You are here

First mentions of Burana.

Medieval settlements in Kyrgyzstan.

“In (the district of) Chu (or Ju; in the English text it is often distorted as Juz. - M.M.) in one place there are traces of an abandoned city. Its minarets, domed structures and madrassas have been preserved in some places. Since no one knows the name of that city, the Mongols called it “Munora”.

V.V. Velyaminov-Zernov. “Research on Kasimov kings and princes”. Translations into Persian and Jagatai languages of text of article from “Ta’rikh-i Rashidi”. 1843.

Medieval minarets in north and south of Kyrgyzstan.

The term miiaret, which was widely used in European circles, comes from the Arabic miyar (a place where something is lit - a lantern, a lighthouse) or minara (a watchtower, a pillar, a minaret of a mosque). For the first time, such an interpretation of the term "burana" was given by N. F. Petrovsky in his article "What are the ancient ruins near Tokmak with a tower known as Burana" from the words of the teacher of the Tokmak Russian-native school V. P. Rovnyagin. (Turkestan Vedomosti, Tashkent, 1894, No. 25).

His article was then reprinted under the title "The Burana Tower near Tokmak". ZVORAO, Vol. VIII. 1894, p. 351 - 354. In the latter meaning, with local pronunciation among Tajiks and Uzbeks - meiare, and among some Central Asian peoples of Turkic origin - menar.

Among the local population living in the former northern Kyrgyz region of Jetysu (Semirechye), and in modern scientific literature, this word is used in the form of burana, which is certainly explained by the linguistic feature of the Kyrgyz language.

The minaret owes its name to the throwing of various convicted persons from it in former times by order of the emirs, which is denied by many authors in European and Russian literature, but confirmed by a number of written sources. Thus, at the end of the XVIIth century, one Bukhara acrobat, using brackets he invented, managed to climb the outer surface of the minaret to its top.

The presence of such a master in the capital seemed unsafe. In the interests of the integrity of the treasury and the protection of private property, the inventor was thrown from the minaret by order of the then ruler Subhan Kuli Khan (1680 - 1701).

Many Europeans who visited Bukhara (Borne, Skyler, Schwartz, etc.) mention the throwing of various criminals. In 1871, this was done, among other things, to the head of the Baba-khnom gang of robbers. The last time the same fate befell a thief who stole a large sum of money from a rich Bukharan merchant.

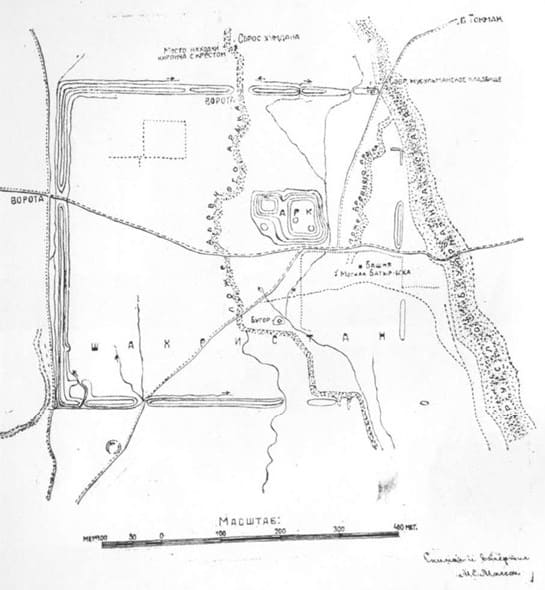

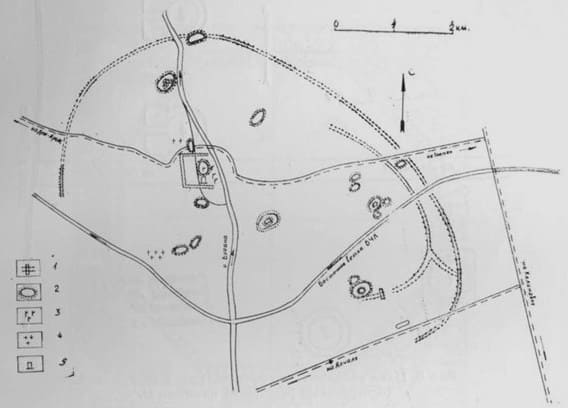

In this form, this term became the geographical name of an unnamed medieval settlement located in the southeastern part of the Chui Valley, at the foot of the Kirghiz Ala-Too ridge (or Ala-Tau, former Alexander ridge), 11 kilometers "southwest of Tokmak.

It also became the proper name for the ruins of a large medieval minaret located inside this settlement and for the bed of a mountain river flowing around the settlement from the eastern side and being the left tributary of the Chu River. In some works of Arab authors of the IXth - Xth centuries, who wrote about Central Asia, there are many names of various settlements and even significant cities that existed at that time in Semirechye.

After the Xth century, the information of Muslim writers about the Chu Valley becomes more vague, the names of the places are given without precise indications of their relative positions, the distances between them! Their life was mainly interrupted soon after the Mongol conquest, to a large extent and in connection with the change of population, the former names of numerous deserted ruins were firmly forgotten.

Their life was mainly interrupted soon after the Mongol conquest, to a large extent and in connection with the change of population, the former names of numerous deserted ruins were firmly forgotten.

At present, it is not easy to establish which archaeological site a particular name that has come down to us in written sources refers to. The desire to get answers to the questions that arose - who created, when and why was this or that ancient monument built? - gave rise to many legends among the people.

This also affected the Burana settlement with the remains of its huge minaret. Already in 1860, M. I. Venyukov, who was traveling through the Central Asian outskirts of Russia, wrote that at that time the Kirghiz (Kara-Kirghiz) revered some monuments of the peoples who previously lived on their lands.

In particular, he briefly noted that the high "pillar" located near Tokmak, allegedly made of adobe, was especially revered by the Kirghiz. According to legend, some kind of the khan's daughter, placed there by her father, who was hopelessly trying to protect his child from the predicted death from the bite of "phalanges or other insects."

Later, from the words of the Kirghiz and Russian old-timers who settled in Tokmak, a number of authors recorded the content of this legend in several versions. According to one of them, in ancient times (without specifying the time), a certain local khan was predicted that his beloved daughter would die upon reaching her maiden prime from the bite of a black poisonous karakurt spider (Lethrodoctes tredacimguttatus), which was found in large quantities in the Tokmak region.

In order to create an environment for his daughter that would exclude the possibility of the prediction coming true, the father ordered a tower to be built for her from burnt bricks, in the very top room of which she spent her days and nights in despair.

As a precaution, servants were stationed from the very entrance to the minaret to the top of the internal staircase, handing over everything necessary to the khan's daughter from hand to hand after a thorough check. But the inevitable could not be averted by any measures.

At the predicted time, the girl was struck down by two small fatal pricks from the poisonous jaws of a black widow spider, accidentally brought in a basket with bunches of black grapes. According to other versions, the khan built the tower for his only surviving heir to power - his beloved youngest son.

However, he also died (following his older brothers) from the bite of a black widow, which a careless servant accidentally brought into the upper room of the minaret on a large platter of fruit. In the content of all the variants of the given legend, bearing signs of book influences, except for the mention of the karakurt, there was nothing specific to Semirechye.

A number of Russian authors, retelling the content of this legend, until recently groundlessly attributed the fatal bite to a representative of a family of some insects without an exact indication of their species or to a non-poisonous arachnid insect - a phalanx.

Similar plots are common in Persia, the Caucasus and the west - to the coast of the Sea of Marmara (for example, in the legend of the Mandra castle near the Bosphorus), and in Central Asia similar legends are associated with a number of archaeological monuments located in hard-to-reach mountainous regions.

In historical terms (in the sense of reflecting in the Kyrgyz legend the time of the construction of the Burana minaret), the mention of the builder of the tower by the name of Arslan Khan is of some interest. V. V. Bartold drew attention to this in the last century as a typical nickname for some rulers from the Karahapid dynasty.

At the same time, the Russian consul in Kashgar, N. F. Petrovsky, pointed out that in this case we are unlikely to have an exact echo of a past event, since among the Kirghiz and Kazakhs the names Kyzyl-Arslan Khan and Sattuk Bogra Khan are so popular that they are credited with the construction of a number of buildings in various parts of the northern part of Central Asia and Kashgar.

The earliest dated mention of the ruins of medieval cities in the Chu or Chui River valley is still, apparently, the news of "Ta'rikh-i Rashidi", dating back to the XVIth century. Information about the ruins of the city of Monora belongs to the author of this work - Muhammad Haidar-Mirza Guragani, who saw the ruins of this ancient monument.

The information he reported on this matter was noted by V. V. Velyaminov-Zernov in the middle of the last century. In a note to the IInd volume of his major work, “A Study of the Kasimov Tsars and Tsareviches,” he provided the text of the article from “Ta’rikh-i Rashidi” in Persian and Jagatai.

The first was given according to a manuscript from St. Petersburg University, written with errors in 1843. The text in Jagatai was based on an incomplete handwritten translation of the work of Muhammad Haidar Guragani in the Kashgar dialect, made by Muhammad Sadyk Kashgari in the XVIIIth century.

In addition, the academician also provided a Russian translation of information about the Burana settlement. Later, in 1897. V. V. Bartold gave a Russian translation of the same place from the Persian text with corrections of minor inaccuracies made by V. V. Velyaminov-Zernov.

There is an English edition: The Tarikh-i Rashidi of Mirza Muhammad Haidar, Duglat-A History of the Moghuls of Central Asia. - An English version, edited, with commentary, ntes and map by N. Elias, H. M. Consul-General for Khorasan and Sistan. The translation by E. Denison Ross. n-don, 1895.

The bibliographic rarity of the listed publications and the information they contain about the Burana settlement, which is of considerable interest, given the small number of original manuscript copies, make it useful to provide a corresponding unique text about the archaeological site we are studying.

"In (the district) of Chu (or Dju; in the English text it is often distorted as Djuz. - M. M.) in one place there are traces of an abandoned city. Its minarets, domed structures and madrassas have been preserved in some places. Since no one knows the name of that city, the Mongols called it "Munora".

In addition, there is a domed structure (apparently a domed mausoleum. - M.M.) and (there must be in it. - M.M.) a stone slab on which the inscription is carved in Easter script the most glorious imam and the immutable, the most perfect sheikh, who embraced both the contemplative and the experimental sciences, an expert in both the branches and the foundations of jurisprudence, Imam Muhammad-faqih Balasagunsky.

May the tree of his communication with God never cease to blossom on his grave and may the gaze of worthy men be forever directed to him! He died in 711 AH (1311 - 1312 AD). This was written by the blacksmith Omar-Khoja." Chu is one of the areas of Moghulistan, stretching for one month's journey.

There were many cities like this (there). Having brought this news to the publication of the 2nd volume of his “Research on the Kasimov Tsars and Tsareviches” at the end of 1864, despite his great erudition at that time in matters of the Kokand possessions, V. V. Velyaminov-Zernov could not compare the description of the Munora settlement with any Central Asian ruins.

Apparently, he was not only unaware of the Burana settlement, but generally of the ruins of cities in the Chu River valley. This can be judged by his own words at the end of the note he cited: “For ruins found within the boundaries of the current Kokand Khanate in places adjacent to Turkestan, see my article “Information on the Kokand Khanate” in the “Bulletin of the Russian Geographical Society”, 1856, volume XVIII. Research and materials, p. 140 (p. 164). However, there are no mentions of any archaeological ruins in the area of the Chu River.

If in the first half of the XIXth century the Russians did receive fragmentary oral information about Burana, then this was almost not reflected in literature. In essence, the exception is a short message from Voronin and Nifantyev that once, not far from Tokmak, on the ruins of an ancient tower called Munara, a jug with a copper coin was found.

This is explained by the location of the indicated point: the busier trade route between Russia at that time and the possessions of the Kokand Khanate (as well as various routes through the Chu River valley) usually ran west of Tokmak. In fact, the turning point in this regard was the active military actions between the aforementioned states, which began in 1860, when on August 26, Russian troops first entered the Tokmak fortification, and on September 4, the Kokand fortress of Pishpek was taken.

Although soon after that, the Russians left the occupied territory for some time and retreated to Kastek, but already in 1861 the above-mentioned work of M. I. Venyukov appeared, which spoke about the Burana tower and the legend associated with it, which was common among the Kirghiz.

In 1860, in the battle with the Russians at Uzun-Agach, on October 21, Tyurya Khodja, the son of Znaaddin Khodja Andizhan, took part on the side of the Kokand troops. In his work on the history of the Kokand Khanate, completed in 1289 (1864 - 1865), he described the campaign to Uzun-Agach, mentioning a large city destroyed in the Chui district in the past, among the ruins of which a high ancient minaret was preserved.

The impression from the view of the tower even distracted the author for a while from a consistent presentation of the course of events. In 1862, the Chui Valley finally became part of Russia. Soon, since 1864, the Russian fortification of Tokmak became a district center for some time. In addition to a permanent garrison, several dozen families of Russian peasant settlers were housed in it.

At the same time, a gradual influx of sedentary Uzbek population began. The former fortification (or as the settlers called it - "town") quickly began to grow into a small town. This circumstance initially created a certain threat to the ruins of the Burana settlement.

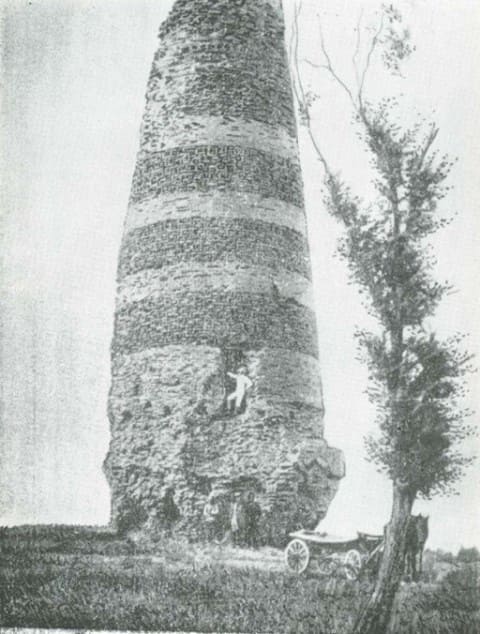

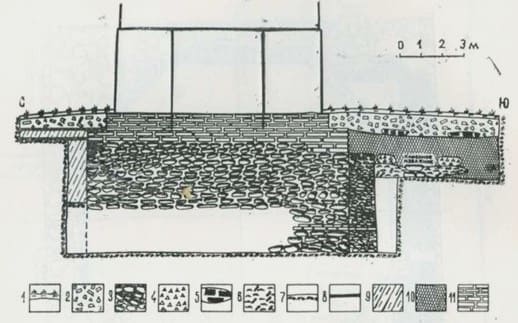

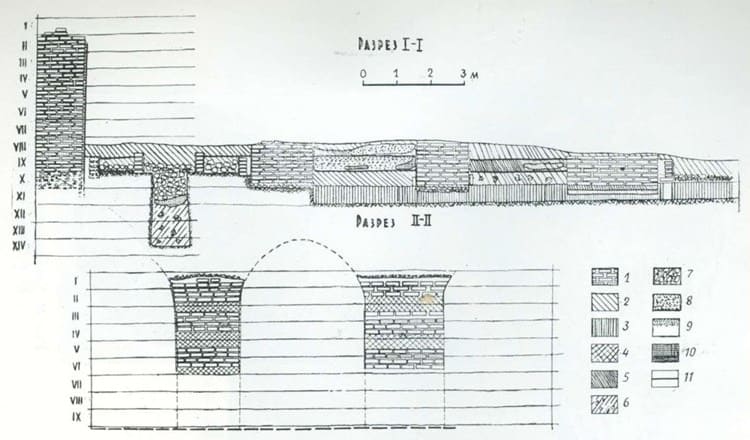

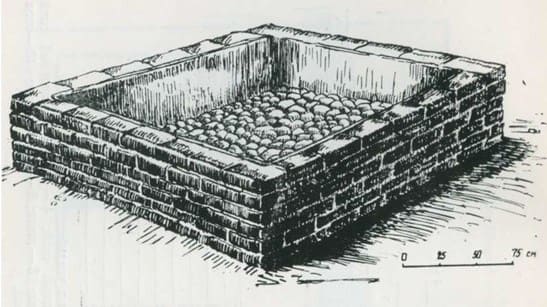

The growing need for building material began to be intensively satisfied by the new settlers at the expense of ancient burnt bricks, which were collected not only from the surface of the settlement, but were also mined during the dismantling of the remains of former medieval buildings that had survived at that time.

The bricks from the settlement were mainly used for laying out stoves, installing indoor floor drains (khanyk) and other household needs. Among the monuments of local antiquity, the attention of the inhabitants of old Tokmak was attracted by various pagan burials, among which local residents distinguished "santashi", "yugantashi" and "mugtashi".

Interest in them was heightened every time information was received about new finds of gold and silver items by the Kyrgyz in the ancient graves they were digging up. However, even at that time, a few amateur local historians paid tribute to the amazing Burana minaret.

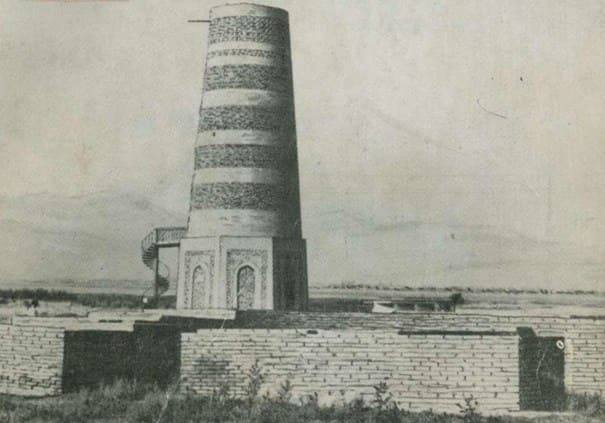

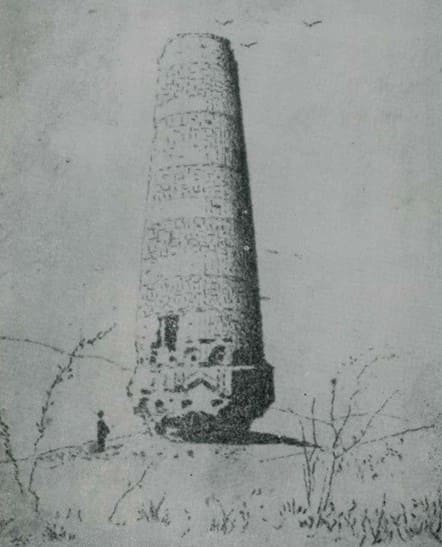

They did their best to promote the need to preserve it, since before their eyes the lower parts of this monument were gradually being dismantled. One cannot help but note the positive registration role that some artists played at that time. As V. D. Goryacheva established on the basis of archival data, during the military actions of 1863 - 1864, Uspensky, a participant in the then campaigns, in his album of drawings next to the ruins the huge Burana tower placed an image of a small minaret that was still standing nearby at that time.

In 1869, the Burana tower was sketched by the outstanding Russian artist V. V. Vereshchagin. The lack of not only proper protection of numerous historical monuments in Semirechye, but even their preliminary study in the historical aspect caused a growing protest among the progressive Tashkent public.

When it became clear that a special Swedish archaeological expedition intended to visit the city of Tashkent and some areas of the Turkestan region at the end of 1876, these sentiments were expressed in the local press, where local lovers of antiquity were accused of indifference to the monuments of Dzhetysu.

In practice, some administrative orders carried out in the order of preparatory measures for holding the IV Archaeological Congress in Russia at the end of the summer of 1877 were of much greater benefit. At the beginning of the specified year, the Turkestan Governor-General K. P. von Kaufman proposed to the military governor of the Semirechye region to deliver to Tashkent materials related to the archeology of Jetysu and Kulja.

He, in turn, addressed the same to the persons subordinate to him. The unpreparedness of officials to perform such tasks, the meager supply of previously accumulated relevant materials and a number of other objective reasons made it difficult to complete the received task, which required a description of the "archaeological" objects (architectural monuments, burial mounds, rock inscriptions and images) preserved on the surface.

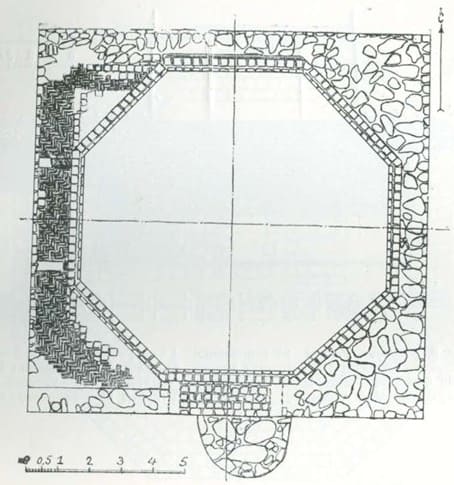

In addition, it was proposed to record folk legends about them and collect archaeological finds. Despite the indicated difficulties, it was possible to obtain some descriptions, plans, photographs and sketches. At the same time, a special map of the territory subordinate to the Semirechye governor was drawn up with the location of all registered objects marked on it.

Among the ancient monuments noted was the ancient settlement of Burana, located "15 versts" from Tokmak, called "Turt-kala", as well as the tower located on it. Were legends written about the latter from the words of local Sarts and Kirghiz? Plans and sketches were not presented.

The information about Burana received from the Turkestan Governor-General was read by V.D. Smirnov at a meeting of the Department of Eastern Antiquities of the IV Archaeological Congress in Russia, which took place in Kazan on August 8, 1877.

Several comments were made regarding the legends about the "Burana Tower". The message itself was not published.

Authority, photographs and schemes by:

M.E. Masson. V.D. Goryacheva. "Burana. History of study of settlement and its architectural monuments". Academy of Sciences of Kirghiz SSR. Institute of History. Ilim Publishing House. Frunze, 1985.