black mountain at any moment. But the summit remained hidden, remaining thickly shrouded in clouds.

Clouds were gathering, dampening our spirits, and yet we were already on our seventh day on the glacier. The return journey would take three days, and the border detachment remaining at the Inylchek base had agreed with us that they could wait for us for no more than ten days.

- How long would the cloud cover last - an hour, a day, or even longer?

The reader will understand our state. Oh, if only the fiercest wind would blow and scatter the clouds! We waited in agonizing suspense for a change in the weather. And suddenly, the clouds that had accumulated around the mysterious peak began to disperse.

Some of them rushed upward, the middle part spread out, brightened, broke into gossamer lace - and a white cone appeared in the cloud halo. "Khan-Tengri," we blurted out. Before us stood a monolithic rock pyramid, carved from solid marble and fused into an icy pedestal.

From here, Khan-Tengri's summit seemed lower and squatter than from the vantage points from which we had previously observed it. This was understandable, as we were so close that perspective was distorted. Furthermore, the sheer size of the colossus before us was greatly obscured by the black cliff of the neighboring peak.

We were unable to get a closer look at Khan-Tengri. Clouds gathered again around its summit, fog descended, obscuring the peak. On the return journey, two days later, when we were below the lake, already not far from the glacier's tongue, the tall figure of our horseman Nurgadzhi unexpectedly appeared.

He waved a white piece of paper and, jumping from rock to rock, hurried toward us. Before he even reached the spot, he began relaying the news:

"Comrade Chief, what happened? A gang came, I shot too, he shot too. Here, please, is the paper, read it quickly."

On a page torn from his field notebook, Comrade Golovin, the commander of the border detachment accompanying us, wrote:

"Comrade Pogrebetsky. I ask you not to delay for another hour, as under the current circumstances I cannot remain here for another minute. On August 28th, Dzhantay's band, 50 men strong, attacked us. The band was repelled. On August 31st, they repeated the attack and were again repelled. I suspect that in the very near future, the band will repeat the attack with a stronger force. I look forward to your speedy return. Greetings, Golovin."

We hastily loaded our belongings onto the horses, and the caravan moved down the glacier. It was drizzling, the rocks became slippery, and a continuous stream ran across the entire glacier. The Inylchek River had overflowed, and the water was knocking the horses down.

We arrived at the base. There were no people in sight - almost everyone was at their posts. Golovin, leisurely and smiling, as if it were the most ordinary thing, recounted the gang's raid. We placed ourselves at his disposal as commander-in-chief of all armed forces on Inylchek.

Campfires were prohibited, the horses were led to the cliffs behind the camp, and guards were posted all around. But the night passed peacefully, and at dawn we abandoned the base, crossed the Inylchek Valley, crossed the Tyuz, and descended to Saryjas.

At Saryjas, our paths parted with the border detachment. All the best, comrade border guards! Thank you for your selfless assistance, full of risk and courage.

Until next time!

Authority and photos by:

M.T. Pogrebetsky. "Ukrainian Worker." Kharkov. 1935.

Ilya Evgenievich Vetrov's book. "First to Khan-Tengri. Travels of M.T. Pogrebetsky." 1971.

Journey to Semirechye in 1929.

Those who dreamed of distant travels will never forget their first trip. The day when, having carefully planned the route and every detail of the trip, you say goodbye to your hometown will leave an indelible mark on your memory. And for a person who has once tasted the ocean surf or breathed in the icy mountain wind, the time of travel will be the happiest in life.

Such was Pogrebetsky's time traveling through the Mzymta River gorge, the picturesque gorges of Karachay, his ascent of the Wetterhorn and Schaarhorn in the Bernese Alps, and, finally, his hikes in the Tien Shan and the ascent To the snowy Dzhindysu.

In those years, there was no good mountaineering equipment - storm suits, reliable ropes, pitons - nor any useful maps. The mountains were full of dangers. But be that as it may, the Tien Shan Mountains enchanted Pogrebetsky. "Whoever has drunk water from our rivers and seen the Heavenly Mountains - the Tien-Shan - will return here again" - these words of an old berkuchi (golden eagle hunter) remained in his memory for a long time.

A persistent and hardworking man, Pogrebetsky read a lot, spending late nights in libraries, rapturously studying the works of Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, Kozlov, Przhevalsky, the German geographer Merzbacher, and other eminent travelers who, at various times, attempted to penetrate the depths of the Heavenly Mountains, to the mysterious Khan-Tengri massif.

And in his mind, visions were forming. Bold plans for expeditions, research, and discoveries. In February 1929, Pogrebetsky received an invitation from Professor Gladstern, head of the Ukrainian Association of Oriental Studies, to visit the association, of which he had been a full member for many years.

"I have good news for you, dear colleague," the professor addressed him. "The expedition has been approved and considerable funds have been allocated for its implementation." Pogrebetsky approached the map hanging in Gladstern's office. It clearly depicted the dark brown contours of the Tien-Shan ranges with a blank spot representing the mysterious, as yet unexplored and unmapped Central Tien-Shan.

Pogrebetsky knew that the expedition to the Tien-Shan would face challenges. A long and dangerous journey along the Sarydzhaz River valley awaited them, along with Basmachi forces entrenched in wild gorges, rockfalls on the cliffs, deep crevasses, and icy seracs.

On the glaciers, fierce snowstorms rage for weeks. Before Pogrebetskoye, few Europeans had visited these mountains, and those who had, like the German geographer Merzbacher, believed that "the peaks of the Tien Shan are unsuitable for mountaineering."

Pogrebetsky placed the small map of the Central Tien-Shan he had brought with him on the table and began drawing some geometric shapes on it with a red pencil. Pointing to a triangle he had drawn to the right of the enormous glacier, he said:

"Khan Tengri will be the most difficult..."

"Mysterious Lord of the Spirit," "Mountain of Blood" - that's what the locals called the Tien Shan giant, because at sunset, Khan-Tengri turns a bloody red.

Tien-Shan blank spots required topographic surveys, its ore wealth required geological exploration. At that time, our country's national economy was particularly in need of the raw materials and minerals undoubtedly hidden in the depths of the Tien-Shan mountains.

Therefore, in defining the objectives of the Tien-Shan expedition, Pogrebetsky proposed a broad program of scientific work. A neurologist by profession, Pogrebetsky was also a well-rounded man. He was knowledgeable in painting, drew, enjoyed music, and was well versed in history and ancient philosophers.

Books were his closest and best friends. His library contained rare editions, works by scientists, and eminent travelers. And when Pogrebetsky visited the mountains, he became fascinated with glaciology and meteorology. In 1927, he studied the culture of the peoples of Dagestan, and that same year, he led archaeological and ethnographic expeditions to the Talysh mountain region in Eastern Transcaucasia.

When the Republican Museum of Contemporary Culture and Life of the Peoples of the East was established in Kharkov, he took an active part in its work. He led one of the first Ukrainian expeditions to Central Asia. In early March 1929, Pogrebetsky fully staffed the expedition to the Tien-Shan.

The expedition included Sergei Shimansky, an encyclopedic engineer and talented color photographer; Ivan Bagmut, then still an aspiring writer, a man of great determination and perseverance; and Nikolai Kolyada, a gifted musician and composer.

Like Bagmut, Kolyada was an avid mountaineer and had numerous responsibilities on the expedition, including collecting ethnographic material. The expedition also included Ivan Laziyev, already a renowned documentary and newsreel cameraman, and Arkady Redak, an employee of the Kharkiv Worker newspaper.

The seventh member of the expedition was Franz Sauberer, a member of the Ukrainian Tourist Society. Pogrebetsky met Franz Sauberer in Kharkiv, at the People's Commissariat of Education. He was a native of the Italian village of Merano in the Tyrolean Alps, graduated from a specialized mountain and alpine school, and was a professional guide in Innsbruck.

Franz Sauberer was a communist. He was arrested several times for participating in anti-government rallies and political demonstrations. In 1927, facing imprisonment, he emigrated to the Soviet Union. By the end of May 1929, preparations for the expedition were complete.

In those years, mountaineering equipment was not manufactured in Kharkov, nor in other cities across the country, so it's easy to imagine the effort it took Pogrebetsky to acquire ice axes, crampons, sleeping bags, tents, and other equipment.

At the end of July, the first Ukrainian expedition departed Kharkov. For six days, the train traveled east. The Aral Sea was behind them. Beyond the Baigakum station, the Karatau Mountains appeared in the distant haze, with the northern spurs of the Tien-Shan ranges to the south.

Arys... Transfer to the line leading to Frunze. The dry riverbed of the Abylkair flashed past, and the full-flowing Kuragaty River with its numerous tributaries appeared ahead. The landscape changed. Mountains towered in a blue haze. Through a break in the cirrus clouds, rocky peaks shone at an inaccessible height, whitened with the gray of eternal snow.

This was the Tien-Shan. The Celestial Mountains... "We gazed at them without stopping," Pogrebetsky wrote in his notes. "And everyone was thinking the same thing... A short time will pass, and the Soviet people will begin to advance on these peaks.

We, the first scouts, must open the way for this advance, the path to the very heart of the Celestial Mountains." And everyone felt a great responsibility for the assigned mission. Will we be able to cope with him?.." The train meandered, stopping frequently, and plunged into the darkness of long tunnels.

At dawn on July 12, the express slowly pulled into the Frunze station. In Frunze, Pogrebetsky needed to complete paperwork, consult with local historians, obtain dry alcohol, film, and much more. On the fourth day of their stay in Frunze, the car assigned to the expedition by the post office was already parked early in the morning behind the high wall of an adobe house.

The expedition members settled in among backpacks, sacks of biscuits, crackers, canned goods, sugar, and bundles of rope. The car set off. Picking up speed, the battered Amovka bounced over potholes and ruts, kicking up clouds of dark, thick dust.

The dust hung over the dirt road, seeping into the truck's bed and cabin, coating their clothes and faces, and crunching between their teeth. The mountains approached. The car climbed ever higher along the narrow road, winding whimsically among the rocks.

The mountains were already looming, seemingly at an inaccessible height, crowding each other. To the west, the steep spurs of the Kyrgyz Alatau stretched almost to the sky, to the east, the Kungei Alatau. Between the two ridges, the turbulent Chu River roared and foamed in a deep, rocky gorge.

The Boam Gorge began. The road wound continually among overhanging cliffs. Upon exiting the gorge, the expanse of Lake Issyk-Kul opened up before the travelers' eyes. Issyk-Kul greeted the travelers unwelcomingly. Winds blew, and the lake was covered in folds of waves.

But the weather soon improved, and the travelers, having loaded their expedition gear onto the steamer, left the village of Rybachye. Night passed. There were no stops beyond Koysar, and two hours later, Karakol appeared on the high shore of the lake.

This place became widely known for a tragic event that occurred in 1888: the distinguished Russian explorer Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky fell ill here and soon died. In memory of this tireless explorer of Central Asia, Karakol was named after Przhevalsky, and a monument was erected in his honor on the steep bank of Issyk-Kul.

There were many people on the shore to greet them. For these remote places, the arrival of a steamer is a significant event. A girl with tightly braided hair stepped out from the crowd and timidly approached Pogrebetsky.

- "I'm Fatima."

"Tairova? Our translator. I'm happy to meet you," he said, extending his hand to the girl.

The matter of Fatima Tairova, the eighth member of the expedition, had been decided upon back in Kharkov. Before departure, Pogrebetsky received a letter: "I read about the Tien Shan expedition in Moscow newspapers," it read, "and decided to offer my services. When studying the peoples of the Tien-Shan, the expedition naturally cannot do without a translator.

I could be such a translator. I am a mountain dweller and know the customs of my people well. True, we have never roamed near Khan Tengri, and I have never been to this peak, but this will not prevent me from being useful. Besides this, I want to say: let no one think that I, as a woman, can cause trouble.

So, if my ardent desire is fulfilled, I will be happy." Fatima's wish came true, and she was accepted as a full member of the expedition. In Przhevalsk, Pogrebetsky was supposed to clarify the route to Khan Tengri and find people who had been to the upper reaches of the Inylchek River.

But no such people were found in the city. He only learned that the Basmachi Djantai was raiding the Inylchek valley. Djantai's herds grazed in the valley of this river, and rumor had it that the Basmachi robbed and killed those who passed through his "domain."

This information was not pleasant. The difficulties of trekking along uncharted mountain trails were compounded by the danger of attack by the Basmachi. But Pogrebetsky, despite this danger, decided not to postpone the expedition and press on.

The expedition needed riding and pack horses. There were none in Przhevalsk, so Pogrebetsky went to the fair in Karkara. Having crossed the Karkarinka River, the expedition immediately found itself in a swirling human hubbub, seething and turbulent in the very center of Karkara and all the adjacent streets.

In Karkara, Pogrebetsky bought good Torgout horses - short, unprepossessing in appearance, but hardy and undemanding on the road. On August 5th, leaving Karkara, the expedition caravan headed east, into the Tekes River valley. The river valley was hot and stuffy.

It became easier when the setting sun lessened its harshness on the ground. On the third day after leaving Karkara, the caravan approached a low pass, from which a domed peak immediately opened up, closing a beautiful gorge to the south.

The Chubortal Gorge began, with its thick, lush grass, silvery spruce trees, and thickets of sea buckthorn. Below, in the hollow where Pogrebetsky was approaching, five or six yurts stood between the tall poplars. Kazakh nomads lived in them.

Horses grazed and children played near the yurts. The expedition stopped for the night in Chubortal, and in the morning set out toward Narynkol. The altitude is 4,000 meters above sea level. In the Caucasus, snow always lies at this altitude, but here, there is lush grass and vibrant flowers.

North of the village of Kokpak, there is a small lake called Buradobusin. A few kilometers before it, the caravan stopped for the night. Early in the morning, when the first rays of the sun broke through, an endless chain of snow-capped mountains appeared on the horizon.

They seemed sculpted from ice from top to bottom.

Pogrebetsky was overcome with excitement. He was stunned by the sight. Here's what he writes about this fabulous spectacle:

"...A little to the east of the middle of this chain rises a white, pointed pyramid with steep edges...

"There he is, Khan Tengri - Lord of the Sky!..." "It's steeper than the northwestern one, and the slopes of the northern face, facing us, drop sharply down like a sheer wall, and the snow only clings here and there to small ledges... We all stand there, deep in thought. How to penetrate this icy world?.."

Three passes in Tien-Shan.

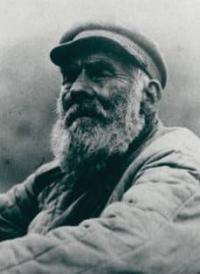

From Lake Buradobusin, part of the group returned to the village of Kokpak, while Pogrebetsky, Bardankul, and two young horsemen went to Narynkol, where they met Nikolai Vasilyevich Nabokov. Nabokov, an elderly man with handsome features and a long gray beard, but still cheerful and youthfully impetuous, was a renowned merginchi - hunter.

He had lived his entire life in the Tien Shan; he served as a guide on Gottfried Merzbacher's expedition, which was searching for a route to Khan Tengri. Merzbacher traveled to Khan Tengri from the Bayankol River valley across the Semenov and Mushketov glaciers, each time encountering the impassable Sarydzhaz ridge.

In 1902, Merzbacher heard of the Semirechye Cossack Nabokov and invited him to join his expedition. Traveling with Nabokov through the Tien Shan, Merzbacher successfully crossed Sarydzhaz and, between this ridge and the Khan Tengri massif, discovered a large valley with a glacier flowing through it.

Climbing the glacier, he also discovered that the glacier divided into two branches - northern and southern. Pogrebetsky was aware of the Munich geographer's discovery and, naturally, was delighted to meet Nabokov. From their conversation, he realized that the old man clearly remembered the route leading to Inylchek.

Having arranged a meeting with Golovin, the commander of an armed detachment assigned by local authorities to protect the expedition from the Basmachi, Pogrebetsky departed that same day for the village of Kokpak, where the expedition members were waiting.

At the end of August, having crossed a gentle rocky ridge, the expedition entered the valley of the Ulkun-Kokpak River, a right tributary of the Tekes. Birch trees, Tien Shan spruce, and juniper grew on the valley slopes. It was decided to set up camp and spend the night here.

The young riders began to unsaddle their horses, while Zauberer and Shimansky pitched the tents. It was very quiet. Even the restless mountain partridges were silent. Then suddenly, a song was heard from the forest, and armed horsemen appeared.

Nabokov rode ahead, his fur hat pulled low over his ears, a rifle slung over his shoulder. Behind him, Mikhail, his son, a young man of about twenty with a forelock, and then the tall, smiling Golovin, leading an armed detachment. Night fell suddenly, damp and cold, and with it, camp life gradually began to fade.

The next day, the caravan reached the Dzhapol ravine and soon entered a narrow gorge, where a sliver of sky was barely visible between the sheer walls. But then the gorge widened and suddenly filled with bright light and warmth. The air was filled with the scent of pine needles and mountain meadows, which now stretched for many kilometers.

It was midday when the Bazuabey ravine, the yurt, and its owner, Hamza Bazuabey, appeared in the distance, holding a golden eagle on his arm. About eighteen years ago, Hamza had caught a small golden eagle chick. Since then, Hamza and the golden eagle have been almost inseparable.

The golden eagle recognizes Hamza by his voice, knows his taigan dogs, takes meat from his hands, and with a single word, "Ait!" it soars into the sky like a candle and falls like a stone upon its prey. Neither wolf nor fox escapes the eagle's watchful eyes and strong claws...

Soon, the Bazuabey tract, with its sparse shrubs and squat juniper trees, twisted beyond recognition by the easterly winds, was left behind. The expedition approached the Kokpak Pass. The climb to the pass was steep and dangerous. From the pass, the snow-covered ranges of the Sarydzhaz Mountains were clearly visible to the south, and to the east, a huge peak loomed, like a white, marble-like tent.

Upon seeing it, the horsemen cried out in unison:

"Kan-to!" Kan-to!..

Pogrebetsky realized that Khan Tengri stood before him. He gazed at the majestic peak for a long time, and even as he began his descent toward Sarydzhaz, he involuntarily turned back to take another look. The descent from the pass turned out to be quite different from what they had initially planned.

Knowing the mountains well and quickly orienting himself to his surroundings, Pogrebetsky frequently adjusted the planned route, choosing the easiest and most convenient path. "To avoid losing altitude, let's traverse," he said. "We'll save time and energy."

Soon the expedition reached Kashkater, the pass adjacent to Kokpak. From Kashkater, small scree slopes stretched for many kilometers, leading into the Sarydzhaz River valley. Pogrebetsky repeatedly reined in his horse to examine the geological outcrops on the valley slopes.

He took individual rock samples with him, numbered them, and carefully placed them in his backpack for later study and description. Twice along the expedition's route, they encountered extinguished fires, traces of abandoned campsites, flocks of sheep, and large herds of horses.

Golovin believed these were traces of the Basmachi, and, to protect them, The expedition, starting from the Kokpak Pass, set up armed outposts during overnight stays to protect them from their surprise attacks. In the Sarydzhaz Valley, the expedition camp was located right on the riverbank.

From this valley, the route would lead to the Inylchek River, then along the Inylchek Valley to the Inylchek Glacier (where the river originated), and up the glacier to the Khan Tengri Massif. To scout the route to the neighboring valley, Pogrebetsky and Zauberer climbed the side ridge of the Sarydzhaz.

The sun was setting, but from the ridge, the upper reaches of the Sarydzhaz Valley and the Semenov Glacier were still visible. Mighty mountain ranges towered along the horizon from edge to edge, and above them towered the Lord of the Sky. But now the sun had sunk below the horizon, and night was falling.

"It's time for us to descend, Franz," said Pogrebetsky. And then, as if by magic, the mountains lit up, and long shadows - red, purple, and yellow - flared across the distant snowy slopes. They gave way to orange and violet streaks, and for a long time they glowed, sometimes brighter, sometimes paler, changing tones and colors before our eyes

"...We stood, stunned by this extraordinary and mysterious phenomenon, and found no explanation for it," Pogrebetsky later recounted. "...Unless it was due to the properties of those tiny, almost microscopic ice crystals that float in the upper layers of the atmosphere.

These crystals are capable of refracting and scattering light. At such a great height, they capture the sun's invisible rays, refract them into a colorful spectrum, and cast them back onto the white surface of the snowy slopes..." On the expedition's route lay the foaming tributary of the Sarydzhaz, the Tyuz River, and the pass of the same name.

Pogrebetsky knew that the Tyuz Pass in the Tien-Shan was one of the most difficult to access. Even the works of Russian military topographers who visited the pass in 1912 stated that to climb the pass, "steps must be cut in the ice, packs must be carried by hand or pulled with lassos, and the horses must be tripped, thrown onto felt mats, and pulled up the icy slope with lassos.

A climb of some five to seven fathoms requires ten hours of effort..." Pogrebetsky nevertheless believed that the crossing would be less difficult if the men and horses were given a good rest before setting out. But there was no time to rest. That night, through his sleep, Pogrebetsky heard shots from behind the tent, followed by the shouts of the drivers:

"Don't touch them! Those are the expedition's horses!"

Later it became clear: the Basmachi had taken the horses. There was no time to waste. "While it's still dark, we need to run to Golovin for reinforcements," Pogrebetsky decided. Along with Zauberer and Bardankul, they ran to the expedition's lower camp. Soon they saw armed horsemen.

It was Golovin's detachment. Hearing gunfire, Golovin ordered them to saddle their horses and head for the upper camp. Just as they were meeting Golovin, Abdukadir arrived and reported that all the horses had been found. While fleeing, the Basmachi had abandoned their horses, which Abdukadir found in a clearing near the camp.

Having broken camp, the expedition moved up the valley. The monotonously gray mountains turned pink and purple. The grassy slopes once again gave way to small scree slopes, which were very difficult to navigate. When the scree finally ended, Pogrebetsky and the advance detachment reached the snowy slopes of the Tyuz Pass.

A thick layer of snow still lay on the steep slopes of the pass. To climb the slope with pack animals, trenches had to be cut in the snow. But even in these trenches, the horses slipped, stumbled, fell, and tore their girths. The packs tumbled into the snow.

At one point during the crossing, a rock fragment, scattering chunks of ice and snow, flew toward the path of the packed horses. One of the horses took fright, shied sideways, and rolled down the slope. Every second was crucial. Pogrebetsky, sinking knee-deep in snow, ran to intercept the rolling horse.

He noticed a long pack rope winding down the slope, grabbed the end of it, threw it over an ice axe, and drove the axe into the snow. The rope tightened, and the horse, buried in the snow, began to stop. At midday on September 25, the caravan approached the upper part of the Tyuz Pass.

A sweeping panorama opened up from the pass. Through a break in the clouds, mountain ranges were visible, and below, the wide valley of Inylchek, dotted with dark spruce forests and a full-flowing river flowing through it. Far to the east, a huge glacier stretched, completely littered with black rock debris.

This was Inylchek, toward which the expedition lay. The first stop after Tyuz was at the Maibulak tract. The place turned out to be green, with soft, fragrant grass. Pogrebetsky raised his binoculars and spotted two men, bent under the weight of their backpacks, slowly ascending toward Maibulak. A tall man walked in front, followed by a short, bearded man.

Who were these men? And then Pogrebetsky remembered that a group of climbers, led by engineer Mysovsky, had set off for the Tien Shan. This group was supposed to penetrate the valley of the Northern Inylchek glacier and explore routes to the northern slopes of Khan Tengri.

When the men approached Pogrebetsky, it turned out that they were indeed the Moscow climbers Mysovsky, Gusev, and Mikhailov. Mysovsky told Pogrebetsky that the group had managed to penetrate the middle section of the Inylchek and explore the icy lake, but they could go no further: the path was blocked by icy cliffs.

Pogrebetsky gave Mysovsky a horse and a guide, and gave him a brief report on the expedition's progress, which he immediately wrote for sending to the Oriental Studies Association in Kharkov. The Inylchek is a capricious and swift river. It is especially swift during floods, when the snow melts high in the mountains.

Kyrgyz horses are accustomed to mountain rivers. Upon entering the water, they instinctively assume a comfortable position against the current and cross the river without the assistance of riders. After crossing the Inylchek, the expedition caravan stopped at the edge of a sparse forest at the foot of the mountain.

This was the highest peak of the Inylchektau Range (5,897 m), unmarked on the map and unnamed. Pogrebetsky decided to name it Nansen Peak in honor of the famous polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen. The campsite was windless and teeming with game.

After a two-day rest, Pogrebetsky left Golovin's party at the camp and headed with the caravan to the Inylchek Glacier. As they ascended the glacier, the grass and sparse shrubs disappeared, but smooth granite cliffs - sheepsheads, polished boulders, and endless, enormous moraines - became more common.

There are many glaciers in the Central Tien Shan, some of them very large. But what Pogrebetsky saw exceeded all his expectations. Before him lay one of the world's largest glaciers (Inylchek is 60 kilometers long and covers 823 square kilometers).

The drifts of sand, rock, and rubble covering the glacier gave it the appearance of a gloomy, rocky desert. The heavily laden horses trudged slowly across it, often slipping and falling. On the third day after leaving base camp, Pogrebetsky saw a steep, narrow ridge running east to west, its entire mass cutting deep into the ice, bisecting the Inylchek Glacier into two branches - northern and southern.

Pogrebetsky named this ridge "Battleship," a name that has remained to this day. As the expedition caravan approached the ridge, a question arose: which part of the Inylchek Glacier should they follow - the northern or the southern? Shimansky, Bagmut, Zauberer, and old Nabokov walked ahead of the caravan.

They marked the route with red ribbons or flags and, if necessary, cut steps - "troughs" - for the horses. But Pogrebetsky soon realized that this tactic was also unsuitable for the conditions of the Inylchek. It was then decided to send the horses down and split into two groups: one would advance up the northern branch of the Inylchek, the other along the southern.

This solution would allow them to scout the approaches to Khan Tengri from both directions and determine which route was best. Old Nabokov and the horsemen with Nurgadzha set off with the horses down to the base camp. Shimansky, Bagmut, Kolyada, and Redak were to proceed up the Southern Inylchek, while Pogrebetsky, Zauberer, cameraman Laziyev, Fatima Tairova, Nabokov's son Mikhail, and another caravan driver would travel up the Northern Inylchek, which Mysovsky's group had approached a few days earlier.

The most difficult part of the trek had begun. The mountain slopes were so steep that their very appearance was dizzying. They had to cut steps into the slopes, hammer pitons into the ice, and hang ropes. Ahead lay a chaotic jumble of rocks, ice, and moraine embankments.

But what lay beyond the moraines? Perhaps the lake Merzbacher had mentioned. But twenty-six years had passed since then. It might no longer exist. If they managed to reach it, the mystery of the mountains marked as a "blank spot" on geographic maps would be solved.

The next morning, the lead detachment of the expedition reached the lake. It lay below, surrounded by a semicircle of sheer cliffs, much as Pogrebetsky had imagined it from Merzbacher's descriptions and Nabokov's stories (later, M. T. Pogrebetsky named this lake after Merzbacher).

Ice chunks floated in the clear water. Approaching the lake, Pogrebetsky realized that the route to Khan Tengri via Northern Inylchek, while shorter, was not the easiest. It turned out that the steep cliffs that formed a semicircle around the lake were inaccessible.

Pogrebetsky decided to cross the lake by moving across the ice floes. They walked for three hours until their path was blocked by ice holes. They began to navigate around them, but a new obstacle arose - huge ice floes floating in the water. "How many times," Pogrebetsky later recalled, "did we waste a great deal of time and effort, and, reaching an ice wall or a wide thawed patch, were forced to turn back and start over."

And one day, when it seemed they'd already bypassed the ice walls and thawed patches, and the spurs of Khan-Tengri were about to appear above, to the north, everyone suddenly realized they couldn't go any further. Ahead, from south to north, stretched a wide, clear, ice-free stretch of water...

"The famous Merzbacher couldn't cross the lake and go around it either," Pogrebetsky tried to console himself. Twilight fell unnoticed. Mikhail Nabokov stumbled and fell into the water, then the same happened to Pogrebetsky and Zauberer. Their clothes were soaked, and water splashed in their boots.

But returning in the fog wasn't so easy. There was nowhere to stand and wait for help. Meanwhile, night had set in. Clouds rolled in, and snow began to fall. Soaking wet, half-frozen, the travelers searched for a way across the lake until late at night. Their strength was ebbing, and suddenly they saw a dim light.

"Our guys are signaling!" Zauberer cried.

Laziyev and Fatima were waiting for them on the glacier's moraine ridge. Having escaped the icy embrace, Pogrebetsky was now certain that they would not be able to reach Khan-Tengri across the lake. Then he decided to catch up with Shimansky's group and head for South Inylchek.

Unlike its northern counterpart, South Inylchek did not have a continuous moraine cover. Moraine ridges alternated with patches of clear ice on the glacier, and only where the glacier bed formed high rocky ledges was the icefall visible, with its intricate labyrinth of crevasses and ice floes.

As he climbed South Inylchek, Pogrebetsky noticed a dome-shaped peak, and to the right of it, on the other side of the glacier, granite cliffs, similar to each other, with a large glacier between them. The dome-shaped peak (later determined to be 5,860 meters high) was named after Grigory Ivanovich Petrovsky, then chairman of the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee, and the large glacier flowing into Inylchek was named "Komsomolets."

Beyond Petrovsky's peak, the travelers saw seven other, equally high, unnamed peaks. For three days, Pogrebetsky's group traveled along South Inylchek, and for three days the peaks steadily advanced. The highest was the seventh, and beyond it, Pogrebetsky assumed, Khan Tengri lay to the west.

Just when it seemed their destination was within reach, a gusty wind blew up, lifting clouds of snow from the steep slopes and swirling them across the glacier. A drifting snowstorm raged, so strong that further travel was impossible. They couldn't pitch a tent either.

They were forced to sit out the night in their sleeping bags. The blizzard raged all night, and when the wind died down in the morning, Pogrebetsky and his companions saw that the mountains and glaciers were completely covered in snow. Seven days had passed on the glacier, and three days would be needed for the return journey.

A total of ten days, Pogrebetsky reasoned, and Golovin, who was waiting for him with his detachment at Nansen Peak, would only have to wait ten days. What to do? Should they go to Khan Tengri? But what if there was solid cloud cover there? And suddenly, as if by magic, a sharp wind burst from a side gorge.

The clouds cleared, and a white cone appeared in the blue sky like a ghost. "Before us," wrote Pogrebetsky, "stands a monolithic pyramid, carved from a single piece of marble and seemingly pressed into the icy pedestal... From here, the summit of Khan-Tengri appears wider and lower than from the vantage points from which we observed it previously.

This is understandable: we are so close that perspective is distorted. Moreover, the size of the colossus before us is greatly diminished by the black cliff of the neighboring peak..." On October 2, having joined forces, both expedition groups turned back.

A day later, someone spotted a figure below at the glacier's tongue. It was Nurgadzh. Pogrebetsky took a note from Nurgadzh from Golovin.

"Please do not delay for another hour," wrote Golovin, "as, due to the current circumstances, I cannot remain here for an extra minute." On September 28th, we were attacked by Dzhantay's band, fifty men strong. The band was repelled. Today, September 31st, the band repeated the attack and was again repelled. I suspect that in the very near future the band will attack again, but with a stronger force. I await your speedy return...

There was no time to waste. Having loaded the horses driven by Nurgadzha, Pogrebetsky immediately set out for the base camp at the foot of Nansen Peak. There, he joined Golovin's detachment and, together, descended into the Sarydzhaz valley.

"It's a pity, of course, that we were unable to fulfill our intention and reach Khan Tengri again," wrote M. T. Pogrebetsky in his book, "In the Heart of the Celestial Mountains." "But we are leaving the Tien Shan not without results. The route along the Southern Inylchek to Khan Tengri and the conditions for traveling through the most inaccessible part."

"The Celestial Mountains have been explored..."

Authority:

I.E. Vetrov. Series "Remarkable Geographers and Travelers." First to Khan-Tengri. Travels of M.T. Pogrebetsky. Mysl Publishing House. Moscow, 1971.

http://www.mountain.ru/article/mainarticle.php?article_id=5726&code=1